The Simpson Report on NZ’s health and Disability system has laid out a blueprint for widespread reform and centralisation. The next Government will decide whether, and how, the report is implemented, but do its proposals amount to a positive direction for NZ? Will the massively disruptive structural reforms it suggests actually lead to better overall health outcomes, or provide more voice for people involved in the health system, either as workers or as patients?

Ian Powell analyses the report and provides an alternative view on the reforms really needed to achieve a people-centered health system for New Zealand.

Guided autocracy

President Sukarno – Indonesia’s first post-colonial president, was an insightful and widely beloved politician who led a huge and diverse new nation from 1945 until the installation of a brutal military dictatorship in 1965. In 1959 he introduced a policy labelled ‘guided democracy’ which, although more guided than democratic, was relatively benign compared with both the preceding Dutch colonialism and the military autocracy that followed him. The Heather Simpson chaired review of New Zealand’s health and disability system has an element of Sukarno in it but without being either insightful or benign in a health system context.

Sukarno was about both ‘what’ and ‘why’. In contrast Simpson is predominantly about ‘what’ and weak on ‘why’. Whereas, under Sukarno, Indonesia was seeing democracy expanding, the Simpson review proposes a less democratic health system. Rather than ‘guided democracy’ a more appropriate label of its report is ‘guided autocracy’.

Part of this ‘guided autocracy’ is the suppression of voice and marginalisation of health professional and public engagement through the imposition of a more centralised and authoritarian leadership culture in the health system. The recent assault led by the Ministry of Health on the leadership of the Canterbury District Health Board provides further insights on how decision-making under Simpson would operate.

Why the Report matters

Whether, and to what extent, the Simpson report (made public in June 2020) is implemented is a matter for the post-election Government. Most political parties are cautiously not declaring a clear position on the report’s recommendations. Labour has supported the direction of the report without elaborating on why… Health Minister Chris Hipkins supports replacing our current district health boards with a smaller number of ‘mega DHBs’. Unfortunately, he has declined to identify how many (and which) DHBs would be absorbed by the new ‘megas’. National’s health spokesperson Shane Reti has welcomed the report’s approach to addressing equity but has rejected reducing the number of DHBs.

The status of the proposed Maori Health Authority provides insight into who drove the review and its approach. Officially the review was the work of a panel comprising a number of capable respected people from the health sector. A majority favoured the Authority having stronger powers in commissioning and funding decisions, but they were overruled by review chair Heather Simpson. Simpson’s remarkable statement to NZ Doctor essentially justified this by saying that just because it was the majority view, that didn’t mean it was the final view. This experience is the source of disgruntlement among several panel members. Consequently, the final report should be called the Simpson report rather than the review panel’s report.

Why the Simpson Report fails

“I’m here not to let you be contented with too little.”

William Morris

The more I read the Simpson report, the more I’m dismayed, and the more I’m reminded of these words of William Morris back in the 19th century – This approach has informed my writing methodology for some time, initially subconsciously but now consciously.

The difficulty with analysing the report is that there is insufficient explanation or evidence for what it proposes – especially in respect of the massive restructuring plans – other than the self-evident observations that there is a pressing need to significantly improve equity and national cohesiveness. There is no dispute over how pressing this need is. But a key failing of the report is that it never explains how its proposed restructuring would address this need.

Failure by the report to explain or justify this restructuring contributes to its lack of due emphasis on the health system being sufficiently resourced to provide patient-centred care. If health professionals had sufficient time to provide patient-centred care, including time for good conversations about treatment and other options, then not only would the quality of their care improve, but so would its cost effectiveness.

Similarly, the report’s failure may be responsible for the omission of a good discussion on how important investing in the health system is for improving economic performance in developed economies such as New Zealand. This omission is surprising, as the correlation between investment and economic permance is internationally recognised by many studies and authorities such as the International Monetary Fund (far from a socialist organisation).

Structural vs Relational Approaches

Overall the report fails because it adopts a structural rather than relational approach to designing a more effective and sustainable health system. Structural change invariably lacks insights into the drivers of performance and non-performance and at best focusses on symptoms (more often on pre-determined positions) rather than causes.

Relational change, on the other hand, recognises that health systems are of necessity labour-intensive and based on a highly trained workforce. Utilising this capability through relationships based on robust engagement means that change is much more likely to be effective and therefore sustainable. The report’s structural lens leads it to ignore or diminish necessary priorities, and makes it weak in several key areas. Ultimately, this structural approach also means that if endorsed by the next government without fundamental changes, the report would lead to an adversarial leadership culture within the health system.

