Image: Pīngao glows orange in the late sun at West Ruggedy beach, Rakiura National Park, Stewart Island, New Zealand. Photo: Dave Hansford/Origin Natural History Media

As often as she can, Betsy Young takes a strand of pīngao to a local school in the Far North to share a sad love story.

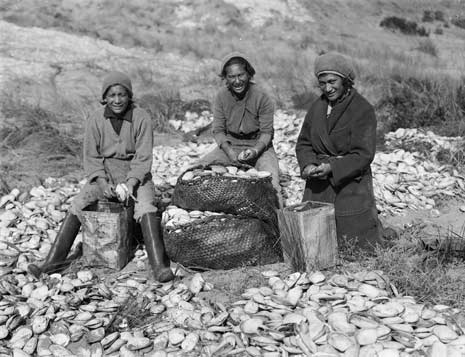

Toheroa was once a staple for Māori in Northland – the seafood delicacy of the 1900s. Local canneries ran at capacity for many years, until harvests dwindled. But despite bans on commercial and recreational harvests that have been in place from the 1970s, toheroa has not recovered in the decades since and science is looking to traditional knowledge to work out why.

For three summers from 2003, Young was part of a project to restore toheroa beds along Northland’s beaches. “Pīngao was our marker of where we planted toheroa,” she says. The clams were collected and replaced along several new sites, identified through mātauranga about relationships within the dune ecosystem.

When conservation minister Eugenie Sage launched the discussion document for a new biodiversity strategy, Te Koiroa o te Koiora, last month, people in the room needed no reminders that more than 4000 native species are at risk or threatened with extinction.

The few examples of improving population statistics, including rowi kiwi, takahē and mōhua, are like rogue data points in an overwhelming trend of continued decline.

In her vision for a future in which we become better at safeguarding nature, Sage called for an accelerated transition to a “landscape approach” to conservation that recognises the mauri and interconnectedness of ecosystems and the people within them.

One of the speakers, Richard (Blandy) Witehira from the Bay of Islands, (Ngāpuhi, Whakatōhea, Tainui.) filled out this vision with the frequently rough reality on the ground when he recounted the early days, back in 1998, of trying to convince his own iwi to sign a Ngā Whenua Rāhui covenant to protect 1600 hectares of native forest at Rāwhiti. The Ngā Whenua Rāhui trust works with Māori landowners to protect places of biological or cultural significance. Today, there are 272 agreements protecting 180,684 hectares, but back then, many were unconvinced.

A deep-seated mistrust and fear that a covenant was no more than another land grab in disguise was the first response to Witehira’s proposal, followed by legal challenges and threats of violence, particularly when he argued for 1080 as a pest-control tool. But years down the track, locals now listen to brown kiwi at night and toutouwai and kākāriki have returned to the region. Five people are in full-time jobs and many more have regained something even more precious – a renewed “connection with their whenua” as they work to restore the health of the environment.

Witehira wants to see a collaborative approach between hapū and iwi, government organisations, NGOs and local authorities, led by the people of the land. “The secret to solving this biodiversity crisis is to hand the kaitiaki status back to indigenous people.”

This is a sentiment that echoes through many conversations.

Dr Daniel Hikuroa’s main research interest at Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, at the University of Auckland, is in the integration of mātauranga and science. Hikuroa (Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato-Tainui, Naati Whanaunga) is quietly encouraged by the level of mātauranga Māori included in the biodiversity strategy – in ways that go beyond “let’s have a pōwhiri and say a karakia and then we’re all done”.

Within a Māori worldview, he sees several concepts as particularly relevant to improving how we approach environmental crises, be it the loss of biodiversity or climate change. “Whakapapa is a key value for a number of reasons. It explains the world, it’s our cosmology, it explains to us and gives us teachings around how we belong and how we fit and make sense of the world.”

Whakapapa offers the beginnings of a more holistic framing, or a way of thinking that acknowledges that everything is connected – as in Young’s stories about pīngao, toheroa and healthy dunelands. “Already you’re moving between the marine realm and the terrestrial realm, which can be a challenge for legislative frameworks. Yet within the Māori way of thinking, there is no boundary,” Hikuroa says.

Another critical concept is kaitiakitanga. Hikuroa was disappointed with the English translation as stewardship. “A steward is someone who looks after somebody else’s property.”Begrudgingly, he accepts guardianship as the best English term. “Guardianship is more aligned with Māori framing but even then, the power relationship isn’t quite correct because within whakapapa, we are the youngest, the last born.”

