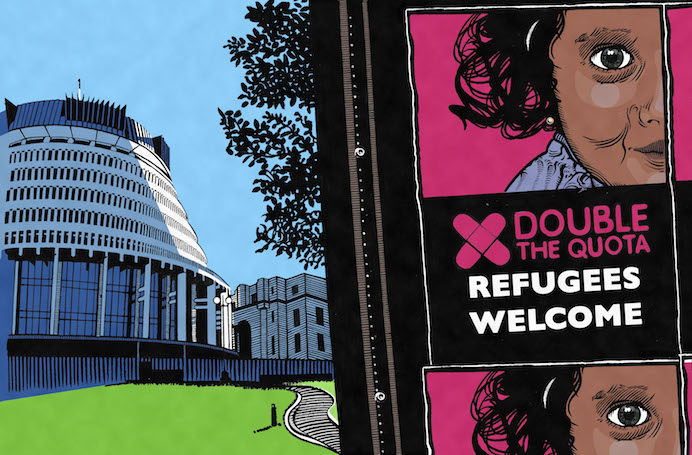

The refugee quota got doubled, but what can be done in a COVID-19 world? Three important refugee topics for the 2020 election.

You may be forgiven for thinking the refugee issue is of a low priority given the current global circumstances and our closed border policy. However, the issue has not gone away for those in need of asylum or refuge, and the moral imperative has not disappeared for New Zealand as a relatively stable nation. In fact, those living in refugee camps are among the most vulnerable communities to the impacts of Covid-19. In such precarious and challenging times, there is arguably even more need than ever right now for us to stand up for humanitarian issues: for if we only accept refugees in the best of times, what does this say of our commitment to human rights?

What is in place, and what is being discussed?

Of the parties represented in Parliament, only the Greens have released a policy that deals with refugee issues. Compare this to 2017 when every party had at least some position on what the quota should be and how we might get there. The Greens’ pledge to progressively grow the annual resettlement quota to 5000 places is reminiscent of their 2017 pledge, but without the detail on how much of that would be community sponsorship (1000 community sponsorship; 4000 general quota) and what time frame they would aim for (six years in 2017).

While the actual quota numbers were a big issue at the last election, the agreement of the coalition government to increase it to 1500 as of this year has led to many party’s positions becoming outdated, with no serious party explicitly campaigning on cutting that number. Judith Collins has said that number is about right. Given that Covid-19 has meant the policy has not been implemented yet, we’re likely to see more discussion on when the humanitarian side of immigration policy will open up, rather than on the size of that intake.

At the budget there was a raft of new commitments on refugees with an extension of family reunification, the community sponsorship pilot, security at the Mangere Refugee Resettlement Centre and increased processing of asylum claims. These were passed by the coalition government, though the family reunification review was a product of the confidence and supply agreement pushed for by the Greens.

The only thing that has broken the silence on these policies – silence being golden or ominous depending on your perspective – has been the potshots taken around Behrouz Boochani’s accepted asylum seeker claim. Those criticisms may indicate a broader disposition against asylum seekers by National and NZ First, but they also indicate that those parties have been studying the conservative political successes of the Australian Liberal Party and the Tory/UKIP dominance in the UK. Luckily for the quality of the political discourse in Aotearoa New Zealand, there is little replicable about their border experiences and politics that would work on these shores.

The issues we should be talking about

I’ll expand on what I believe are the key issues in the refugee sphere below, in the hope that there will be some discussion of them rather than not.

Of course, in some cases it might seem better to not talk about humanitarian support when there are so many challenges facing the world. Some might make the argument that these discussions are best left to policy specialists in Immigration NZ as the complexity of them tend to inflame the public and politicians who think they can score points off of these issues. While not talking about these issues for fear of what might be said may occasionally be the best strategy, ultimately the silence around refugees and humanitarian issues will be filled by those with the least progressive agendas.

