Next up – NZ First. Down in the polls this time around, Labour’s current coalition partner NZ First were the kingmakers last election. So, how might NZ First influence the next Government to address housing issues and improve Māori housing outcomes? Te Matapihi provides a perspective.

NZ First released their 2020 Policy Manifesto without fanfare the night of Thursday 2 October. Most of the items are captured by the party’s Housing policy, with some additional items under NZ First’s Strengthening Communities, Infrastructure, and Immigration policies.

The policy promotes home ownership and quality housing as the foundation for equality in New Zealand society, and proposes a number of practical interventions, including rebalancing the economy away from speculation, more targeted immigration and re-settlement policies, and a programme of legislative reform, including changes to the Resource Management Act 1991, the Building Act 2004, and the Residential Tenancies Act 1986.

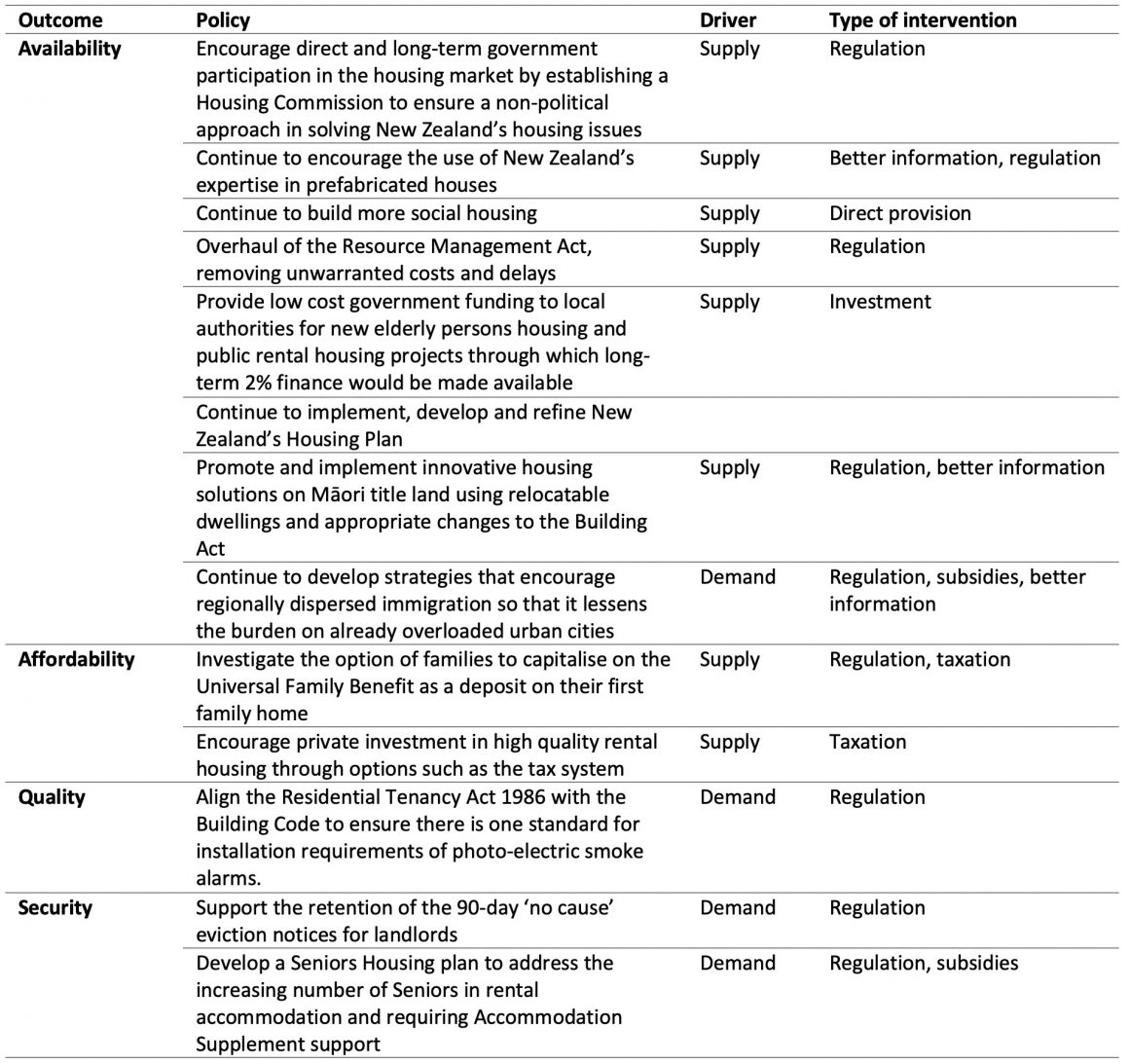

Table 1. NZ First’s Housing Policies – Summary

There are many interesting policies here, and some with real transformative potential. We’ll be unpacking the following in detail –

- Provide low-cost government funding to local authorities for new elderly persons housing and public rental housing projects through which 2% loan finance would be made available

- Investigate the option of families to capitalise on the Universal Family Benefit as a deposit on their first family home

- Promote and implement innovative housing solutions on Māori title land using relocatable dwellings and appropriate changes to the Building Act

1. Low-cost funding to local authorities for new elderly persons housing and public rental housing projects + 2% loan finance

The social housing reform programme initiated in 2011 saw the ability to access the Income Related Rent Subsidy, which was previously reserved for the former Housing New Zealand Corporation (now known as Kāinga Ora) extended to Community Housing Providers. The subsidy enables providers of low income housing to access a subsidy in exchange for providing housing to low income tenants, which effectively ‘tops up’ affordable rents (indexed to income and paid by the tenant) to market rates (with the difference paid by government).