Social determinants of health

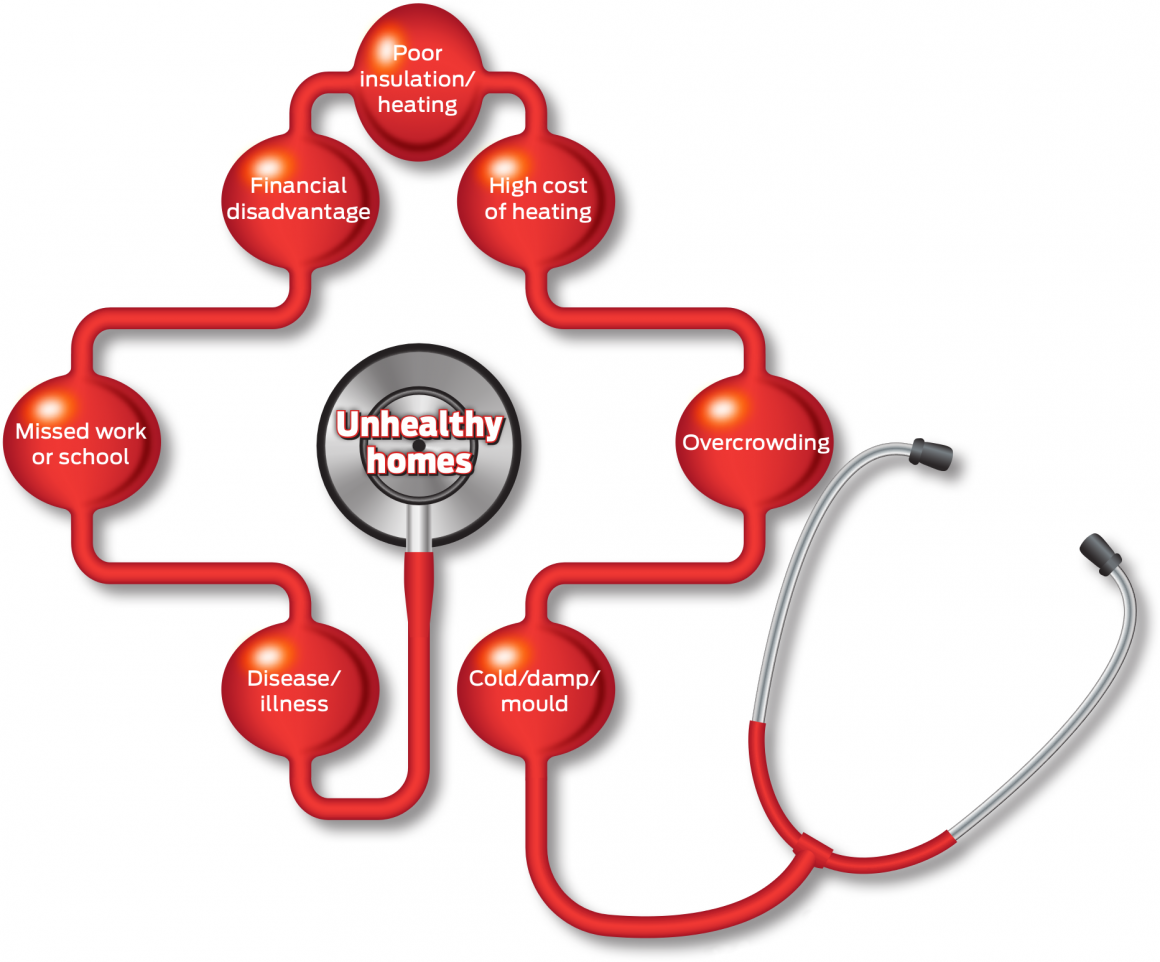

If the Simpson report fully appreciated the nature of the challenges faced by our health system it would have commenced with a focus on the imperative of addressing social determinants of health and what the role of the health system in response should be. Social determinants drive health inequities more than anything else, at least outside of mass health emergencies such as pandemics.

Former PM Helen Clark has noted that her work as Housing Minister did more for the health of New Zealanders than her work as a Health Minister. Her observation is consistent with the accepted recognition that overwhelmingly social determinants external to the health system, in fact, drive much of the demand placed on the system. Key factors include housing access and quality, educational opportunities, environmental factors, occupation, income level, food insecurity, racial discrimination, and gender inequity.