To counter that, there is a need to start having some of these tough discussions. For example, it is worth noting that more than half of the people who apply for asylum are rejected and are deported. No-one likes the idea of deportation, but the only way to ensure it functions is to emphasise that this immigration channel is solely for those fleeing persecution.

If we don’t have discussions on these issues we end up with the void that allowed the conspiracy theories around the UN Migration Compact and the ease with which the opposition National party amplified lies about the impact of that agreement. Just for clarity’s sake, the lie I am speaking of is National deputy leader Gerry Brownlee saying that we now had pretty much open borders in New Zealand because we’d signed the agreement.

With policies not forthcoming on this issue, there are three key areas where policy ought to be stated, but has not. (We have asked these questions to the political parties. You can help by sharing these questions on social media, and tagging your local representative to make them take notice. )

- Where does our humanitarian intake sit in the hierarchy of immigration?;

- What support will help resettled refugees’ voices be heard?;

- How will asylum seekers – both those who have just made a claim and those who have been accepted – be treated?

Where does our humanitarian intake sit in the hierarchy of immigration?

First, Covid-19 has closed the borders to all but NZ residents and citizens. Prior to the recent outbreak and return to some forms of lockdown, the Prime Minister had indicated that in the coming months migrant workers in essential industries would begin to be welcomed back into the country. Opening these spaces to non-residents was, she noted, dependent on space opening up within New Zealand’s 7000 quarantine places.

For some context, it is worth noting that the 1987 Immigration Act is the basis of the contemporary immigration policy. Back then the discussion centred on an aim for 90% of new migrants to be welcomed based on their skill and the remaining 10% to humanitarian. The humanitarian stream includes groups of various Pacific visas (like the Samoan Quota and Pacific Access Category) which are not refugee categories. The processing of these visas have been halted along with the refugee quota programme. It’s also worth noting that the refugee quota can be housed at the Mangere Refugee Resettlement Centre and isolated for two weeks, as with the final intake in March before lock down.

The only things slowing down the return of refugees to New Zealand at this time are on the leaving end: can refugees get on flights to come to New Zealand? Can the UNHCR offer final preparation before departure? It is worth noting, also, that our quota operates in a long pipeline and there are people who have been told they will come to New Zealand, but who are waiting.

Given this background it is worth asking our political parties:

What support will help resettled refugees’ voices be heard?

Second, there have been numerous questions – both before the mosque attacks in Christchurch and after – about which voices are given most priority in the New Zealand media. While New Zealand’s refugee quota is made up of a wide range of religious and non-religious groups, all of them are establishing themselves in a new country where representation of their voices are scant. While Golriz Ghahraman became the first refugee-background MP in New Zealand’s history in 2017, and Ibrahim Omer seems likely to join her based on present polling, there remains a need for an elevation of refugee-background people’s voices.

The good news is that we have established organisations in the main centres that function as an umbrella for these voices: established in the first decade of the century, groups like Changemakers Refugee Forum work to represent the voices of all the ethnic communities in a resettlement location. The challenges ahead are multiple: the need for these organisations to develop stronger voices in the media, especially when post-mosque attacks they are being more regularly called on to do so; and the need for these groups to mentor and create similar organisations as new resettled communities are formed in the five new resettlement locations.

More broadly we also need to consider why there were only five new resettlement locations rather than six: the answer being in the failure of the government to genuinely consult with iwi in Whanganui. There is much unexplored space alongside lifting resettled refugee voices to seek out resettlement opportunities guided by whanaungatanga and manaakitanga.

Given this situation, it is worth asking our political parties:

How will asylum seekers be treated?

Third, the least represented and supported group of refugees in New Zealand are asylum seekers. In most of the world, the asylum seeker process is the main way that people receive protection. A person arrives in a country, makes a claim under the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees that they are, or fear being, persecuted. The state determines whether it agrees with this and either accepts or rejects their claim, with various appeals processes available in various countries. We all know how isolated Aotearoa New Zealand is from the rest of the world and this means there are few ways – especially with enhanced screening of passengers on airplanes – for asylum seekers to get here and make a claim in the first place. Last year just over 500 people made a claim for asylum and about 200 of these were accepted (once appeals were included).

