Next up – the Greens. As a minor political party, the Greens will need to work in coalition or as a confidence and supply partner with a Labour-led government. Strong on the environment and Te Tiriti, the Greens have a set of policies designed to work alongside Labour’s, but with – arguably – a stronger commitment to social justice and equity. So, do the Greens’ policies stack up for Māori? Te Matapihi provides a perspective.

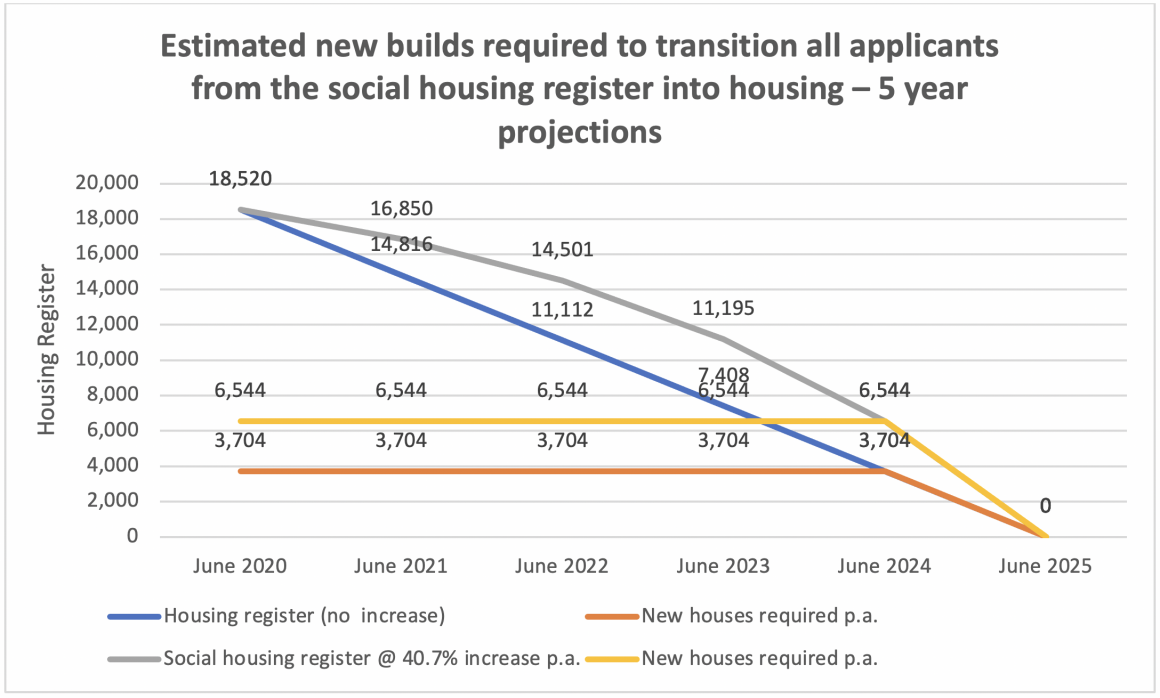

The Greens have released their flagship housing policy – Homes For All, which is a detailed and costed plan to create thriving towns and cities, supporting mana motuhake Māori and self-determination at a community level. The policy itself is not Māori-specific, but includes a number of Māori-specific initiatives, and is strongly underpinned by Te Tiriti o Waitangi and a sustained commitment to social justice.

The Home For All policy has five components:

- Using Kāinga Ora to deliver affordable new rental properties with the aim of clearing the public housing waiting list within 5 years and providing pathways to home ownership through progressive ownership options.

- Support Te Tiriti o Waitangi and community-driven housing development by fixing funding and regulatory barriers to papakāinga and cohousing

- Increased professionalisation and regulation of the rental sector, including funding to enable community housing providers to offer affordable long-term rentals, review of the accommodation supplement, warrant of fitness for rental homes, and better standards of tertiary student accommodation.

- Promote environmentally sustainable and inclusive urban development through Crown developments and improved planning provisions.

- Ensure every home is safe, warm and dry by overhauling the Building Code and making COVID-19 recovery stimulus available to additional energy efficiency initiatives.

The Future of Transport policy also touches on housing in terms of promoting transit-oriented housing development in urban areas, fast inter-city commuter rail, light rail initiatives in Wellington, rapid transport and better walking and cycling infrastructure in fast-growing regional cities.

The Clean Energy Plan has a number of policy items relating to housing:

- Equip all suitable public housing with solar panels and batteries, including new public housing, saving people on their power bills and enabling them to share clean energy with their neighbours.

- Make it 50% cheaper for everyone to upgrade to solar and batteries for their own homes, with Government finance.

- Create a $250 million community clean energy fund to support communities, iwi, and hapū to build solar arrays and share lowcost, clean energy with their neighbours.

The Poverty Action Plan includes the introduction of a net wealth tax, which will address the current under-taxation of investment property that is contributing to housing market inflation.

