Comparing New Zealand’s elimination approach to the Covid-19 pandemic with the alternatives, the upsides overwhelmingly outweigh the downsides. However, there is much more our ‘liberal technocrat’ Government could be doing to better manage the Covid-19 crisis, and make our system more resilient in the face of future public health emergencies.

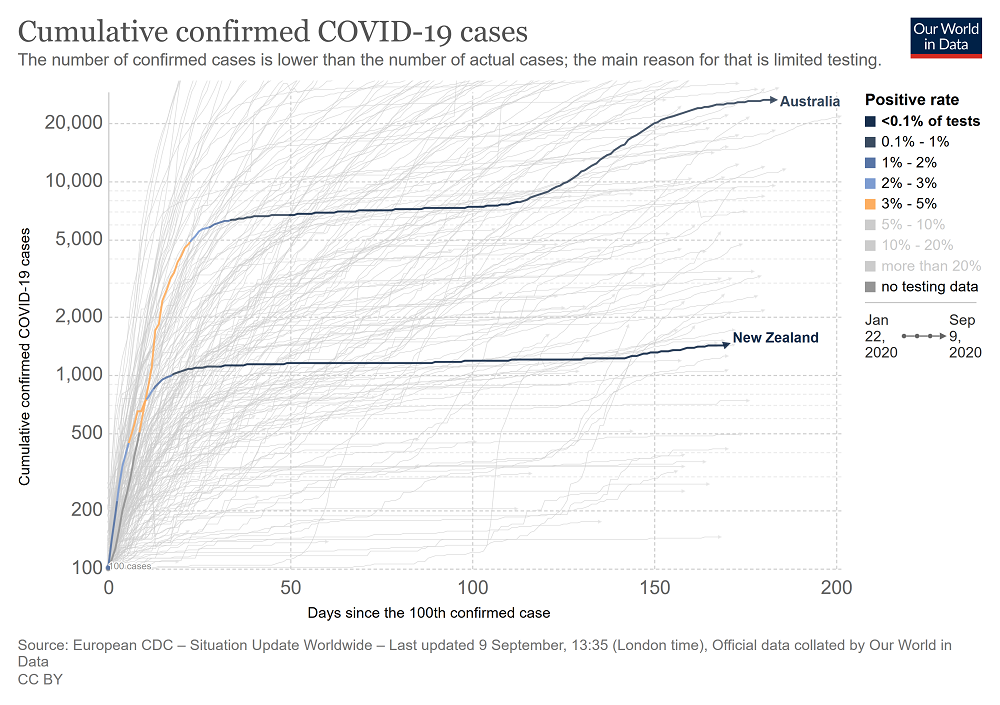

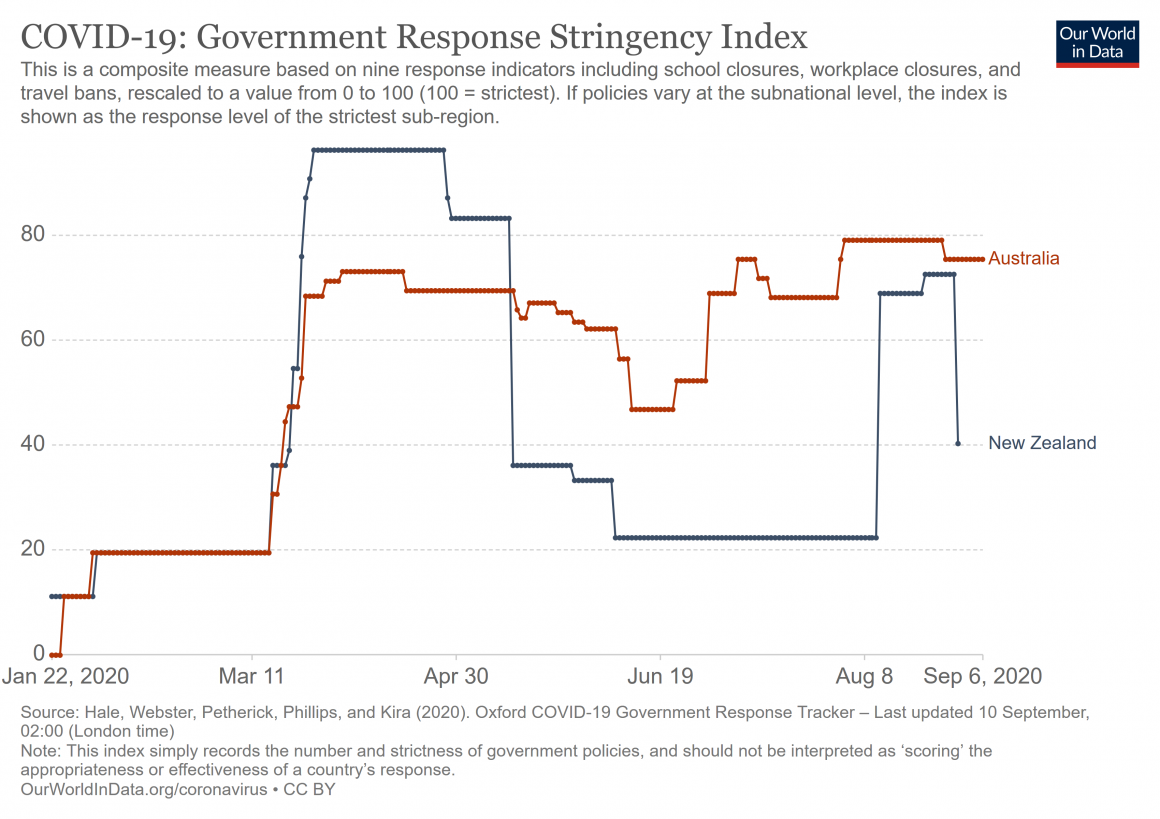

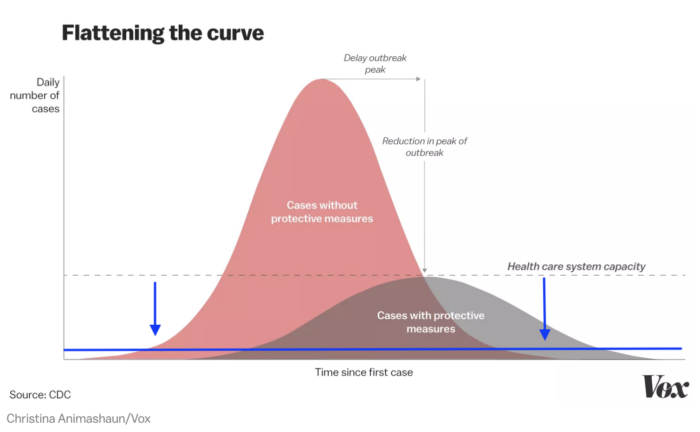

Perspective is critical when considering New Zealand’s approach to the devastating Covid-19 pandemic. The Government has pursued a strategy of elimination (no community transmission) rather than that pursued by many other countries, including Australia, who have pursued containment (also called suppression).

The best statistical assessment of New Zealand’s performance internationally is provided by World Health Organisation data on deaths per 1 million people (30 December-23 August) which is updated weekly. The data confirms that the upside overwhelmingly outweighs the downside.

