There is no energy crisis, only a crisis of Ignorance.

R. Buckminster Fuller

Energy is fundamental to life on Earth – without it, there would be no heat, food, motion, information, or life. All our core needs such as feeding and raising families, running businesses, and pursuing our recreational and social lives on and offline demand energy use to some extent. Our civilisation is driven by a seemingly insatiable eternal growth economic paradigm which leads to a constantly increasing demand for energy and expanding land and resource use.

However, generating energy from our environment generally has negative impacts on the natural world. In fact, evidence suggests that our expanding needs are pushing up against the hard biophysical limits of the planet’s capacity. In that case, can a steady supply of energy be taken for granted while maintaining the lifestyles and protecting the natural abundance we value as a nation?

Energy is Politics.

“There are deep links between available energy and the very structure of civilizations, including their types of social organization and levels of complexity.”

Anthropologist Leslie White

Energy production and control was central to the emergence of the earliest human societies, and is still integral to our complex modern civilisation and to our wellbeing. Up until a few centuries ago, energy mostly came from the solar energy trapped in firewood or draught animals. Since the industrial revolution our modern society has been mainly powered by the cheap and abundant energy of fossil fuels like coal or gas which effectively store captive solar energy as carbon in the earth.

As we learn of the downsides of carbon emissions, energy is now increasingly being generated by harnessing abundant natural forces such as the sun, wind, tide, hydro or geothermal energy, along with other emerging technologies.

However, regardless of the source, the control of energy generation resources, tools, and systems invariably equates to political power, making it a key aspect of the nature of our political and social systems. The questions of who controls our energy supply, and who gets to decide what energy sources we use, are inherently important to us all.

Our highly complex and interconnected technology-based global system requires significantly more energy to operate than any other civilisation in history. This system is by far the largest, most technologically advanced collection of built capital, supporting infrastructure, expertise, and organisational capacity that has ever existed.

We have extended our day into the night – our entire system is built upon near constant energy consumption. Our homes, offices, and recreational activities require electricity for their construction, for lighting, temperature control, and now for an ever-growing array of smart features. New Zealanders are, in fact, amongst the highest global consumers of energy globally. Our primary energy use per capita in 2019 was 191 GJ ( vs a global average of 76 GJ). (BP Statistical Review)

But what if this level of energy use was no longer possible?

The Energy Transition

Many energy experts have suggested that the current social, technological, and economic arrangements we enjoy today in New Zealand and the rest of the ‘global North’, are likely unattainable at significantly lower levels of energy consumption.

But, whether we can continue to produce the amounts of energy required without continuing the environmental degradation and climate heating taking place today is now in serious doubt. The IPCC has scientifically established a causal link between climate heating and the rapid growth of emission-heavy methods of generating energy to power our houses, cars, and industrial infrastructure supporting our economic and food systems over the past century. Urgent change to this system is needed globally to avoid the worst effects of this overheating.

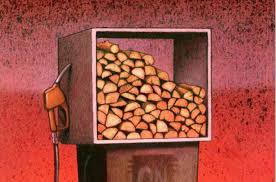

Leading energy science also indicates that the era of cheaply extracted and produced fossil fuels is over. Energy scientists, economists, and engineers are increasingly warning of the fact that we may be reaching ‘peak energy’ Even the fossil fuel giant BP has now accepted that the world has already passed Peak oil. The Energy Return on Investment (EROI) conundrum means it now costs more to extract fossil fuels than the energy they provide. Some, such as Jack Santa Barbara writing for this series on The Dig, even point to a possible reality of depletion – or a decline in overall net availability of energy known as ‘Energy Descent’. The reality is we may well have less energy available to consume in the future than we do now.

Despite the hype around renewable energy, today’s overall share of renewables in meeting global energy demand is relatively minor. It is expected to grow by one-fifth in the next three years to reach 12.4% in 2023.

Some leaders put faith in ‘salvation technologies’ to escape these challenges, but many energy engineers and scientists believe that even the brightest of these emergent technological prospects are too far off in the future to affect this troubling equation.

Even if some miraculous technology emerges, the disruption of nature will not end without change to the operating rules of the current growth at all costs world system. The more energy we have, the more likely it is that humanity will continue to expand and destroy and disrupt natural systems through unsustainable land-use. Having abundant clean energy without better local and global environmental governance and regulation could thus be terrible for the planet and its biodiversity which is already facing mass extinction. This will also seriously impact our wellbeing as a species as we are intricately connected with natural systems and with other species.

Like it or not, an energy transition is happening now, and is an urgent priority. The way we plan for, prepare, and go about this, will determine whether the transition will be a catastrophic disruption or a positive opportunity for social transformation. For that reason, we believe it is an area in which we should hear from as many voices as possible in making decisions around future policy in this area.