We’ll be

limiting our discussion to three key policies, which we think have the

potential to make a difference for Māori. These are:

- Clearing the housing waiting list

- Supporting papakāinga and Māori housing solutions

- Seed funding and underwrites to support community housing

For each of the selected policies, Te Matapihi have asked ourselves two questions – will it work? And will it make a difference for Māori?

1. Clearing the housing waiting list

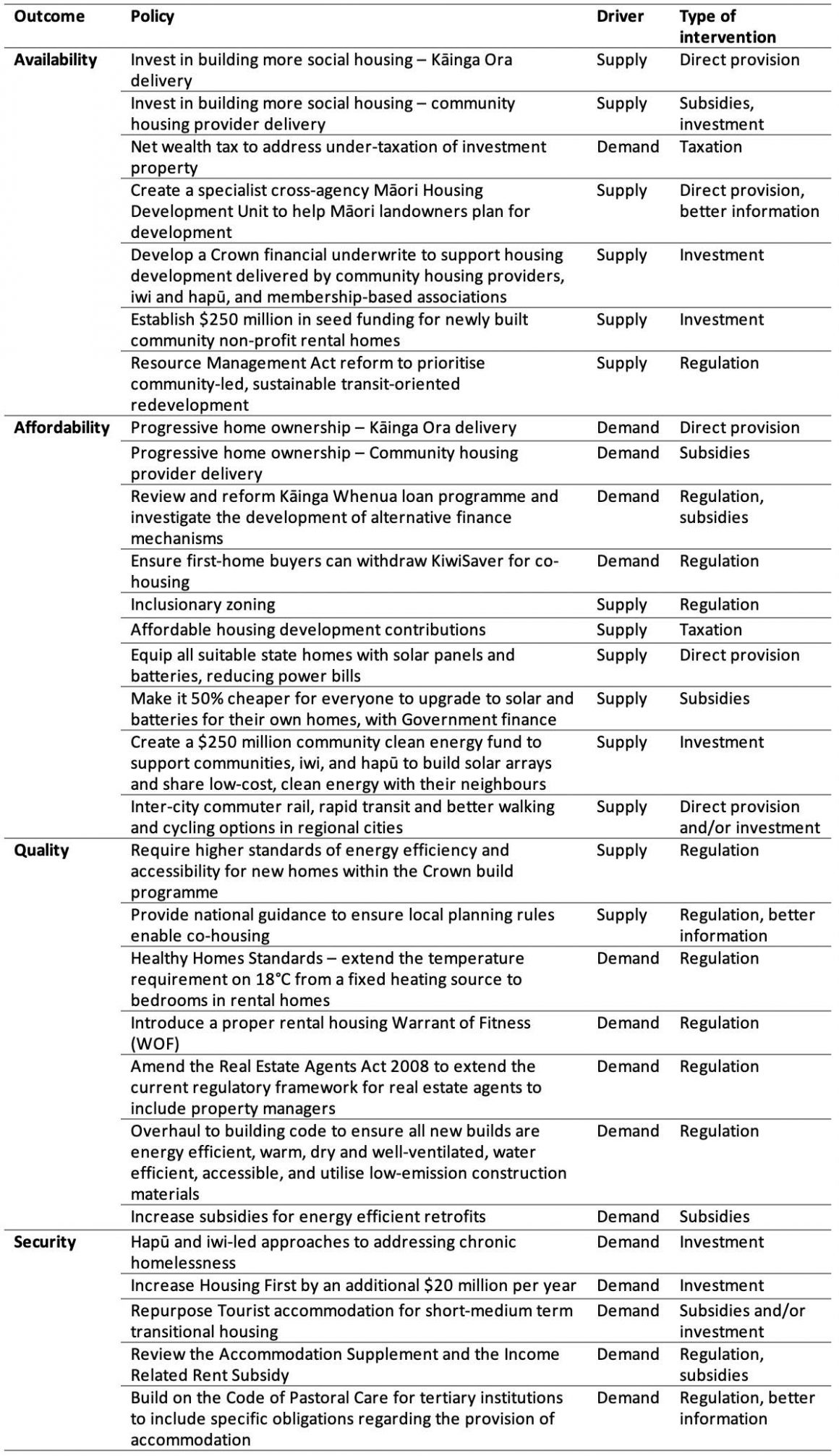

There are currently 18,520 applicants on the Housing Register. The Greens policy aims to transition all applicants off of the social register and into housing within the next five years.

Chart 1. Changes in the Housing Register 2015-2020

Note: Applicant figures are from the Housing Register only – the Transfer Register has been excluded.