The upside

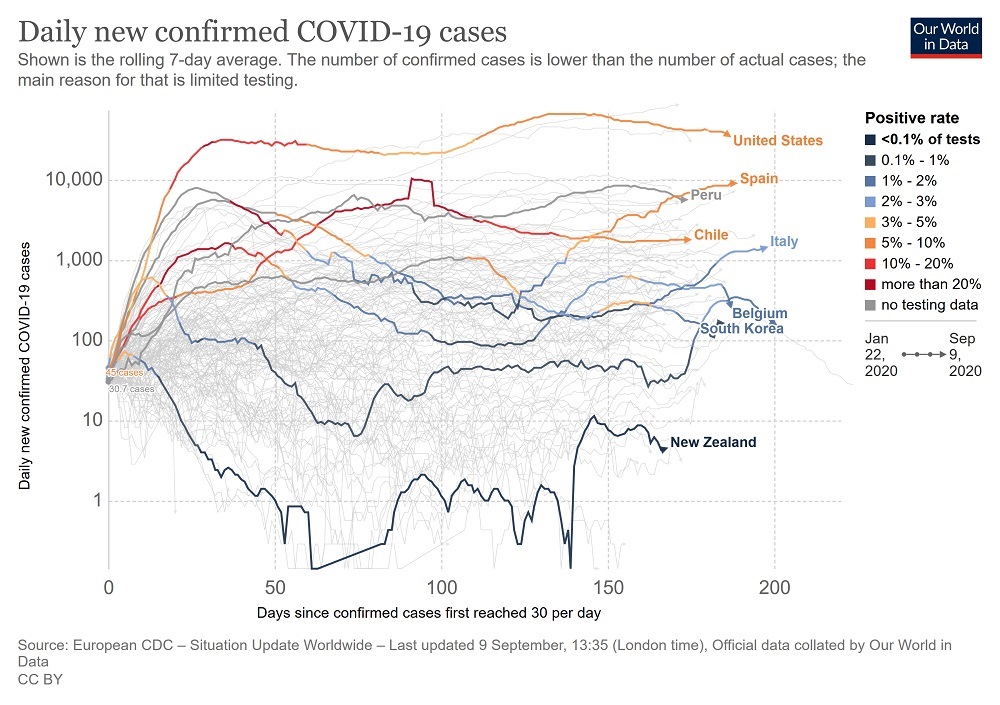

Excluding microstates, the 9 worst performing countries were Belgium (862 deaths per million), Peru (726), Spain (617), United Kingdom (610), Italy (586), Sweden (575), Chile (565), Brazil (533), and United States (526). All focussed on containment although Sweden mixed containment with its ill-fated ‘herd immunity’. Only Peru experienced a relatively improved mortality rate over the previous week. All others saw their rates further deteriorate with Brazil having the biggest jump.