Currently, asylum seekers are excluded from most of the resettlement support granted to quota refugees. Periodically, including in this year’s budget, the government allocates funds to speed up the process, but inevitably asylum seekers are in limbo for months before a case is heard and decided upon. There is also a disturbing trend of using prisons to house asylum seekers while their cases are being heard, leading to some truly horrific situations, including one person being forced into a Fight Club situation. And even when people are accepted they aren’t given access to the same support to settle as quota refugees. There’s a long running campaign from the Asylum Seeker Equality Project to offer that same support to asylum seekers.

With that context in mind, parties should be asked:

About The Author

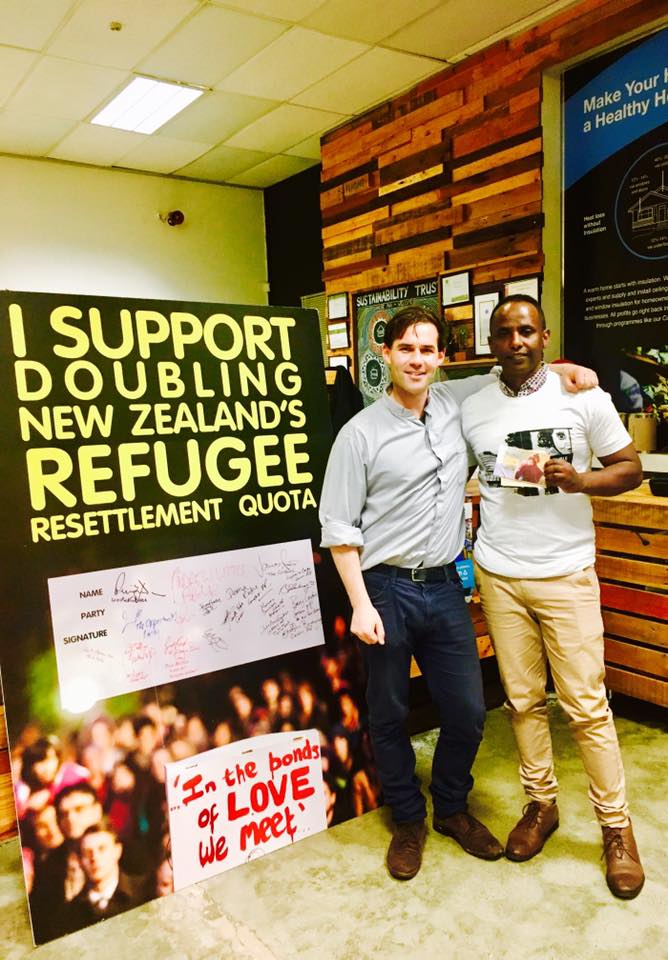

Murdoch Stephens founded the Double the Quota campaign to grow the refugee quota from 750 to 1500 places. This policy was put into effect on 1 July, 2020. He is also the author of Doing Our Bit: the campaign to double the refugee quota and the novel Rat King Landlord.

Take Part in the Transition

The ScoopCitizen ‘engaged journalism’ service provides a safe and deliberative members-only ‘engaged journalism’ space.

ScoopCitizen is a place for learning, discussion of ideas and collective action using ScoopCitizen tools via our partnership with GovTech startup NextElection and engaged journalism methodology.

This is an attempt to bring more participation and engagement with you, our readers into the process of creating quality journalism.

Sign up to ScoopCitizen now to stay tuned and participate as we develop the conversation on the Transitional Democracy series.

If you want to support us to expand this conversation and bring on even more great journalists to cover these CitizenDesks please setup a one-off or regular donation to ScoopCitizen via Press Patron. All funds raised will go to creating more quality content on this issue.