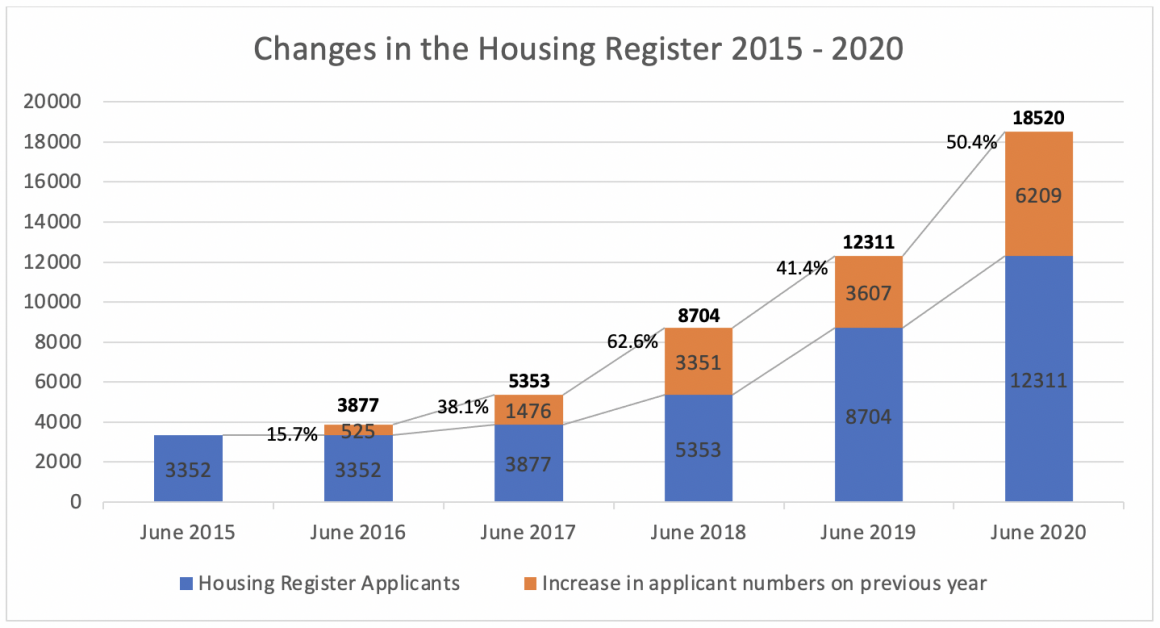

Chart 2. Changes in Public Housing Stock Levels 2015-2020

Note: Public housing figures from the Public Housing Quarterly report produced by the Ministry of Social Development (June 2017) and the Social Housing Quarterly report produced by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (June 2018, June 2019, June 2020).

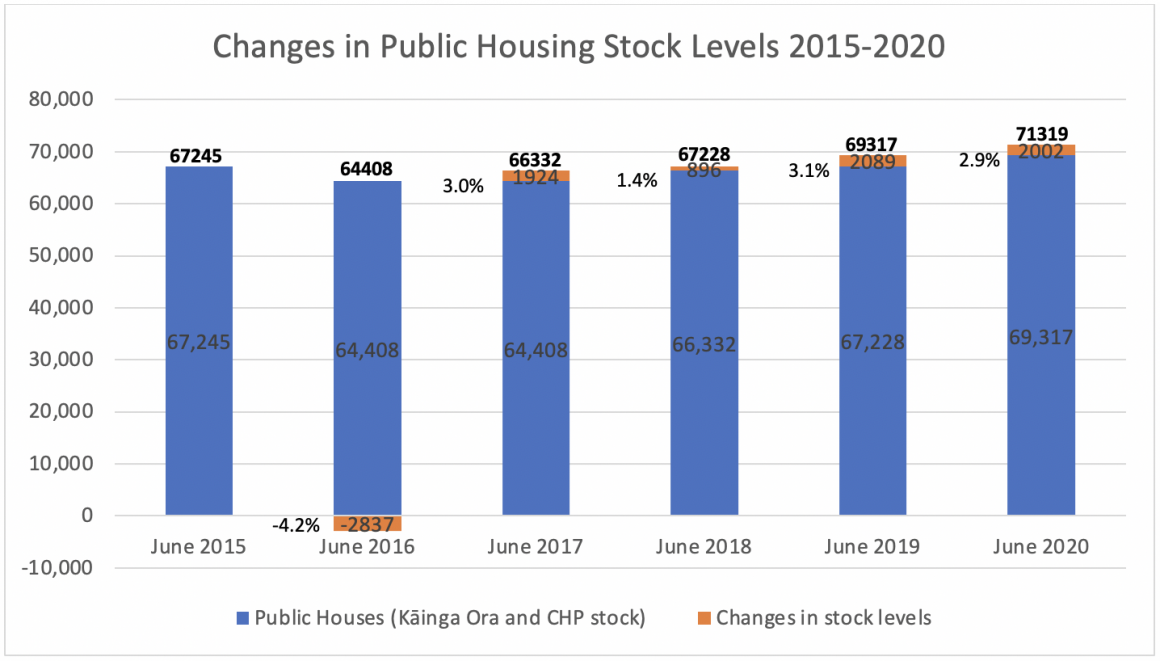

Chart 3. Estimated new builds required to transition all applicants from the social housing register into housing – 5 year projections

Note: 40.7% growth rate calculated based on the Compound Annual Growth Rate over the previous 5 years (average Annual Growth Rate calculated at 41.6% over the same period). June 2020 ‘new houses required per annum rate based on Compound Annual Growth Rate – Public Houses of 1.2% over the previous 5 years.