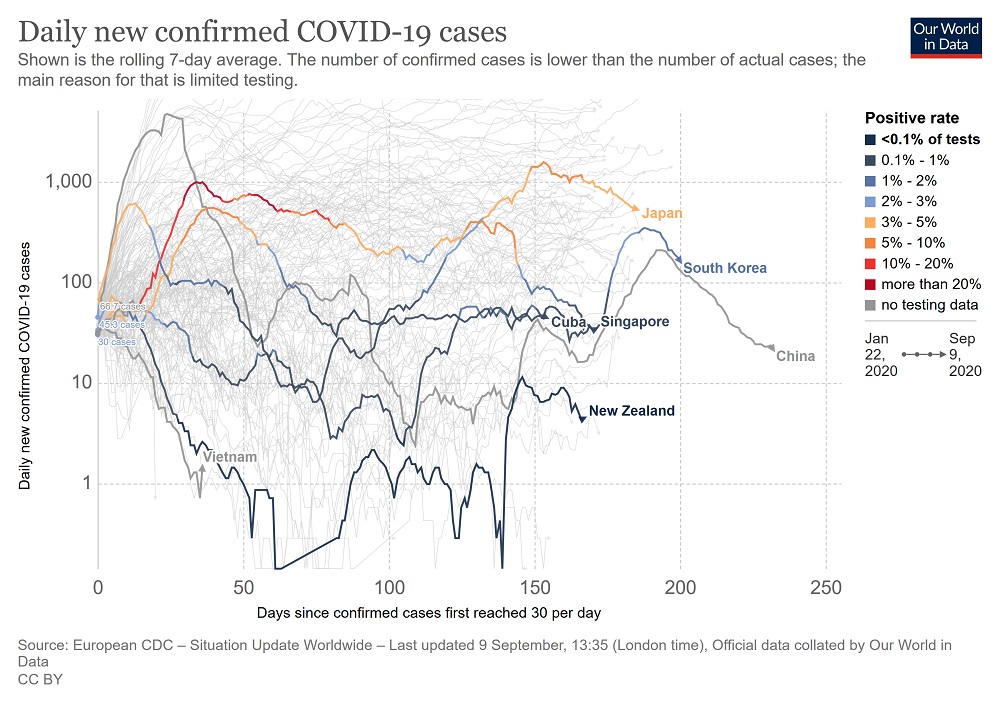

By contrast, New Zealand’s mortality rate is 5 per 1 million (the same as Singapore) – over 100 times better than these 9 countries. Very few countries have done better with the main ones being Vietnam (less than 1) and China (3). Among the select few very good performers are South Korea (6), Cuba (8) and Japan (9).

New Zealand’s success also meant that we are better placed to handle subsequent outbreaks. The Government’s response to the new Auckland cluster was instantaneous and it now appears to be under control and looking like returning to the elimination of community transmission. Vietnam, Cuba and China with larger populations also responded instantaneously to second outbreaks with similar results. In contrast, several economically developed countries with containment strategies are struggling with subsequent outbreaks. Increased infections and mortality rates continue to be common outcomes of containment.

For some months Australia and New Zealand had similar outcomes per capita although, prior to the current outbreak, the former had a gradually increasing rate of infections due to its containment strategy. Its mortality rate per million is 19, low internationally but an increase of 4 over the previous week. Australia has now committed to shifting from containment to elimination.

New Zealand’s success has also meant that it doesn’t have to go into full national shutdowns in the event of further outbreaks of community transmission. Already the response to the current outbreak has to date been much less severe, and focussed on one cluster. We are in a stronger position partly through having previously achieved elimination, lessons learned, improved capability and new technology to arguably have even more refined and narrower responses to any future outbreaks compared with much of the rest of the world.

Liberal technocrat governments

New Zealand has been helped by having a government best categorised as ‘liberal technocrat’. Liberal technocrats respect science and data. Consequently it was responsive to the advice of public health specialists and other experts about focussing on elimination for community transmission.

It also meant that all parliamentary political parties more or less came into line on the elimination objective at least. Labour and the Greens were consistent. National and, to a lesser extent, NZ First were lured somewhat by the false dichotomy between health and the economy with their premature advocacy of coming out of the first national lockdown and loosening up on the borders but they haven’t criticised elimination. National also had an odd brief dabble into conspiracy theories.

ACT also supports elimination but has a bizarre position of wanting the private sector to take over quarantine facility control indicating obliviousness to the lessons of Melbourne and elsewhere. If adopted this would undermine elimination through likely uncontrolled community transmission.

The downside

But there is a downside to liberal technocrats. They lean towards elitism and a lack of peripheral vision. New Zealand was in a highly vulnerable and ill-prepared state to cope with a pandemic. This is despite the fact that after SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), part of the coronavirus family, breaking out in 2003 the Ministry of Health responded quickly by developing a pandemic plan. But, inexplicably at least with the benefit of hindsight, the plan was for influenza rather than virus pandemics. While there were helpful principles in the plan it was insufficiently fit for purpose for a virus pandemic.

Hospital Staff shortages

Further, our public hospital workforce through neglect, was in a poor state due to workforce shortages. This was especially the case for hospital specialists where, according to the best estimates, by the time Covid-19 arrived on our shores, shortages were almost one-quarter (at least 1,000). Consequently it was a workforce suffering not just fatigue but also burnout.

With acute patient demand increasing at a rate higher than population growth, public hospitals wouldn’t have coped had not the elimination strategy delivered by the severe lockdown been so effective. But it did mean that in order to prepare for an avalanche of Covid-19 admissions as happened in western Europe, patients requiring diagnosis (such as for cancer) missed out with some endangered and others dying.

Specialist shortages was a legacy left by the former National led government, but the Labour led government showed no sign of willingness to address the crisis. This included former Health Minister David Clark and the Director-General rejecting an initiative from the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists to address it through an accord.