Energy Resilience: Central to Wellbeing

Wealth is the product of energy times intelligence: energy turned into artifacts that advantage human life.

R. Buckminster Fuller

The many methods of harnessing energy for our uses vary in efficiency and all require different combinations of inputs of energy, financial investment, and other materials. New Zealand is fortunate to have already invested heavily in building up a relatively high mix of renewable energy in the form of hydro (~64%), geothermal (~18%), and wind (~5%). Once built, these energy sources have relatively low carbon emissions, however, we cannot afford complacency as this does not mean we have an entirely resilient or sustainable system – there are still many risks and costs involved.

We have a centralised and technically complex system for generating and getting electricity from A to B which often means a long distance between hydro schemes in the South Island to the main population centres in the upper North. Our transmission system is vulnerable to disruption by natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions or disruptions to hydro flows by changing climate.

There are still carbon and financial costs involved in both maintaining our renewable energy infrastructure and transporting energy to where it is required. We rely heavily on fossil fuels sourced on the global market for much of the maintenance and transport costs of these renewable sources. Materials such as steel, concrete, battery storage, and electronic consumables, all derive heavily from the mining of rare earth minerals and other energy-intensive and extractive activities. Our energy-intensive industrial economy (which includes agriculture) also relies heavily on fossil fuels.

This means that currently, fossil fuels still underpin New Zealand’s renewable energy systems. Without this cheap energy source, the net energy produced by our renewables would in fact be much lower. As such, we are still reliant on the interconnected global energy web and supply chains, so are far from isolated from its precariousness.

Our reliance on this global system of fossil fuels and minerals also often places social and environmental burdens on the source countries. Most of these are sourced by colonial exploitation of the relatively poor and less politically powerful nations of the Global South. However, that situation is also likely to change as the hegemony of the Western liberal international order wanes in coming decades. This should be considered as a policy factor in addition to overall emissions and cost.

This overall lack of resilience in our energy system is not widely understood yet, and has not been acknowledged by our Government, or taken into account in their policies and planning for a transition to a mostly renewable-based energy system. However, it presents a real risk to our national wellbeing.

Energy Descent: Catalyst for Transition

Two challenges—climate change and the effects of depletion—will require action if we are to avoid economic, environmental, and social calamity.

The Community Resilience Reader: Essential Resources for an Era of Upheaval. The Post Carbon Institute.

The climate crisis has put energy firmly back in the public consciousness in recent years as it forces us to reconsider our approach to energy systems. However, an even more serious matter related to the climate crisis is emerging. This could properly be called an ‘Energy Crisis’ due to the human suffering it is likely to cause under the worst-case scenario. There have been events misleadingly termed ‘energy crises’ before, however, these have actually really been crises for capitalism and the oil-producing nations and corporations.

However, the crisis we imminently face is one relating to overall available energy to meet our needs – the crisis of energy depletion, or ‘energy descent’. This theory holds that global net energy available for human use looks set to begin to decline. The exhaustion of cheaply available fossil fuels means that there are hard limits on our ability to continue consuming energy to the extent we do today as a society. In other words, we will by necessity have less energy available as a society to utilise even when taking into account best-case scenarios for renewables. Given our society is on a seemingly unstoppable economic growth and land-use expansion path, this is a highly concerning matter. Jack Santa Barbara has explored why this issue of Energy Descent matters in detail for the Dig and Better Futures Forum here.

Understanding and responding to this energy descent problem is critical to the future shape of our human societies. A failure to understand and prepare for the necessary energy transition it entails is a threat to human wellbeing. Energy system failure or collapse has been a key factor in the decline and fall of many civilisations in humanity’s history, and we appear to be on course to repeat these mistakes. However, knowledge of this situation also presents a positive opportunity, as it will, by necessity, catalyse a system-wide transition of our society which could lead to better overall human wellbeing.

For this reason, rather than a crisis, a better term for this situation is the Energy Transition. We can see this energy descent imperative as an opportunity for a positive transition. It could act as a catalyst to accelerate the necessary transition to a new energy system and in fact an entirely new approach to approaching our national wellbeing.

Transition Scenarios

A positive scenario for this transition is only likely if there is a real commitment from those in power to a proper scientific and evidence-based discussion and consideration of solutions that may challenge the status quo of the liberal political and economic ideology. Currently our decision makers seem unwilling to have the difficult but necessary discussions this involves. Instead, like the early days of the climate crisis, they are taking an approach of ignoring this issue. As a result we are blindly continuing on a possibly calamitous path without considering viable alternatives.

