In the global context of the 21st century, it is evident that the fates of all sovereign states are increasingly linked, and that smaller states like New Zealand must be prepared to become more active multilateral players.

Since the late 1980s, the world has entered a turbulent and prolonged transition to a new international order. This transition has been propelled, above all, by the demise of the Cold War and the impact of deepening globalisation.

In the post-Cold War era, the US was initially left as the world’s only superpower. But America’s ‘unipolar moment’ did not last very long.

Globalisation – the intensification of technologically driven links between societies, institutions, cultures and individuals on a worldwide basis – radically reshaped the economic, political and security landscape.

In many ways, the disastrous US-UN humanitarian intervention in Somalia in 1992-93 was a pivotal event for US foreign policy and the beginning of a road that ultimately led to 9/11.

The conditions that generated the Somalia crisis – civil war in a failed state – reappeared in a large number of other countries during the post-Cold War era, and contributed to a security environment in which transnational terrorist groups like al Qaeda and Islamic State emerged.

America’s extraordinary reaction to 9/11, starting with President George W. Bush’s ‘war on terror’, had far-reaching international consequences.

The US military campaign in Afghanistan from late 2001, and the invasion of Iraq in 2003 involved massive military expenditure.

However, this huge military spending was financed almost entirely by borrowing and that, in turn, helped generate the 2008/9 global financial crisis.

These events, as well as the ongoing Syrian civil war, dealt a big blow to America’s global standing and served to erode the legitimacy of institutions like the UN Security Council and specialised agencies like the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

For example, in a recent interview with Aaron Maté, the first Director-General of OPCW provided new insights into the way the George W. Bush administration sought to exert control over the organisation in the build-up to the Iraq invasion, which was then launched without the authorisation of the UN Security Council.

The post-9/11 period has significantly undermined the credibility of the international rules-based order (IRBO), and its ideas and norms such as neo-liberal economics, democracy, multilateralism and international human rights.

This system now faces serious problems of legitimacy and equity, particularly in the eyes on those living in the less privileged Global South. For a system based on rules to have effect, these rules must be visibly observed by their principal and most powerful advocates, and must work to the advantage of the majority and not a minority.

The Backlash

The backlash against the international rules-based order – sometimes called the liberal international order – has manifested itself in a number of ways as it faces a convergence of external and internal threats.

Authoritarian states like Russia and China have asserted their strategic interests in places such as Ukraine and the South China Sea at the expense of international law, and great power rivalry, particularly between the US and China during the first term of the Trump administration, has been reinvigorated.

In addition, a populist tide has swept through a number of states and has generated nationalist tendencies. Importantly this includes the US and the UK – the original architects of the liberal order.

The Trump administration has claimed the US is the victim of multilateral institutions like the WTO and withdrawn the country from arrangements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Paris Climate Accord, and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Meanwhile, the Johnson government in the UK “took back control” by signing a deal to leave the EU, a liberal democratic community of 27 states, but subsequently signalled its willingness to break international law by reneging on parts of the withdrawal agreement.

Allegations of Russian interference in British political events, including the 2016 Brexit referendum, led to a report by the UK’s all-party Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) in July 2020, which concluded successive UK governments had failed to investigate activities ranging from disinformation to the purchase of influence.

In the US, Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into alleged Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential Election generated more than 30 indictments, including key members of Trump’s campaign team.

A New Era of Interconnectedness

Nevertheless, and quite paradoxically, globalisation is accelerating. It is striking that during the lockdowns imposed by the current COVID-19 crisis the world has seen a massive expansion of digital networks in many fields, including healthcare, education and business.

There will be no return to the pre-globalisation era. The story of the post-Cold War era is one of growing interconnectedness, a context in which many of the challenges in the economic, health, security or environmental spheres can no longer be resolved by states acting alone.

Great powers can act unilaterally, but the results of such actions have been largely unsuccessful during the last three decades.

The US invasion of Iraq in March 2003 was a strategic and economic disaster for Washington;

Russia’s intervention in the Ukraine in 2014 left Putin’s regime diplomatically isolated in Europe and cost Moscow more than $150 billion in capital flight; and

China’s construction and militarisation of artificial islands in the disputed South China Sea region rattled their neighbours and prompted South Korea and Japan to bolster security ties with the US.

Today’s great powers have less autonomy and are more vulnerable than their counterparts of the past.

This is the international transition we are living through. It is characterised by an uneasy co-existence between the forces of fragmentation and integration. The trajectory of change in the future is towards a multipolar world, but it is an uncertain journey ahead.