Will it work?

In the 2018/19 financial year, Kāinga Ora built 1,461 new state homes. The June 2020 Public Housing Quarterly Report saw an increase of 2,002 public houses (provided by both Kāinga Ora and Community Housing Providers) from June 2019. Assuming demand continues to rise at a rate of 40.7% on average, Kāinga Ora and Community Housing Providers will need to build new homes at a rate of 6,544 per year over 5 years. Should there be no increase in demand, and no further stock divestment, 3,704 houses per year would be sufficient to eliminate the waiting list within 5 years.

At 6,544 dwellings per year, this would increase the current number of new houses built by Kāinga Ora and Community Housing Providers annually by 327% (assuming approximately 2002 homes are currently built by Kāinga Ora and Community Housing providers each year). For context – over the past 12 months (September 2019 to August 2020), 37,467 consents for new residential units were issued nationwide. Assuming an additional 4,542 units (in addition to the current 2002) will be built per year under the Green party policy, new public houses would represents 15.6% of all consents / new builds nationwide.

The Green Party policy states that they will scale up the Crown build programme (delivered by Kāinga Ora) up to 5,000 new homes per year. Accounting for annual increases in the housing register, we believe an additional 1500 will be required to clear the waiting list within this timeframe. Considered alongside the other Green Party policies, it is possible that some of the homes built under the long-term affordable rental policy would be occupied by people who might otherwise go onto the waiting list, which could reduce the annual number of additional public houses required.

The current housing crisis is structural and deeply entrenched. For this to work over a longer time period, social housing building volumes would need to beincreased, and demand side policies implemented.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

On the social housing register (as at June 2020) 9,162 or approximately 50% of applicants are Māori, an increase of approximately 161% compared to the same time last year (from 5692). The rate of increase overall was approximately 150.4% (from 12311 in June 2019 to 18520 in June 2020).

Additionally, many Māori households living in housing deprivation may not be represented on the social housing register, due to living in poor quality owned homes (generally in rural areas, generally on whenua Māori), and specific policies will need to be developed to address this issue.

Will it make a difference for Māori – yes, provided there is no further stock divestment, and a Labour-led government (with the Greens as a coalition or confidence and supply partner) commits to increasing building of social housing by Kāinga Ora and Community Housing Providers, and implementing demand-side policies.

2. Supporting Papakāinga and Māori housing solutions

The barriers to developing whenua Māori for papakāinga are well-documented (including district plan provisions, landlocked blocks, difficulty gaining agreement amongst owners, Māori land court issues, and access to finance). The Green Party policy includes two key initiatives:

- Create a specialist cross-agency Māori Housing Development Unit

- Review and reform the Kāinga Whenua loan programme

Will it work?

Te Puni Kōkiri (the Ministry of Māori Development) has a broad mandate to support Māori development. They are responsible for leading public policy for Māori, advising government on Government-Māori relationships, providing guidance to government about policies affecting Māori wellbeing, and administering and monitoring legislation.

The Māori Housing Network – Te Puni Kōkiri provides a broad range of housing-related services, including home assessments and repairs, papakāinga feasibility planning, infrastructure to whenua Māori, transitional housing, whānau capability building and resources / information. New builds form a comparatively small part of the overall work programme.

From 2011- October 2015, Pūtea Māori (administered by the now-disestablished Social Housing Unit, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment) funded the building of 95 new homes. Between October 2015 (when the Māori Housing Network was established) and 30 June 2019, the Māori Housing Network Te Puni Kōkiri co-funded 102 new affordable rental homes on papakāinga.

Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities has an explicit development mandate. The entity has two key roles – “being a public housing landlord” and “partnering with the development community, iwi and Māori, local and central government, and community organisations to lead an facilitate urban development projects of all sizes”. In 2018/19, Housing New Zealand Corporation (prior to the establishment of Kāinga Ora) built 1,461 new state houses.

The establishment of a cross-agency development unit provides the opportunity – without any additional budget allocation – to combine the community relationships and Māori development expertise of Te Puni Kōkiri, with the development capability and capacity of Kāinga Ora. This will ensure Māori landowners have access to the development powers and resources available to Kāinga Ora. Although the potential impact is difficult to quantify, over time this could significantly increase housing development on whenua Māori.

Reform of Kāinga Whenua has been called for by Māori landowners and advocates (including Te Matapihi) since its inception in 2009. Although significant changes were made to lending criteria between 2012-13, lendee uptake remains low. As at June 2019, a total of 42 loans had been settled, nine were in the process of being drawn down, and five had received pre-approval. By comparison, 1,268 Welcome Home Loans (the mainstream product on which Kāinga Whenua was modelled) were processed in 2018/19, and 1,674 in 2017/18.

The Green Party policy states that the reform of Kāinga Whenua would form part of a more comprehensive reform agenda. Te Matapihi has long advocated for a comprehensive Māori housing reform programme, including the reform of Kāinga Whenua and the development of additional and alternative finance mechanisms, and would welcome the opportunity to be involved in shaping this programme should Labour and the Green Party be in a position to form government.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

Yes. Ongoing and sustained work will be required to address the long-term structural barriers to developing whenua Māori for papakāinga, but reform of Kāinga Whenua, as well as the development of a specialist cross-agency development unit will go a long way to empowering whānau and hapū Māori to develop their land for papakāinga.