PPE shortages

Dealing with the operational response to Covid-19 has revealed serious capability and capacity issues with the Ministry of Health. It failed to provide Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to the health workforce in a timely manner with the Ministry lacking the right capability to work with overseas supply lines (and having to be rescued by some of the larger DHBs). There was a related failure to monitor the standard of PPE already in national storage. As a result much PPE was damaged through deterioration.

Public-health Staff shortages

There was a failure to address serious public health staff shortages in order to undertake effective contact tracing in the lead up to and during the national lockdown in April. Another failure was inadequate understanding of what constituted patient confidentiality. This led to the unnecessary forwarding of confidential patient information to emergency responders and the subsequent leaking of it from within the National Party for political purposes.

Testing failures

What was most disheartening was the recent discovery that so many essential workers at our border security and quarantine facilities were not being tested despite, in a number of cases, of it being requested. Not only did this show disregard for the wellbeing of these workers, it also failed to recognise that they were the most at risk of spreading the virus to their communities.

The system was impressive in the instantaneous high level of community testing following the latest Auckland outbreak. Testing these essential workers was much less difficult, which makes the failure even more galling.

Need for a central public health agency

Learning from the big positives and the concerning negatives of New Zealand’s response to Covid-19 there are several initiatives that would form part of a prudent post-election strategic direction. Looking to the longer term and in anticipation of future pandemics and epidemics, the next government would be well advised to establish a new national public health agency separate from – but with equal status to – the Health Ministry. Its purpose would be broader than viral and influenza outbreaks, but its responsibilities would include pandemic planning for both. This initiative is strongly advocated by public health specialists such as Dr Collin Tukuitonga – Associate Dean, Pacific, at the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences of Auckland University.

So, what would a National Public Health Agency look like?

Epidemiology focused

Epidemiology would be at the core. A public health specialist wryly observed to me recently that half the country now think they are epidemiologists. So, to avoid any ambiguity, I’m referring to the branch of medicine which deals with the incidence, distribution and possible control of diseases and other factors related to the health of populations.

Health protection focused

But also at the core would be health protection. There is a largely unknown occupational group in DHBs called health protection officers. They are experts in environmental and communicable diseases. This requires skills in science, law and investigation. Examples of their functions are air quality, food safety, drinking water, hazardous substances and, of course, border control. These skills should form part of the expertise within the agency.

New Zealand has been well served in this crisis by having a public health specialist as Director-General. This added to government confidence in the advice being received over how best to respond to Covid-19, including whether elimination or containment (or even ‘herd immunity’). However, of the 5 Director-Generals to date this century, only 2 have been public health specialists.

Rather than leaving the experience of Director-Generals to the roll of the dice, it would be much more sensible to have a separate agency containing this specialised expertise rather than having it buried within the Ministry. The agency would play the leadership role for population health (including health protection) and, anticipating further pandemics or epidemics, for both the preparatory planning and responding.

Avoiding system disruption and distraction

Establishing a new central agency would take time so it will be necessary for the next government not to further disrupt or distract the health system by proceeding with the massive restructuring (creating mega DHBs controlled by a new national health bureaucracy) recommended by the Heather Simpson review of the health and disability system.

In fact, our smaller DHBs may be better placed to ensure effective testing levels and contact tracing. Cuba offers a useful insight. It is divided into local health systems serving defined populations of between 20,000-60,000. This, plus sufficient workforce capacity, enables every household to be visited annually for health check-ups including immunisation.

Only 3 DHBs come within this population range (Tairawhiti, Wairarapa and West Coast) although another 2 are a little above it (Whanganui and South Canterbury). The next government should require the health system to look at ways of extending testing to more vulnerable and less accessible populations including the option of home visits. But this will require DHBs to know their populations well and have sufficient workforce capacity. This will arguably be best achieved by funding and empowering strong regional community health bodies rather than imposing large central bureaucracies. I will deal with this issue in more detail in a follow-up piece on the dig.