With this in mind, here are two hypothetical scenarios. Which scenario our future as a nation more closely resembles will depend on how we as a society choose to think about and prepare for the necessary reality of the Energy Transition over the coming years.

The Current Trajectory Scenario

The current trajectory our society is on is to simply attempt to continue our high energy consumption lifestyles and focus on economic growth and a market-based approach to energy.

The approach now being planned for by Governments (including NZ) appears to be an incremental move from fossil fuels to renewables as a straight substitution.

Using fossil fuels to transition to a renewable system may be possible, but this will be adding to the amount we are already using, and will push the climate beyond 3 degrees Celsius – a dangerously high level. In addition, there are not enough of the required minerals to transition to a full replacement system of energy production on the scale we have today.

Under this scenario, powerful nations will continue to mine and burn up whatever fossil fuels can be extracted affordably to fuel economic expansion and increase land and resource use. There will also be a greatly increased risk of energy and mineral wars, including an already escalating threat of nuclear war as nations resistant to changing their internal energy infrastructure battle over dwindling fossil fuel resources.

Continued rising temperatures will continue to wreak havoc on global weather patterns – creating costly natural disasters, disrupting our intricately connected biodiversity and food systems, and ultimately lead to a collapse of global supply chains, and the international economy in stages. This will likely lead to the collapse of our entire civilisation and the global chaos of a race to the bottom.

If New Zealand does not forge its own path to a more resilient system, the outcome will be similar for us. However, there is currently little evidence that this possible scenario, or the energy descent equation are being taken seriously in future scenario planning by New Zealand parties.

The Planned Transition Scenario

Instead, if we are serious about our survival as a civilisation and ensuring widespread wellbeing, a planned transition scenario would recognise that we will likely need to make a major transition in our approach to energy as a society. This scenario would see our Government urgently start the process of planning and preparing for this transition by reconsidering our use and generation of energy at a more fundamental level.

Under this scenario the Government would recognise the need to urgently transition away from fossil fuels in order to avoid climate chaos, further pollution of our environment, and biodiversity loss. It would acknowledge that it will be increasingly challenging to ensure the continuity of the levels of technology and quality of life we have come to expect.

Large-scale electricity and fossil fuel developments would progressively be supplemented where appropriate by decentralised and localised energy sources and emergent energy technologies such as solar, small-scale wind, clean-burning closed system wood fuels, and biogas. Today’s economies of scale in energy supply would be supplemented by the economies of scope of local energy, which creates extra benefts in employment, management of ecosystems and regenerative agriculture.

In this scenario, our Government would also take a lead on much more integrated planning of our economy and society with a focus on wellbeing rather than material consumption and economic growth. This would involve honest and open communication with citizens and industry about the need to design an alternative strategy for ensuring people have the energy to meet their basic needs.

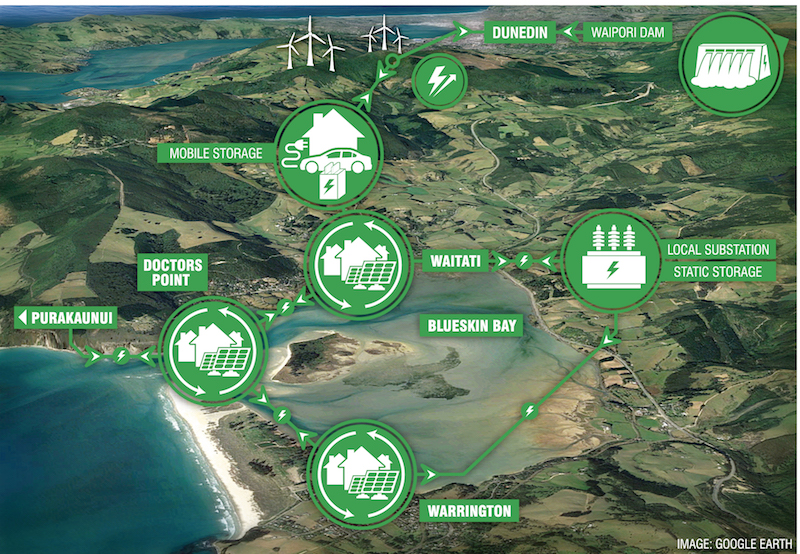

This redesign process would include a reimagining of our energy systems to focus more on local and cooperatively owned energy production and storage solutions rather than profit-driven centralised grid systems. This would be achieved by removing barriers and providing incentives and support for communities to take energy needs into their own hands.

However, even more crucially, this scenario would involve reimagining our industrial and agriculture systems and changing the way we plan for urban development. It would require changes to our transport habits and systems and our focus on what is necessary work. It would mean adopting innovations such as circular economies, 20-minute cities, better public transport, cycleways/walkways, more remote working and the creation of more local employment opportunities.