3. Increasing the supply of affordable rentals

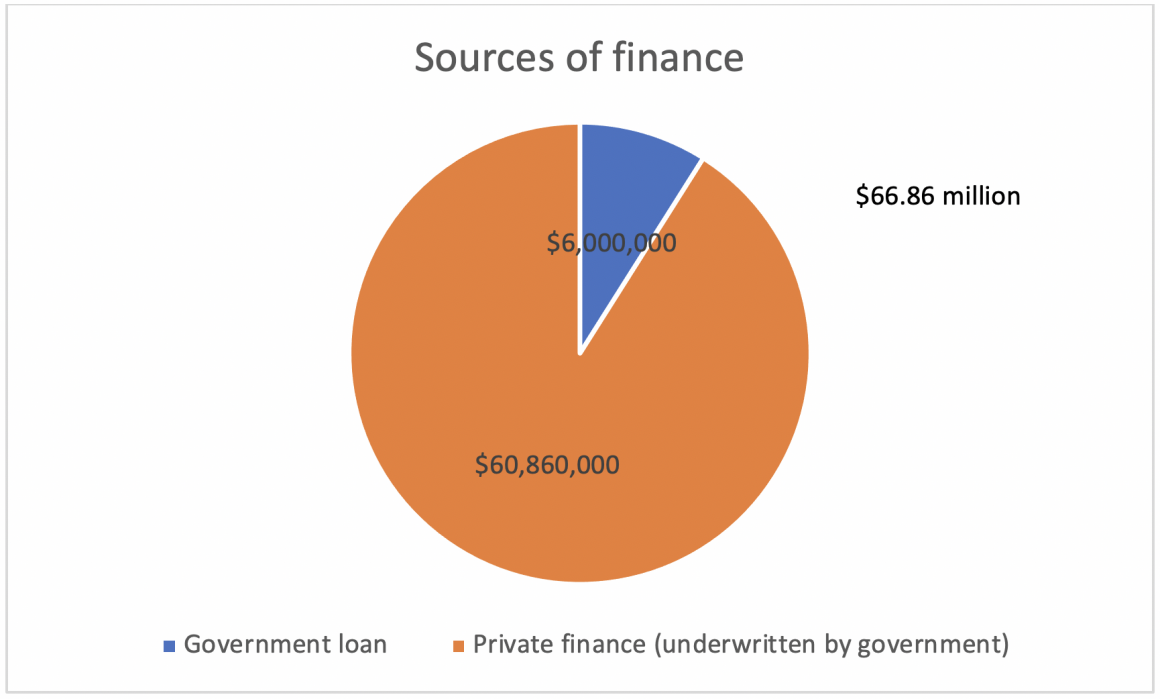

The Green Party policies proposes a Crown underwrite to support housing developments delivered by Community Housing Providers, iwi and hapū, and member-ship based housing organisations. The policy also advocates for the establishment of $250 million in seed funding for newly built community non-profit rental homes.

Will it work?

We’ll test this out using the example scenario in the policy.

| The development, which consists of 150 homes across five apartment blocks includes 40 KiwiBuild homes, 50 progressive homeownership homes, and 60 long-term affordable rentals. The Crown underwrites the development and provides a $6 million Crown loan to assist the community housing provider to obtain further private finance. The Crown’s loan is paid off within one year of the completion of the build using the proceeds from the sales of the KiwiBuild homes. The Community Housing Providers expects to pay off their loan in 30 years. |

Please note: this is a crude calculation that does not take into account GST, inflation, interest rate fluctuation, or interest paid during the construction period.

