Trump’s re-election chances depend a lot on voters’ assessment of his COVID-19 management. However, polls indicate his handling of the virus is regarded as highly problematic by many. Why has Trump’s populist administration failed so comprehensively at addressing this critical issue, and instead relied on a campaign of deflection and denial?

An Overview

The death toll from Covid-19 continues to grow relentlessly in the United States (US). More than 207,000 Americans have now died from this pandemic. That is the highest total for any country in the world and accounts for 20% of all Covid-19 related deaths.

Yet this grim situation and the prospect of many more American deaths has only served to further polarise an already deeply divided society.

In a tumultuous presidential debate last week at Cleveland, Ohio, President Trump showed no signs of reconsidering his Government’s handling of the Covid-19 crisis. Further, Mr Trump is now confirmed as having the virus along with at least ten others who attended what has been described as a “super spreader” event at the White House to mark the announcement of his nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Responding to Senator Joe Biden’s claim Mr Trump had deliberately deceived the American people on the seriousness of the disease and still did not have a plan for dealing with it, Mr Trump insisted “we have done a phenomenal job with respect to Covid-19” and had saved the lives of “millions of people” in America.

It is clear that Mr Trump’s re-election chances will depend, at least in part, on whether enough voters accept that claim.

The COVID-19 Crisis

The COVID-19 global pandemic is only the latest in a long line of preventable catastrophes and disasters.

As we know, since late November 2019, the COVID-19 virus has spread from the Chinese city of Wuhan to more than 180 countries and territories, affecting every continent except Antarctica.

On 30 January, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a “public health emergency of international concern” and advised countries to respond to the virus with a multifaceted strategy of testing, contact tracing, isolation, and treatment.

Deeply concerned by the alarming levels of spread and severity, the WHO classified COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11 March.

To date, there have been 999,298 deaths worldwide from COVID-19 and 33,224,222 confirmed cases worldwide (Bloomberg, 29 Sept. 2020).

Trump’s Response to COVID-19 crisis

For four months after the first Covid-19 outbreak was detected, the Trump administration publicly and repeatedly reassured Americans they had little to worry about.

However, there was no shortage of warnings to the Trump administration about the potential seriousness of the situation.

In late November 2019, US intelligence officials warned that the coronavirus spreading at Wuhan in the Hubei region could become a “cataclysmic event”.

On January 30, Peter Navarro, Donald Trump’s senior trade adviser, wrote a memo warning that the coronavirus could create a pandemic. In late February, he wrote a second memo saying the virus could kill up to two million Americans.

But Trump spent much of February publicly downplaying the threat of Covid-19. “We think we have it very well under control,” the President said.

Trump publicly thanked President Xi Jinping on 24 January for his country’s “efforts and transparency” in dealing with Covid-19 and said “it will all work well.”

Trump said the number of cases in the US would soon be “down to zero” and called concerns about the virus a “hoax”.

On 13 February, President Trump praised China for handling the outbreak of COVID-19 in a “professional manner” and expressed the hope that this health problem “is going to be resolved”.

Even as late as March 6, the US President was favourably comparing Covid-19 to the seasonal flu.

The US was very slow to develop mass testing. Instead of using a test developed by the World Health Organisation, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) opted to develop its own test.

However, it was only on March 17 that Trump publicly conceded Covid-19 was a highly contagious “invisible enemy” and necessitated robust social distancing guidelines.

Nevertheless, President Trump’s messaging – he has continued to speak of America getting backing to work and expressed public scepticism in relation to scientific advice concerning the use of lockdowns and the wearing of face masks to help slow transmission of the virus – has complicated US efforts to present a coherent response to the pandemic.

Explaining the Trump Response

So why has Trump administration performed so poorly in dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic?

A substantial part of the answer to that question lies in the fact that Trump is a populist leader.

Populism embraces an ideology which considers society to be divided between ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite’, and contends the ‘will of the people’ requires the promotion of mono-culturalism, national self-interest, closed borders, and traditionalism.

Populists who have made it into power like Trump have presented themselves as the authentic voice of the people and harnessed anger, grievances, nationalism, and racism to win political support.

But the operational code of Trump’s populism has collided with the cold realities of Covid-19 – now quite literally with his own infection.

First, populist leaders like Trump have a view of the world that is compartmentalised into nation-states and their different populations. But Covid-19 recognises no border and makes no distinction between human beings.