The society resulting from following this scenario would look very different from the one we have today in ways that we cannot even fully predict. It entails nothing short of a complete redesign of many of the complex systems running our society to reprioritise human wellbeing. Ultimately we have to learn to transition our entire society around the idea that we can still live well with less overall energy use.

Ensuring a Planned Transition for Aotearoa

“Overall, the transition will represent a trade-off between the costs of making a renewable energy system act essentially like the current one and the costs of adapting our energy usage patterns to the inherent qualities and characteristics of renewable resources.”

The Community Resilience Reader

In light of the gravity of this situation we find ourselves in, it is important for New Zealand as a nation to consider how we navigate the potentially troubling waters ahead and reframe this as an opportunity for a more sustainable and genuinely satisfying life.

The reality is that the biophysical limits of the planet simply can’t sustain the growth in energy and land/resources that our current trajectory of ever-increasing economic growth and expansion requires. The upshot of that is that we would need to learn how to live well without so much energy and move towards a society designed so that human activities and energy needs do not exceed the capacity of the environment to support it.

The Planned Transition strategy would be to effectively co-create as a society a more positive, inclusive, and resilient vision for what the priorities are for our energy system, and then work to redesign it along these lines. This window of opportunity is only possible if those in power urgently start the discussions needed around planning for a transition to a society based on wellbeing.

We need policies and leadership to catalyse this discussion urgently, rather than policies simply attempting to replicate our high consumption, growth-focused lifestyle with renewable energy sources. We also need clear leadership to increase energy literacy and understanding of the need for demand-side adaption in place urgently, If not, we could be setting ourselves up for the messy and destructive collapse of our entire global economy, ecosystem outlined in the first scenario.

The Transitional Energy Series

So how can we start the co-creation of a more positive vision of what is possible? This transition will require a radical reimagining of the way we generate, consume, distribute, store, and most importantly, think about energy in New Zealand. If we are truly to achieve such a momentous transition we will need to reconsider every aspect of our complex society, our economy, our social systems to ensure that the wellbeing of people is the central priority in the design of these systems. Most of all, this will also require a fundamental change to the way we do democracy as a nation.

A lack of democracy and undue influence by the corporate sector are the driving force behind our current approach to energy. A history of inaction by the liberal technocrats in our institutions in the face of extensive science on climate change and continued pandering to the lobbying of industry makes it clear they are likely to be unable or unwilling to make the hard choices needed to make the systems-level change needed to lead a transition in the energy sector.

We can no longer rely on representative politics to do what is right. Successive governments have allowed the market to determine how we used fossil fuels. If we continue to allow the market alone to determine our energy future, we are likely to create more messes. We must focus on designing alternatives to, or restraints on, the market as a distribution mechanism.

We cannot continue to allow our representatives to make decisions about our energy system that are not mindful, and inclusive, of the voices of the people affected by these decisions. Citizen engagement is therefore critical to determining our energy future. Everyday citizens must be actively engaged in this discussion and be given far more control over our local energy sovereignty and our goals as a society.

Community-led and partnership-based energy projects have shown great promise in driving more sustainable, and locally controlled cooperative energy production in places like Scandanavia, Germany, Scotland. Even here in Aotearoa, there are some notable examples such as Blueskin Energy a charitable Trust-owned energy company aiming to create a positive, healthy, secure, and resilient future for the communities of Blueskin Bay in Otago.

Such examples show that working together, we can build a better energy future. But ultimately, getting there will require that we have a map and common vision of where we are heading, and that we are all paddling the same waka, in the same direction.

The first articles in this Transitional Energy series are up now:

Jack Young has written a detailed analysis of the Green Party’s Energy Policy from a Transitional lens and has found many areas in which it does not go far enough. This analysis is available in a summary and a long version.

Jack Santa-Barbara has written an excellent article outlining the problem of Energy Descent which highlights why the next Government needs to take notice of this very real issue.

The Dig and the Better Futures Forum are running this Transitional Energy Series in order to address what we see as the major questions New Zealand faces surrounding energy:

- What does energy transition mean for the future of NZ’s energy system and our wellbeing as citizens?

- What should we be thinking about and doing in order to build a better future with abundant clean energy for all?

- How can we act now to ensure we become more efficient in our energy production and use?

- How can we reorganise our society so that we are more resilient to energy decline, or natural disruptions affecting our grid?

- Ultimately, how can we reorganise our society so that we stop our land use from impacting the overall stability and harmonious relations with other species?

Help us answer some related questions here:

Comment on the Transitional Energy Series here