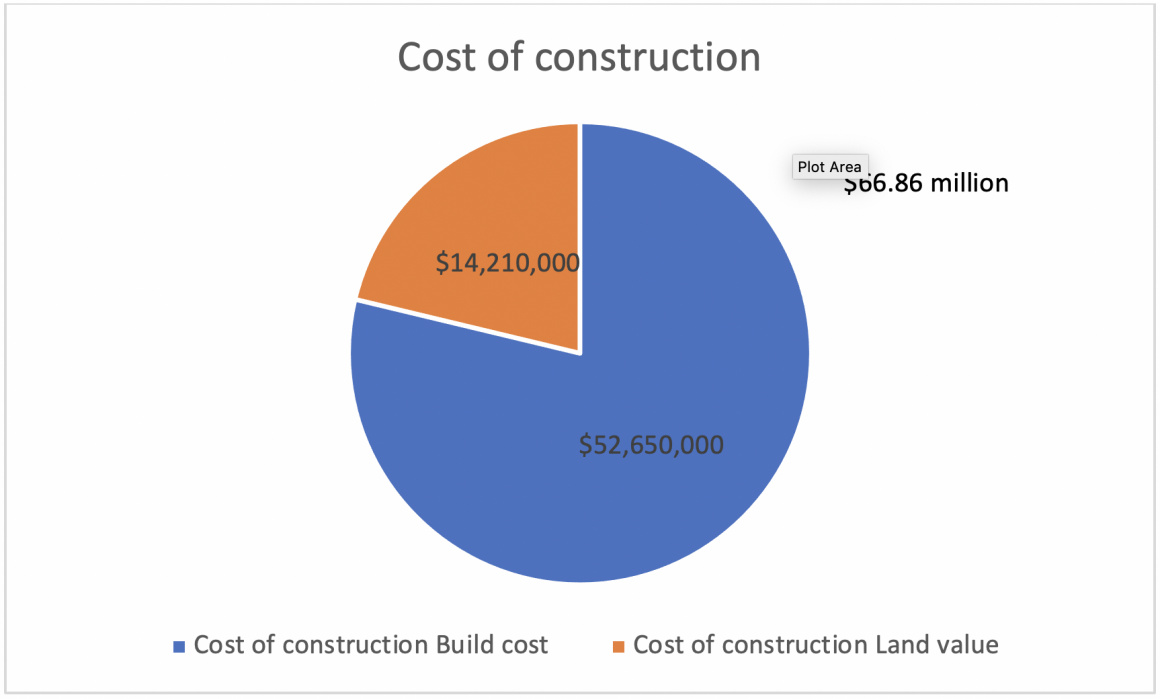

Construction costs

We have assumed 30 units per building over 3 stories.

We have assumed a build cost of $4,500 per m2 (using QV cost builder base rates and making an allowance for site works, servicing, professional fees and contingencies).

Studio / one-bed – 40m2 x 50 no. = 2000m2

Two-bed – 65m2 | 65m2 x 50 no. = 3250 m2

Three-bed – 90m2 | 90m2 x 50 no. = 4500 m2

9,750m2 total + 20% (allow for circulation and services) = 11,700m2

Build = $11,700m2 x $4500 = $52.65 million

We have factored in the land using an indicative site on the

Isthmus in Tāmaki Makaurau. Based on an equivalent development, we estimate the

area of land required for the development to be 7,000m2, at a cost of $2030 per

m2, for a total of $14,210,000. For this estimate, we have used the 2017

general property revaluation (this was due to be revised in 2020 but has been

deferred due to COVID) of $1400 per m2, factoring in a 45% increase (based on

average land value increase from 2014 to 2017).

Land value = 7,000m2 x $2030 = $14.210 million

Total construction cost = $60.86 million

Chart 4. Cost of construction – example development

Chart 5. Sources of finance – example development

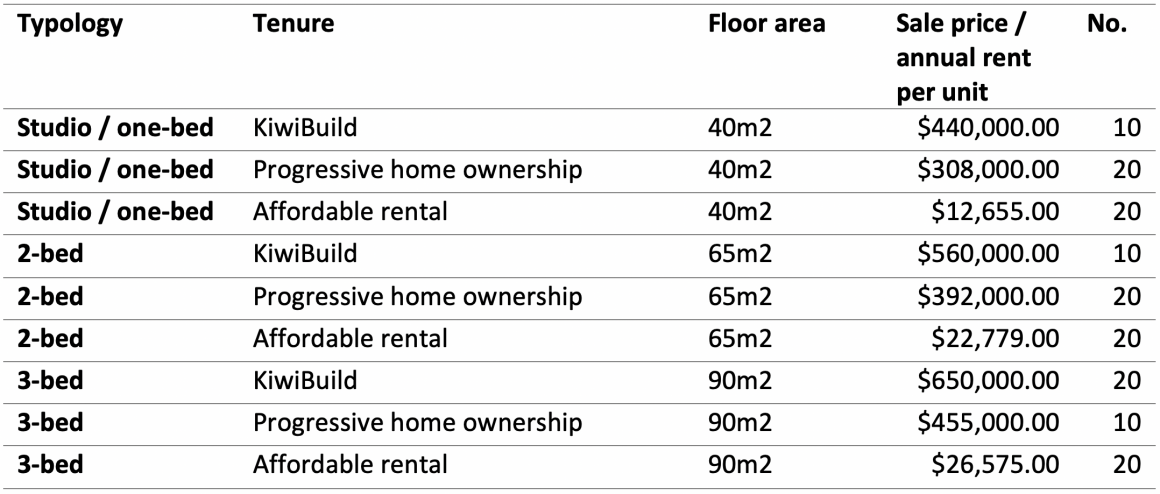

Tenure Split

Table 2. Tenure split – example development

KiwiBuild

For KiwiBuild first home buyer units, we have assumed the sale prices as per the above table.

We have assumed that the KiwiBuild homes will be sold in the first year, returning $23 million.

10 x KiwiBuild studios – $440,000 x 10 =

$4.4 million

10 KiwiBuild 2-bed – $560,000 x 10 = $5.6 million

20 KiwiBuild affordable rental – $650,000 x 20 = $13 million

$6 million will be used to pay off the government loan, whilst the remaining $17 million will be paid towards the principle.