Second, and not unrelated, populist leaders distrust international institutions and believe in the exceptionalism of their sovereign state. It is no coincidence that Trump largely ignored dire warnings from the WHO until March and then blamed the mishandling of the pandemic.

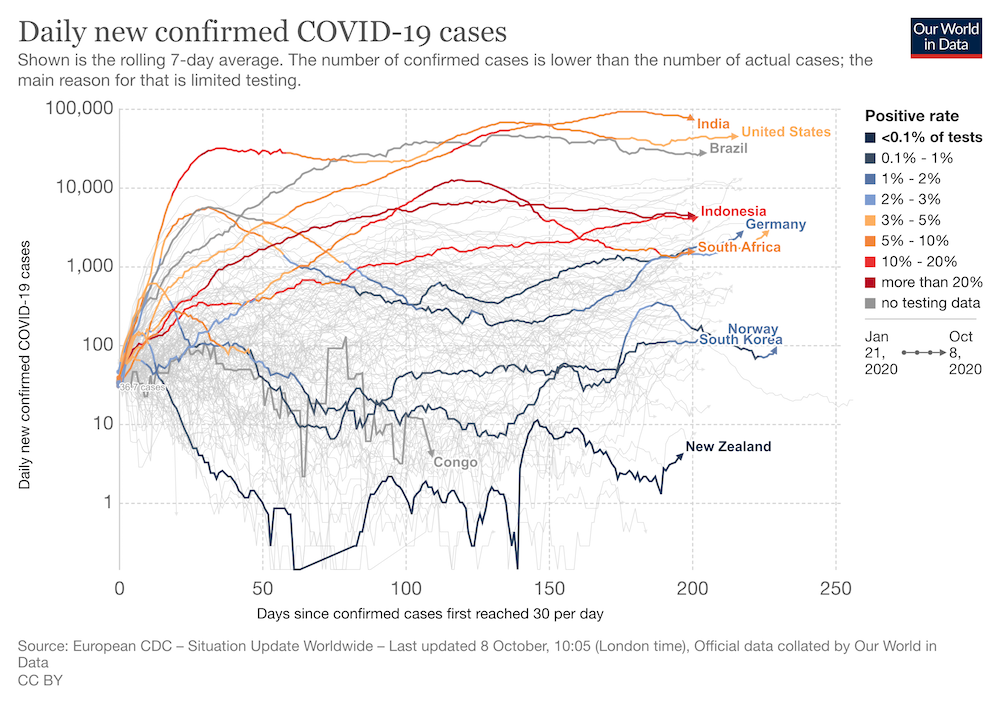

Furthermore, Trump showed little willingness to learn from the positive efforts of other states like South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Germany, New Zealand, and even his favourite scapegoat – China, in dealing with the threat of Covid-19.

Third, populist leaders pride themselves on their own common sense and are dismissive about the knowledge of experts in policy-making unless the experts are sympathetic to their political agenda.

As related, President Trump has repeatedly contradicted Dr Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Dr Deborah Birx, the White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator.

In short, the big problem for the Trump administration is that Covid-19 does not play by the political rules of populist leaders but rather by the rules of science and objective reality.

Trump privately acknowledged this in a taped interview with Bob Woodward, the Washington Post journalist, in February when he made it clear that he fully recognised the deadly danger represented by Covid-19.

Nevertheless, Trump would continue to publicly downplay the threat of the virus for another month. He told Woodward he was reluctant to share his private concerns about Covid-19 because he did not want to panic the American people!

Given that Trump had previously demonstrated few concerns about panicking the American peoples, that explanation can be taken with a large pinch of salt.

The reason why Trump remained in public denial about the dangers presented by Covid-19 for so long was that it drove a coach and horses through his populist ‘America First’ political narrative and that he hoped to limit the damage to the US economy.

How will Trump’s handling of Covid-19 affect the US election?