The reforms, critically, excluded local authorities (with eligibility restricted to non-government organisations), many of whom offered low-income and pensioner housing. In 2016, Wellington City Council partnered with the Salvation Army to offer income-related rents to low-income tenants, the first time the subsidy was offered through council housing. Previously, Wellington City Council – as with other local authorities – had calculated rents as percentage (in this case, 70%) of market rents (with no subsidy available to cover the shortfall). This was due to Wellington City Council leasing the properties to the Salvation Army (the registered Community Housing Provider).

According to 2017 estimates, 15,300 (of a total of 83,300, or 18% of all social housing units) were not receiving income-related rent subsidies, and of these 7,700 (or 9.2% of all social housing units) were Council-owned units.

Will it work?

The social housing reform programme has seen many local authorities divest of their housing stock to Community Housing Providers and the private market (including the sale of 344 Hamilton City Council Units to Accessible Properties in March 2016m, the leasing of 2,250 units by Christchurch City Council to council-owned Ōtautahi Community Housing Trust in 2016 and the long-term leasing of 1,452 units by Auckland Council to Haumaru Housing – a limited partnership venture with the Selwyn Foundation). It is unclear whether the policy intends to amend the Social Housing Reform (Housing Restructuring and Tenancy Matters Amendment) Act 2013 to extend eligibility to local councils, or if a separate programme and funding stream is proposed.

Advocates and local councils have long called for the extension of the income-related rent subsidy. Many Councils are significant providers of social housing, but remain ineligible for the subsidy. Wellington City Council, for example, provides an estimated 6.4% (1900) of all rental dwellings (29,364) in the Wellington City area (in 2010, prior to the introduction of social housing reforms, this figure was around 8.3%). Most of the Wellington City Council stock is bedsits and one-bedroom units, whereas Kāinga Ora provides mostly two and three bedroom units. Given the time required to reconfigure Kāinga Ora stock, extending the income-related rent subsidy to council housing would make a significant difference to older people on low-incomes.

As evidenced by the successful Community Finance investment vehicle, there is a need for low-interest finance for social housing (in addition to the income-related rent subsidy), and we anticipate the long-term 2% finance proposed by New Zealand first will be welcomed by local councils providing social housing.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

According to research by Philippa Howden-Chapman and others, three quarters of older Pākehā (65+) lived in mortgage-free housing and 87% in owner-occupied housing in 1996, while at the same time only half of older Māori lived in mortgage-free housing and 70% lived in accommodation which they owned. By 2013, the rate for Pākehā living in owner-occupied housing had dropped to around 84%, and to around 60% for Māori.

Research by Fiona Cram and others found that older Māori 65+ have a higher home ownership rate than the overall Māori population, largely as a result of access to Māori Affairs home loans. Māori aged 50—64 years are less likely to own their own homes, and more likely to experience housing stress as they enter retirement.

Detailed data on current council housing tenants is not publicly available, but again using the Wellington example, in 2010 13.8% of tenants were Māori. Despite a lack of data, given the critical role in the delivery of pensioner housing previously fulfilled by councils, and the fact that older Māori are less likely to live in owner-occupied housing, it seems likely that older Māori would access and occupy this type of housing were it to be properly funded and supported by central government.

Will it make a difference for Māori? Yes – given the low home ownership rates amongst older Māori, central government support for council housing will make a difference for Māori. One further consideration may be the cultural responsiveness of housing for older Māori (a recent partnership between Hutt Valley Council and Te Rūnanganui o Te Ātiawa provides a potential model).

2. Investigate the option of families to capitalise on the Universal Family Benefit as a deposit on their first family home

The Social Security Act 1938 introduced a means-tested Family Benefit. The Universal Family Benefit was introduced in 1946. This was paid for each dependent child under the age of 16. In 1958, the Family Benefit rules were changes to allow families to capitalise on future payments into a lump sum amount to use as a deposit on a house. It was formerly introduced through the Family Benefit (Home Ownership) Act 1958. In 1990, the Universal Family Benefit was repealed, largely superseded by the targeted Family Support benefit (Deborah Keating’s 2002 thesis explores the policy in detail).

Will it work?

Many New Zealand families were assisted into home ownership through the scheme between 1958 and 1986.

But would it work now?