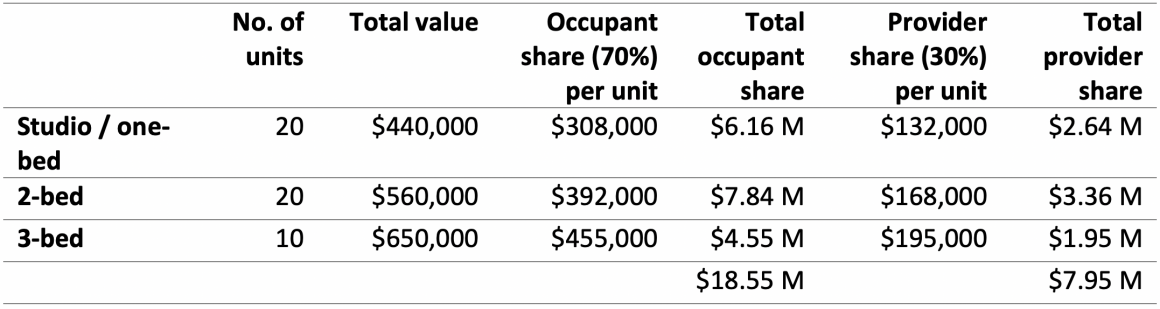

Progressive home ownership

Three types of progressive home ownership are available, including shared ownership, rent to buy and leasehold. We have assumed shared ownership will be used in this example.

Table 3. Progressive home ownership – example development

The occupant share will be sold in the first year, returning $18.55 million,

which is paid towards the principle.

Retained equity share (by provider) – $7.95 million

We have not allowed for tenancy management / wrap-around services. We have assumed maintenance and rates to be paid by occupant.

Long-term affordable rentals

Housing is generally considered ‘affordable’ if households are spending 30% or less of their disposable household income on housing costs. The median annual household disposable income (after tax and transfer payments) for Auckland for the year ended June 2019 is $78,461. The median annual household equivalised disposable income for Auckland is $42,183. Using this method, household members are made equivalent by weighting according to their age using the OECD equivalence scale.

- For one-bedroom units, we have assumed 1 adult ($42,183 x 1) = $42,183 median annual household disposable income.

- For two bedroom unit, we have assumed 2 adults and one child under 14 ($42,183 x 1.8) = $75,929 median annual household disposable income.

- For three bedroom units, we have assumed 2 adults and 2 children under 14 ($78,461 x 2.1) = $88,584 median annual household disposable income.

By this measure, we have assumed affordable rents will be set as follow:

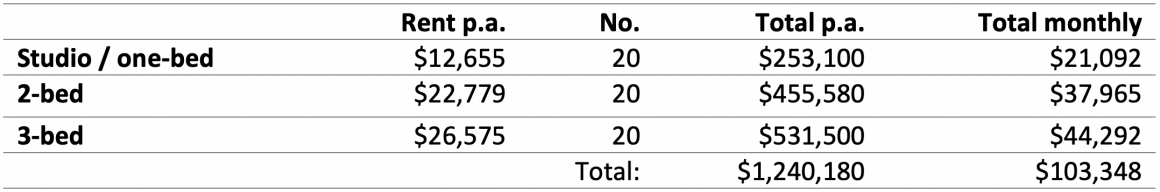

Table 4. Affordable rental income – example development

We have not made any allowance for the Income-Related Rent Subsidy.