This requires a fundamental mind shift, Hikuroa says, that realigns our relationship with nature and acknowledges that we depend on it. “Kaitiakitanga, at its core, is about managing human interactions with the environment, not the environment itself. We are the little ones in this relationship, so we’ll manage ourselves and our activities for a better outcome for our elders.”

He says if Māori, and indigenous people elsewhere, were given “māna motuhake” (autonomy and trust) – nature would stand to benefit. “I strongly believe that in many places where the knowledge system is still strong, where practices are still there, if we can enable people to carry out their tikanga, to carry out their kaitiakitanga practices by giving them māna motuhake, then they will deliver on biodiversity outcomes for Aotearoa New Zealand.”

As researchers continue to retrieve and reinterpret long-held traditional knowledge, it is already delivering tools that are as precise as ecological science but enfold connections across natural systems. The maramataka, or Māori calendar, is one example. The complex system builds on observations of seasonal changes – the flowering of plants or the migration of animals – and fixes them to the appearance of certain stars.

Some stars mark the transition between seasons, while others point to more specific events, such as days when flounder come further inshore or rats are more active. The predictive power of the maramataka is so finely tuned, that “it is the best – and critical – framework that begins to notice the effects of climate change”, Hikuroa says.

Sharing observations made by tohunga Rereata Makiha, Hikuroa points to the flowering of kohurangi, or Kirk’s tree daisy, which was used as an indicator that it was safe to plant gardens because there would be no more frosts. The epiphyte now flowers more than a month earlier, out of rhythm with the stars.

The Raukūmara ranges represent one of the largest stretches of native forest left in the North Island. The bush should be reverberating with the song of kākā and kōkako, but instead, 1000-year-old tōtara are dying and the forest floor is mostly empty, browsed to death by deer while possums are eating holes into the canopy. Horopito, a peppery shrub that is unpalatable to introduced mammals and native birds alike, still stands. “It’s a ngahere that has no kai,” says Ora Barlow-Tukaki (Te Whānau-a-Apanui), who is part of a tangata whenua group working to save the forest.

The Raukūmara Conservation Park was among the last to be hit by deer and possums during the 1970s. Initially, hunters kept deer populations in check, but then the market for feral venison collapsed. The last possum control operation was more than two decades ago.

As the forest giants wither, so does the language that once described the traditional foods people could gather from the bush. Few people remember the names of trees, and some now think of deer and feral pigs as the new traditional food. They have forgotten that the introduced animals are killing what was once the people’s mahinga kai, says Barlow-Tukaki. “Recovery needs to be bigger than a strategy. It’s about the language and the connection to the land. The ngahere is our tuakana. It wants to live and has to be given a chance to live.”

Two decades ago, Huhana Smith (Ngāti Tukorehe, Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga, Pai rawa atu), the head of Massey University’s arts school, faced a similarly devastating and complex challenge at her ancestral home at the Kūkū estuary, between the Ōhau and Waikawa rivers on the Horowhenua coast. Back in the early 70s, a loop of the Ōhau had been diverted by the local catchment board as part of a flood protection scheme. “But what that did was to create a stagnant river remnant in very poor condition with poor water quality, dangerously high ammonia levels in some parts, and guaranteed to kill cows if they drank from it.”

It was the iwi’s healers who first raised concerns about the lack of clean freshwater, and then the community realised that its dairy farm was a contributing factor. “We realised that we were complicit in our own ecological decline because we emphasised a certain economic basis.”

With the support of the Ngā Whenua Rāhui trust, they decided to restore the dune wetland Te Hākari to better balance the farm with the ecosystem. Seventeen years after the first plants went into the ground, “it’s fantastic to see a serious forest growing down the coast”.

It’s not perfect. Hornwort regularly invades the wetland, but the “reality of restoration is that you’re dealing with a transformed landscape, an agriculturally modified landscape that is trying to recover its memory of being a wetland again”.

Smith says the goal was not an unattainable pristine state, but a revitalisation of ecology and tikanga to bring Māori protocols back to environmental protection and biodiversity enhancement. Although scientific experts joined the project, they had to come in a tikanga Māori way by “going through the portal of the marae, the waha roa, across the marae ātea, the whare tūpuna, the whare kai, do the dishes and then out on the whenua”.