Other post-election initiatives

Further issues the incoming Government would be wise to address in order to ensure amore resilient and responsive health system to deal with future outbreaks or health emergencies include:

Addressing Staff Shortages

New Zealand can’t afford to continue to have such severe shortages in their public hospitals. Hospitals should be staffed at least to continue diagnosis of patients who might have conditions that are life-threatening or otherwise harmful. Priority must be given to the serious shortage of medical specialists who are paying for this political neglect with their personal health. This means biting the bullet on salaries given the over 60% base salary gap with Australia with whom we unsuccessfully compete for specialists. It doesn’t mean a 60% salary increase but it does mean a less costly new salary structure providing a pathway to competitiveness.

Health Ministry Capacity

The Ministry of Health’s capacity and capability must be improved in the areas where we have been shown to be vulnerable. This is in the supply and storage of PPE, utilising periods after lockdowns better to extend testing, better understanding what constitutes patient confidentiality, and being more responsible in the care of border and quarantine security staff.

Back in March the Ministry established a technical advisory committee with an impressive composition of experts including public health specialists. It played an invaluable role helping give the Government more confidence in their decision-making. But since April it has been in virtual hibernation with its frustrated experts left to comment publicly on identified data access deficiencies and border security and recommended improvements such as masks. This committee should have both its status enhanced and have regular meetings so that its members are directly engaging with the Ministry. So much quality advice exists outside the Ministry which must be systematically tapped.

Essential Supply Chains

How our PPE and other essential supplies are provided requires review. Our dependence on international supply lines makes us vulnerable during a pandemic. While this dependence may still be necessary (and while it is, more plurality of supply lines should be followed through), reducing it through increased local production is also important. We are demonstrating this already with community face masks, but we should be exploring it for PPE and hospital equipment such as ventilators.

Wage Subsidy Policy

Finally, in the event of further outbreaks, the new government needs to reconsider how the wage subsidy is applied. Economist Bernard Hickey has written a challenging critique on the wage subsidy whereas, along with other measures, by paying it directly to eligible businesses favours the wealthy and powerful at the expense of the poorest. He gives the salutary example of Fletcher Buildings, The Warehouse and Sky City who together pocketed over $170 million from the subsidy and then laid off 2,700 workers. Hickey also contrasted the special benefit for those who lost employment through Covid-19 set at a rate almost double that of the standard ‘job seeker’ single person rate.

The new government could shift to a system of direct payment to workers in the affected business and move the rate for all recognised job seekers to the same as applying to those who are job seeking as a result of Covid-19.

Overall Assessment

The upshot of all this is that New Zealand is now much better placed to address these big-picture issues and undertake reforms that will put us in a better position to deal with any further COVID-19 outbreaks, future pandemics, or in-fact, with any major national public health emergencies such as natural disasters. The big question is, how committed will the next Government be to making the changes needed to ensure this transition?

There are several criticisms of the Health Ministry and wider Government performance over the response to Covid-19. However, it must never be forgotten that because of the overall success of its elimination strategy, these criticisms are of a relatively much smaller magnitude than almost all of the rest of the world which would love to have them as its biggest criticisms.

Questions For Citizens and Politicians

- Would you support the creation of a National Public Health Agency?

- Would you support addressing the severe public hospital specialist shortages by reviewing salaries in light of the huge pay gap with Australia?

- Would you support reviving and enhancing the status of the MOH technical advisory committee?

- Would you support a review of our Essential Supply Chains for PPE and hospital equipment?

- Would you support reconsidering how the wage subsidy is applied?

Answer These questions Below

Comment on This Article Here

Take Part in the Transition

The ScoopCitizen ‘engaged journalism’ service provides a safe and deliberative members-only ‘engaged journalism’ space.

ScoopCitizen is a place for learning, discussion of ideas and collective action using ScoopCitizen tools via our partnership with GovTech startup NextElection and engaged journalism methodology.

This is an attempt to bring more participation and engagement with you, our readers into the process of creating quality journalism.

Sign up to ScoopCitizen now to stay tuned and participate as we develop the conversation on the Transitional Democracy series.

If you want to support us to expand this conversation and bring on even more great journalists to cover these CitizenDesks please setup a one-off or regular donation to ScoopCitizen via Press Patron. All funds raised will go to creating more quality content on this issue.