What does this international transition mean for the newly re-elected Labour government led by Jacinda Ardern?

New Zealand’s Foreign Policy Challenge

Foreign policy must assume a much more prominent position in the government’s thinking.

It is clear that New Zealand’s national interests critically depend on an functioning international rules-based order, and that order is now under attack from a variety of sources.

It is also evident that traditional allies like the US and UK – currently led by populist nationalist governments – can no longer be relied upon to provide leadership in a multilateral setting.

Since 1945, New Zealand has been a firm supporter of the international rules-based order and its preferred instrument, multilateral diplomacy.

For New Zealand (and many other states) multilateralism provides a voice and influence on international issues that it cannot achieve on its own. And that is crucial for a country that is a global trader.

Despite having a relatively small economy, exports of goods and services constitute about 28% of New Zealand’s GDP, and Wellington has relied on the WTO’s comprehensive rules for regulating trade.

So New Zealand must now take steps to work with other like-minded states to build a new global grouping that is dedicated to defending and strengthening the international rules-based order (IRBO).

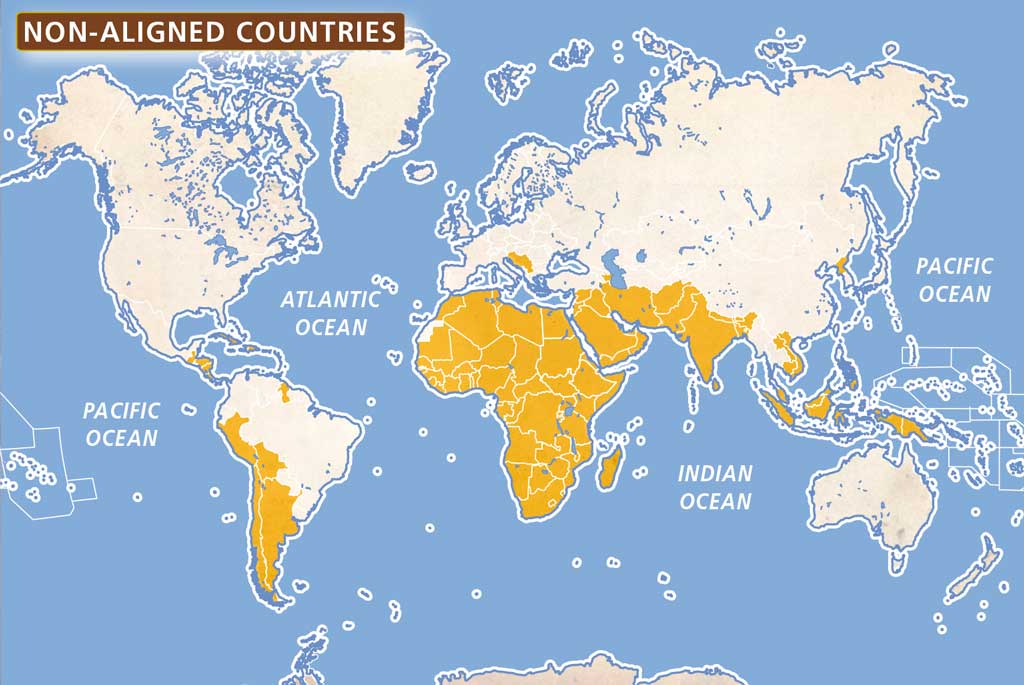

There is the precedent of the ‘Non-aligned’ movement established by developing states during the Cold War that may provide something of a template for the current era.

However, to take on such a more active international role, New Zealand’s decision-makers will have to start thinking of the country as a minor power rather than a small state.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern is in a good position to reset New Zealand’s foreign policy. In an interconnected world, the Prime Minister has deservedly won global admiration for her compassionate and decisive leadership in response to both the Christchurch terrorist atrocity and the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important that Ardern uses her international political capital to advocate for a bottom-up, strategic form of multilateralism that does not rely on great powers setting the agenda.

Much needs to be done. Constraining or abolishing the veto power of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and reforming the global economic system are among the reforms urgently needed.

We live in a world where inequality, conflict, pandemics and the looming threat of climate change show no signs of abating, so it is imperative we enhance the international means for addressing problems like these, which know no borders.

However, the transition to a more cooperative and inclusive world is not a foregone conclusion. It will take active input from New Zealand and other smaller and middle powers to fill the existing vacuum in global leadership and to help make it happen.

Robert G. Patman is a Professor of International Relations at the University of Otago