The biggest positive impact on the health and wellbeing of New Zealanders would eventuate if these social determinants were significantly reduced (or preferably eliminated). How the health system can contribute more to addressing this challenge is a question the review barely recognises. Rather than a substantive narrative on the topic, there are only six brief references such as data collection to social determinants, essentially reducing them to bullet points.

What is the point of having a review of the health and disability system if the main drivers of illness are ignored? Social determinants of health should have been the opening theme of the report which could have then discussed how the health system might operate both nationally and at a DHB level to reduce them. Increasing capacity and capability for an expanded role for health protection services would be a starting point.

Unmet need

Social determinants of health are the main drivers of illness. One of the main outcomes of these and other drivers is a high level of unmet patient need. A conservative preliminary estimate is that the rate of unmet need is about 9% of the population. But both the former National and current Labour led governments have been disinterested in pursuing this research further.

The Simpson report does give more recognition to unmet need than that given to social determinants. But it still isn’t given the priority it deserves if there is to be a genuine commitment to addressing it. There are 12 brief references to unmet need in the text of the report. In so far as they go these are useful.

However, while important, the main focus is on unmet need in primary care. This includes community based locality planning and service networks. But the high level of unmet need for hospital diagnosis and treatment is not addressed. Overall the combination of not being a more important part of the report’s narrative and the neglect of hospital unmet need is a major failing of the review.

Role of workforce engagement

The report does recognise the importance of the workforce and acknowledges the pressures placed on health workers. But it doesn’t recognise sufficiently the centrality of its role. There are 3 main things responsible for driving innovation in health – a highly skilled workforce (a primary driver as healthcare is labour intensive), technology (essential as an enabler and efficiency saver for this workforce), and an engagement culture (creating greater opportunities for continuous quality improvement to flourish).

The most critical part of the health workforce are those involved in clinical, diagnostic and public health work. They are the ones, more than others, who have the capability to improve the quality and financial performance of the health system. They comprehend the complexity of the health system. They possess the wherewithal to problem solve and address systemic challenges. Two things are required to achieve this – capacity (ie, addressing severe shortages) and an engagement culture giving oxygen to the capability of this potential pool of human creativity and capital.

The report is not discursive about this exciting potential. Further, it doesn’t question the dominance of the opposite culture of managerialism in the Health Ministry and DHBs in which management or bureaucracy is the driver and controller rather than a supportive enabler.

Ignoring inconvenient truths

The highly structural lens of the Simpson report is evident not only in its focus on major restructuring as the means to achieve its ends, but also in its rigid use of tiers – Tier 1 for primary care and Tier 2 for hospital care. This narrow lens leads to a failure by the report to consider the dynamic of the continuum of care between community and hospital, including its ongoing interactions.

An example of the missed opportunity here is the failure to address innovative solutions such as the clinically developed and led ‘HeathPathways’ pioneered by Canterbury DHB and recognised internationally as a success. HealthPathways (which includes an online manual and community platform) has successfully bent the rising curve of acute demand, which both saves millions of dollars and is difficult to achieve because of the combined effects of increasing aging of a growing population and poverty-related illnesses. Ignoring this successful approach suggests an unwillingness by the review to consider approaches that don’t fit in with a pre-determined paradigm.

The review’s disregarding of the success of HealthPathways also might reflect the tension that has led to the meltdown of Canterbury DHB’s leadership. The more engaging leadership culture that did the Canterbury population so well after the earthquakes, other natural disasters, and mosque killings fell victim to a bureaucratic coup from central government.

Acknowledging the success of CDHB’s engagement approach would have done the report writers no political favours. This omission suggests a propensity for the Simpson report to ignore inconvenient truths. Its silence on the experience at South Canterbury DHB where the Primary Health Organisation was disbanded suggests another inconvenient truth to be ignored. Disbanding the PHO was in response to its poor relationship with its 27 general practices and their PHO.

Essentially the problem was a middle entity positioned in a way that obstructed good engagement between SCDHB and local GPs. To solve this problem the PHO was dissolved and SCDHB and the general practices set up their own fit-for-purpose engagement process. This new process led to much improved relationships. SCDHB took over the statutory functions such as funding and population analysis that the PHO had undertaken through a management company. Relationships between general practice and the DHB significantly improved.