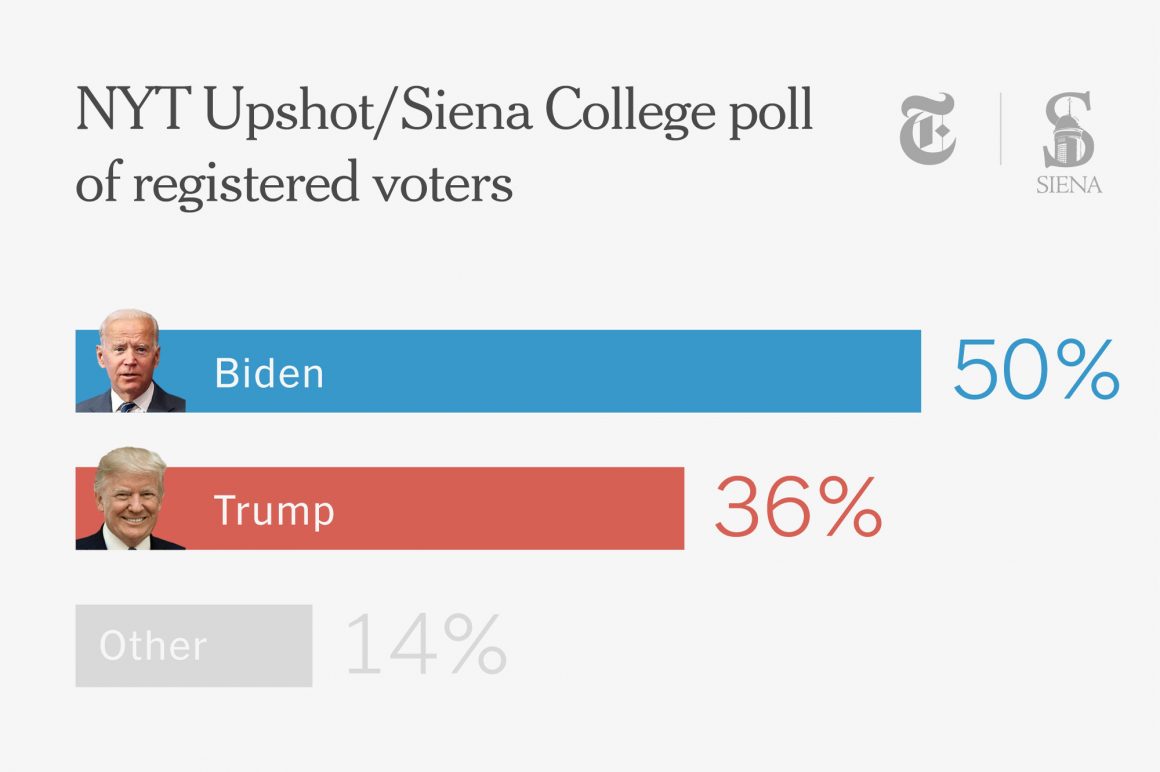

Covid-19 will be the central issue in the November presidential election. According to a recent ABC News poll, Trump’s approval for his handling of COVID-19 stands at 35% in the new survey, which was conducted by Ipsos in partnership with ABC News using Ipsos’ Knowledge Panel, compared to 65% who disapprove. This marks the fourth straight poll with Trump’s COVID response approval hovering in the low-to-mid 30s since early July.

President Trump’s election strategy has been one of deflection and denial that he holds primary responsibility for America’s COVID-19 crisis. The deflection part was in evidence during the shambolic first presidential debate. COVID-19 was described as “the China virus” and that the rest of the world, including America, would not be facing this problem if Beijing had been more forthcoming at the beginning of the outbreak in Wuhan.

The denial element was also on display during the debate in Cleveland. By putting a very positive spin on his administration’s response to COVID-19 – Trump has said millions of Americans would have died if Joe Biden had been in the White House – the president has attempted to redefine the significance of America’s current death tally so that he has done well, not badly, in difficult circumstances.

Claims by Trump that an American vaccine against Covid-19 will probably be developed before the November election are also part and parcel of the campaign effort to de-centre the pandemic as a central election issue.

However, there is little evidence that the deflection and denial strategy is working. The fact that President Trump and the First Lady have now tested positive for Covid-19 would seem to be a symbolic indication that the Trump White House has largely lost control of the process of shaping the terms of the 2020 election debate.

Joe Biden is leading President Trump in the national polls for the presidential election, but it is a handful of swing states that will decide which candidate wins the electoral college and the current evidence here does not look encouraging for Trump in these heavily targeted states.

At present, Biden is ahead in Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, North Carolina, Arizona, Wisconsin but is narrowly behind Trump in Iowa.

Such polling evidence currently suggests that Trump is likely to pay a big political price for his administration’s slow and often chaotic response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Robert G. Patman is a Professor of International Relations at the University of Otago

Comment here on ScoopCitizen