Collective effort and decision-making are critical points of difference to a purely scientific approach, she says. “We’ve all had to learn to reconnect to that kind of thinking. You have to humble your human self in relation to that kinship, because you’re not the dominator, you’re actually an active participant amongst it, and you have to lose that sense of I, or self.”

Let iwi and hapū lead in these areas, she says. “They want to do the active groundwork because it’s their whenua. It’s the indigenous knowledge systems of the world that will help sort things, but it’s not at the expense of those people. It should be at the propping and the support of people rather than a token acknowledgement.”

Just as discussions about a new biodiversity strategy get underway, the government issued a formal response to a Waitangi Tribunal claim that was lodged some 30 years ago. Known as Wai 262, it is a bid for legal protection of Māori intellectual and cultural property rights and authority over indigenous flora and fauna – fundamentally a claim about how the future should look. In the tribunal’s own report about the claim, it describes what Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research conservation biologist Cilla Wehi (Pākehā with family affiliations to Waikato-Tainui) describes as “whanaunga” – the building of kin relationships through acute observations of the natural world.

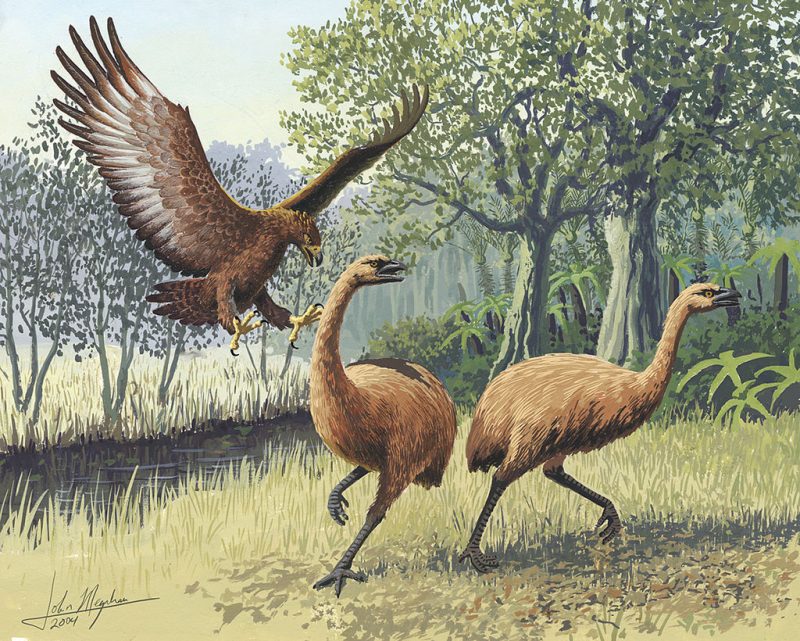

These are preserved in short proverbs, or whakataukī, which Wehi studies to understand how aware early Māori were of their new and changing environment. “The fact that there are so many about moa demonstrates awareness of the loss and the wider problem of extinctions,” she says.

Whakataukī also show that some of the processes people use to protect the environment, such as placing a rāhui, were practiced elsewhere in the Pacific and Māori brought them with them. “As with many indigenous people around the world, if you’re living very closely in a relationship to the environment around you, you will have an immense knowledge of processes of the ecosystems.”

One indigenous approach that inspires Wehi, is a concept developed by Canadian elders called two-eyed seeing. “It’s a good analogy of how we could see the contribution of both modern science and mātauranga. Imagine how you see the world – one eye is how you see the world through science, the other is an indigenous way of seeing. For any given problem, your eyes don’t have to be the same strength, but by using both eyes you have a much greater field of view and understanding that you can bring to the problems you are trying to solve.”

Such concepts could be of great value in the challenge we face as a country of protecting and restoring biodiversity through a synthesis of traditional Māori knowledge and science.

—

Ways to engage

The Dig does not have a comments section, however Members can Discuss this article in the Scoop Citizen Community Forum (Open to Scoop Citizen Members only)

We will be publishing more journalism by some of NZ’s top environmental journalists right here over the coming weeks. Please subscribe to Scoop Citizen for updates and a chance to engage in the journalism process here.

Click here to join Scoop Citizen >>>

Learn More:

For a good overall summary of the key points of the Te Koiroa O Te Koiora discussion document, see Scoop’s Explainer on the NZBS here and Co-editor Ian Llewellyn’s discussion of the National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity (NPSIB) here. Also check out Scoop’s Biodiversity Full Coverage page here.

You can also learn more about the DOC-led public engagement process, including events around New Zealand here.