The initiative was helped by the smallness and compactness of SCDHB’s defined geographic population. It meant that primary care funding was better protected including not being top-sliced for other purposes. It also involved using the hospital emergency department to relieve the pressure on GPs after-hours including weekends.

The South Canterbury experience is the closest example to the locality planning recommended by the Simpson report with the qualification that it is confined to general practices and the DHB because it wasn’t able to extend further.

Remarkably the Simpson report doesn’t discuss the experience as a starting point for locality planning. A successful experience in a small DHB can’t form part of the report’s narrative because it is an inconvenient truth in the face of its advocacy of mega DHBs as a means to achieving greater centralisation of decision-making.

Increasing centralised decision-making

The Simpson report’s way forward is to recommend increased centralisation through the creation of both ‘mega DHBs’ and an additional powerful new national health bureaucracy. This restructuring would enable increased top-down decision-making and reduced community and workforce engagement and voice in the health system.

Mega DHBs

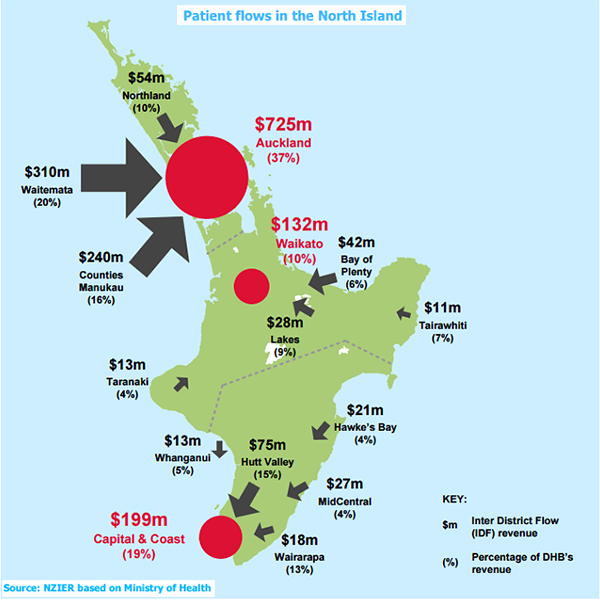

The report recommends that over five years, the number of DHBs be reduced from 20 to either 12 or 8. If the number were to reduce to 8 mega DHBs then most likely they would be centred in Auckland with three there, and one in each of Hamilton, Palmerston North or Hastings, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin.

If the most important form of coordinated service provision is between DHBs then these ‘megas’ might make sense. But this logic suggests that coordination would only be between hospitals. However, the more critical coordination and integration is between community and hospital care. This is where effectiveness and innovation is best able to improve the health system’s capability to contribute towards reducing social determinants of health and unmet need.

A strength of DHBs is that they are responsible by statute for the healthcare of defined populations within their boundaries, from community to hospital. It creates a construct for enabling integrated care based on a focus on the continuum of care between community and hospital. But the continuum depends on effective general practice voice and engagement with their relevant DHB. By moving to a small number of centrally controlled ‘mega DHBs’ the distance between general practices and decision-makers increases.

To make it worse, the Simpson report would have DHB health professionals, managers and other staff be subjected to 5 years of unnecessary distraction and disruption without providing evidence as to the supposed ultimate benefit.

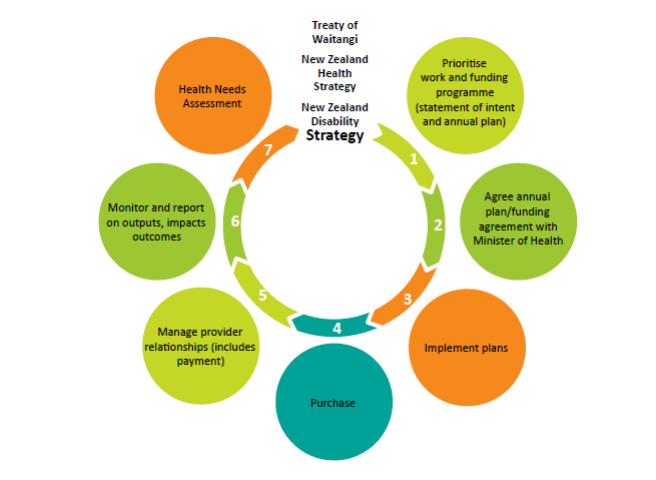

Creation of Health NZ

The second part of the recommended more centralised structure is the creation of a new powerful national bureaucracy (provisionally named Health NZ) to sit alongside the Health Ministry. Health NZ would be responsible for the funding and delivery of health services to the whole health system and for its outcomes. The new ‘mega DHBs’ would be required to Implement its decisions. In other words, Health NZ would tell these DHBs what to do. This includes what services are provided, where they are provided, and how they are provided within their greatly enlarged boundaries.