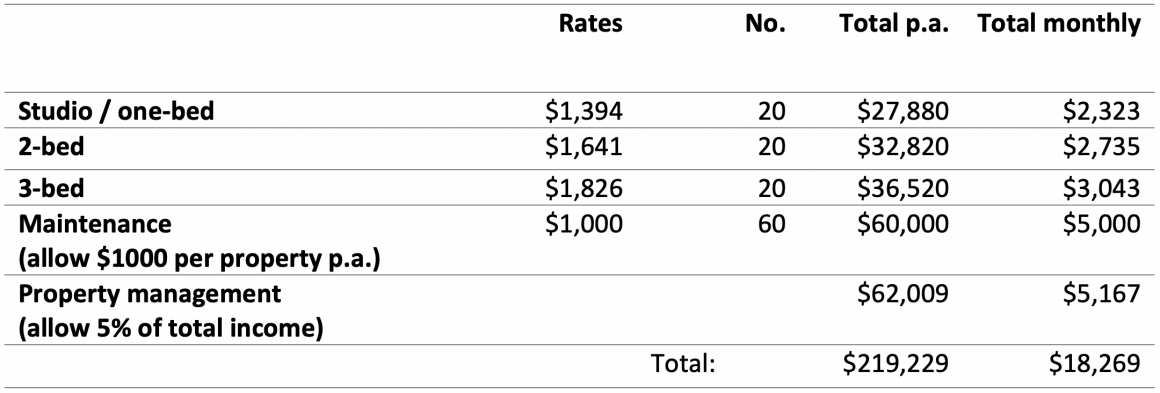

Maintenance (allow $1000 per

property per year) – $60,000 annual

Property management (allow 5% of overall) – $62,000 annual

Rates – 1-bed ($1,394 per unit) x 60 = $69,700

Rates – 2-bed ($1,641 per unit) x 60 = $82,050

Rates – 3-bed ($1,826 per unit) x 60 = $91,300

Table 5. Affordable rental outgoings – example development

Monthly operating costs = $18,269

Monthly income remaining after operating costs = $85,079

Repayment of principle

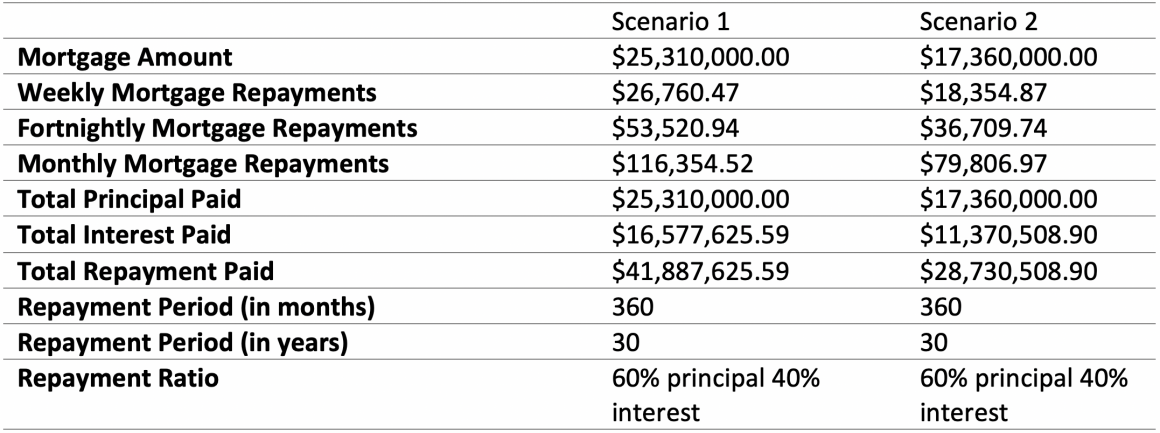

At this point, the principle is now $25.31 million.

Table 6. Mortgage repayments – example development

Mortgage repayments calculated using the interest.co.nz mortgage calculator. 3.69% interest rate assumed.

Monthly mortgage repayments = $103,363.

Based on our modelling, there is a $18,284 monthly shortfall.

For the affordable rentals, we have not made any allowance for the Income-Related Rent Subsidy – accessing the subsidy for some rental properties would raise the amount paid to market levels and increase revenue.

Additional revenue and zero-interest finance may be available to support the Progressive Home Ownership component. The current government Progressive Home Ownership pilot includes long-term interest-free loans and grants for tenancy services, and in all likelihood will be extended (provided Labour and the Greens are able to form a government).

If an additional interest-free long-term government loan of $7.95 million (plus potentially additional grant funding to cover tenancy management and wrap-around services) is made to cover the shared equity component, which could be repaid once the occupants repay their mortgage for the 70% occupant share, and take out a second mortgage for the 30% provider share. If a longer-term interest-free government loan is received, that number is brought down to $17.360 million, with monthly mortgage repayments of $79,807.

Will it work?

Broadly, yes. To work in an Auckland context, the interest-free government loan would need to be increased, potentially to cover the provider-retained component of progressive home ownership properties. Accessing the income-related rent subsidy for some affordable rental properties would also increase income (and therefore project viability).

Will it make a difference for Māori?

Māori median incomes are lower overall – this may impact access, particularly in an overheated market like Auckland. One potential criticism of the KiwiBuild policy is the focus on one-, two- and three-bedroom properties, rather than the larger whānau homes required by many whānau Māori. Providing larger homes as part of the affordable housing component may threaten the viability of the model (unless the tenure split or levels of government investment are reconsidered).

That said, the example above is just that – an example. Long-term interest-free government loans, as well as government underwriting to enable providers to access private finance, have the potential to support providers, including iwi, hapū and Māori community providers, to deliver stable, healthy, affordable housing embedded in transit-oriented communities.

Disclaimer: The lead author of this series, Jade Kake, provided contracted independent policy advice to the Green Party, which contributed to the development of the Homes For All policy. Policy advice was restricted to the ‘supporting papakāinga and Māori housing solutions’ and did not form part of the ‘clearing the housing waiting list’ or ‘increasing the supply of affordable rentals’ policy items. This policy advice was provided in an independent capacity and not on behalf of Te Matapihi, which is a non-partisan organisation. The Green Party have been provided with the opportunity to review our analysis.

This is the third article in Te Matapihi’s Māori housing election year series. Each of the subsequent articles will tackle a political parties housing policy, under the sub-headings of availability, affordability, quality and security, with a focus on what these all mean for Māori. The series will conclude with a ‘scorecard’ comparison of what works, what doesn’t, and what’s likely to make a difference for Māori.