Today’s targeted Working for Families tax credits change depending on a family’s (likely fluctuating) income over time. We can attempt to calculate a universal family benefit based on Working for Families Tax Credits for a family with a median household income.

We have modelled a scenario using the Estimate Your Working for Families Tax Credit Calculator offered by Inland Revenue. We have made the following assumptions:

3 year old child (D.O.B.: 1 October 2017)

1 year old child (D.O.B.: 1 October 2019)

Two adults

$85,041 household income

Using the IRD calculator, the Working for Families Tax Credit – $101 per week for two children, $32 per week for one child, for a total of $5,252 per year for 13 years ($68,276) and $1,664 per year for 2 years ($3,328) for a total of $71,604 over 15 years.

For a 3-bedroom KiwiBuild home with a sale price of $650,000, the benefit capitalisation would amount to 11% of the purchase price. KiwiBuild offers mortgages with a 10% deposit, which would mean a family on median income would be able to utilise benefit capitalisation to fund the full deposit. For less over-heated housing markets outside of Auckland, benefit capitalisation could amount to closer to 20% of the purchase price.

At the time benefit capitalisation was introduced in 1958 it was capped at £1000 per family in 1964, or the equivalent of $50,214 in 2020 if adjusted for inflation (calculated using the Reserve Bank inflation calculator) – which would be sufficient to for a 10% deposit on a KiwiBuild home in most areas outside of Auckland. Removal of benefit capitalisation caps, or else the introduction of regionally-based caps would be a policy consideration.

Overall, this policy would make a huge difference to families with children, enabling them to secure owned housing without the large deposit required. Affordability of mortgage payments may still be an issue (even with a full deposit covered by benefit capitalisation), particularly for families on lower incomes, who would benefit from access to progressive home ownership options.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

An article in Te Ao Hou, No. 29 December 1959 detailed how family benefit capitalisation could be used to finance Māori housing, including specific provisions for housing on whenua Māori. Anecdotally, many Māori whānau were assisted to secure home ownership thanks to the scheme. With Māori home ownership rates (28% in 2013) lower than for the general population (57% in 2013) with a downward trend over time, this policy would make a significant difference for whānau Māori.

3. Promote and implement innovative housing solutions on Māori title land using relocatable dwellings and appropriate changes to the Building Act

The current government has introduced a series of changes to the Building Act, which came into effect in August 2020. Exemptions include single-storey detached buildings (without bathrooms or kitchens) up to 30m2. The changes are intended to enable home owners to make small changes to their homes and build sleepouts and sheds without the need for consents.

Relocatable dwellings are already offered by Te Puni Kōkiri as part of a suite of housing solutions offered to whānau on whenua Māori, often currently living in substandard owned dwellings.

This policy appears to build on both of these initiatives.

Will it work?

Current exemptions (Schedule 1 of the Building Act) do not extend to self-contained units, and exempt sleepouts need to be supplementary to / associated with a primary dwelling). If a central utility building or buildings (including kitchens and/or ablutions – such as a marae) were to be consented, theoretically a series of associated sleepouts could be erected without consents, although any resource consent requirements would still apply.

The relocatable component of the policy has potential – initiatives such as the Māori Modular House (a partnership between TOA Architects and Mike Greer homes) utilise multi-proof consents to reduce compliance and prefabrication to increase quality and minimise overall construction costs, and are suitable for erection of whenua Māori. Although the scheme is still in the pilot phase, this solution (and others like it) have immense potential to improve quality and reduce the cost of housing on whenua Māori.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

The Building Act exemptions won’t make a huge difference for Māori in rural areas, although in urban areas the ability to erect larger sleepouts without consents would be of benefit to whānau living in overcrowded conditions.

Māori are overrepresented amongst those experiencing extreme housing deprivation, including in rural areas. The ‘Māori housing need, stock and regional population change’ in Te Tai Tokerau sub-report of the ‘Māori Housing Supply and Demand in Te Tai Tokerau’ series of reports commissioned by Te Puni Kōkiri, the Ministry of Social Development and Housing New Zealand (now Kāinga Ora) and published in 2019 indicates (noting serious data gaps and limitations) that an estimated 6,047 dwellings occupied by Māori are in poor and serious condition, 2,604 are in serious condition, and 3,444 are in poor condition.

This component of the policy relating to relocatable dwellings would benefit both whānau currently living in substandard owned homes on whenua Māori, as well as whānau seeking to build new housing and return to their whenua. Although difficult to quantify, research in 2013 found that approximately 80% of Māori freehold land was ‘under-utilised’ (40%) or ‘under-performing’ (40%). Although this research was geared towards the primary sector, it is also indicative of the current limitations on developing whenua Māori for housing.

Will this make a difference? Likely, yes – although this policy needs to be complemented by a range of policies aimed to address the barriers to utilising whenua Māori for housing, including the reform of the Kāinga Whenua loan scheme and alternative finance options, as well as the continuation of the Māori Housing Fund (including capacity and capability building support) delivered by Te Puni Kōkiri, improved district plan provisions for papakāinga, and possible further amendments to Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993.