The capability for this increased central control would be strengthened by the new Public Service Act 2020 (replacing the State Sector Act). It incorporates several crown agents including DHBs into the public service giving their chief executives the same accountability requirements as those of government departments. DHBs would shift from being a form of local government to, in effect, being parts of a government department. This will make it even more difficult for DHBs to advocate for the health needs of their population.

The review is saying that the Health Ministry doesn’t have the capability to address the challenge of cohesion in our health system. Rather than advocate for the Ministry to establish this capability, it instead goes down the path of creating a new additional bureaucracy with all the scope for bureaucratic tension and transaction costs this entails.

A failure to learn from history or international examples

Unfortunately, the review forgets New Zealand’s own history in forming additional national health bureaucracies. In the late 1990s we had the ill-fated and short-lived Health Funding Authority in conflict with the Health Ministry. In 2009 then Health Minister Tony Ryall rejected a proposal to establish a second national bureaucracy largely on the grounds of cost.

Further, in citing Finland and Norway as overseas examples of their new national structure proposal, the review gets its facts wrong. Neither country has the equivalent of Health NZ and in fact, both their health systems are more decentralised than New Zealand’s presently is.

Removal of local voices

The input of community and health professional advocates is critical for the effective functioning of a health system. It is a form of self-generating empowerment that enhances understanding and performance. Simpson’s restructuring would lead to the muting of this voice because of the increased distance of centralised decision-making.

The removal of elected Board members would have a similar effect. Elected members are being unfairly blamed for past failures in order to justify a new centralised regime. Overwhelmingly DHB disasters have been due to the poor performance of politically appointed board members, particularly chairs. Examples include the IT fiasco at Capital & Coast over 2 decades ago, the appointment of disgraced Waikato chief executive Nigel Murray, and the most recent leadership meltdown at Canterbury. There is no evidence that elected board members generally are less competent than political appointments. If anything the voice of elected representatives has been smothered by the current system.

The end result of Simpson’s restructuring would be that decision-making that directly affects communities would be made much further away from them than is presently the case. Especially when seen in the context of the Health Ministry’s successful assault on Canterbury DHB, the most likely outcome of the Simpson restructuring would be a centralised authoritarian leadership.

Dousing the glimmer of locality planning

One effect of Simpson’s restructuring would be to douse one of the few positive features of the report – the introduction of planning by localities that might be based on local government, natural border or iwi boundaries. The attractive glimmer of locality planning is that it would include important work such as health needs assessment, unmet need assessment, considering what services should be provided, new network services, and clarifying expected outcomes across the area. Each locality would have an indicative budget based on the age, ethnicity and deprivation of its population and would establish service networks.

With the population data analysis and management functions currently undertaken by PHOs (which would become redundant) transferred to DHBs, locality planning might have good potential. But effective locality planning requires unimpeded community voice. The more ‘mega’ the DHB, the further the distance between decision-makers and the community voice and consequently the greater the impediment to that voice.

Cohesiveness and Equity?

It was hoped that the Simpson review would provide a blueprint for the future development of our health system that would build on its strengths and address its weaknesses. Simpson identifies two main objectives – improving national cohesiveness and equity. But the reality is top-down control simply doesn’t deliver either.

Instead, we have been left with a muddy footprint for a top-down bureaucratic approach to guiding autocratic decision-making at the expense of public and health professional voice. How else can we understand a report that clearly doesn’t understand itself?

Take Action: A Survey on Improving Public Health in NZ

Comment on This Article Here

Take Part in the Transition

The ScoopCitizen ‘engaged journalism’ service provides a safe and deliberative members-only ‘engaged journalism’ space.

ScoopCitizen is a place for learning, discussion of ideas and collective action using ScoopCitizen tools via our partnership with GovTech startup NextElection and engaged journalism methodology.

This is an attempt to bring more participation and engagement with you, our readers into the process of creating quality journalism.