Finally – the National Party. After three years in opposition, National is vying for the opportunity to make a comeback. What will National do to improve housing outcomes, and how will these policies impact Māori? Te Matapihi provides a perspective.

National have outlined a comprehensive plan to address housing unaffordability, which they have described as “the most pressing social issue facing New Zealand”. If elected, National will:

- Amend the RMA to require councils to permit more housing in the first 100 days in government

- Repeal the RMA and develop a new Planning and Development Act within their first term

- Enable Community Housing Providers to build more social houses through setting aside $1billion of capital funding from the existing Kāinga Ora borrowing facility for community housing providers to access

- Progress a rent-to-own or shared equity scheme

- Address the State Housing wait list

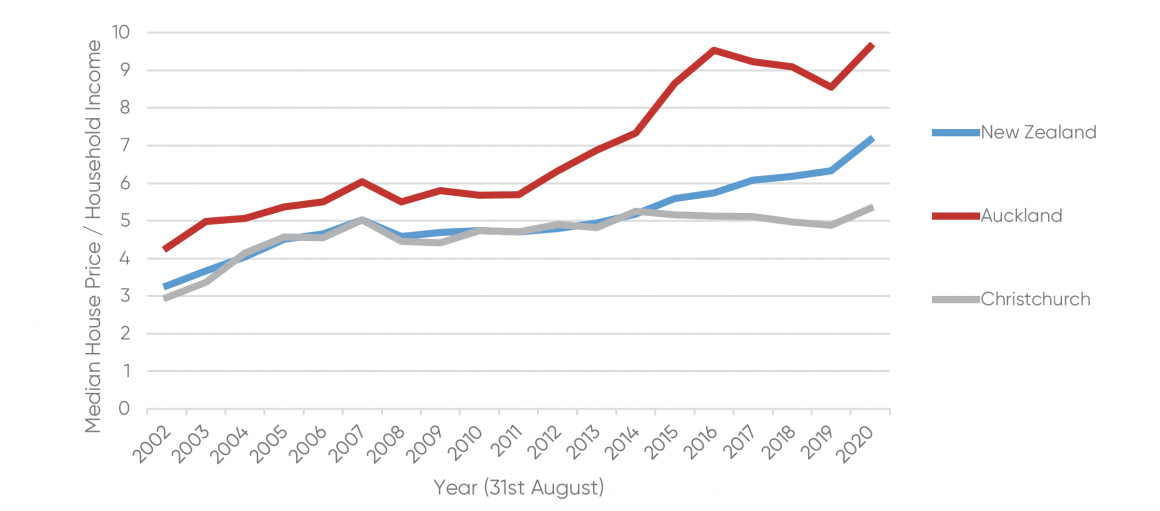

Table 1. National’s Housing Policies – Summary

We will be unpacking the following policies in detail:

- Introduce emergency legislation to address housing affordability, and repeal the RMA within the first term

- Move the bright line test from five years back to two years, and repeal the ring fencing of rental losses

- Reinstate public housing tenancy reviews, and implement a three-strikes system for anti-social behaviour in social housing

1. Emergency legislation and repeal of the Resource Management Act

Similarly to Labour (and most minor political parties this election), National have pledged to repeal and replace the Resource Management Act if elected. So how does National’s policy differ from Labour’s?

The key difference is the proposed introduction of emergency legislation, similar to the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act 2011 within the first 100 days in government. The Christchurch Earthquake recovery is used as an example of changes to the Resource Management Act (in this instance, temporary) being used to change planning rules which may result in increased housing affordability.

The proposed legislation will:

- Require Councils to immediately open up 30 years’ worth of growth for urban development in Tier 1 and Tier 2 urban areas

- Suspend the appeal process so district plans can be completed right away

- Suspend requirements for infrastructure to be built prior to zoning

- Streamline the consenting process, including allowing any district council to consent any application

This would be followed by the repeal of the Resource Management Act within National’s first term. Under this policy, the Resource Management Act would be replaced with an Environmental Standards Act and a Planning and Development Act.

Will it work?

The proposal to repeal and replace the Resource Management Act with two-part legislation is similar to Labour’s policy, which is based on the comprehensive review of New Zealand’s resource management system. As this is covered in our analysis of Labour’s housing policy, we won’t look at this in detail here.

Instead, we will focus on the proposal to introduce emergency legislation, similar to legislation passed in the wake of the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquakes.

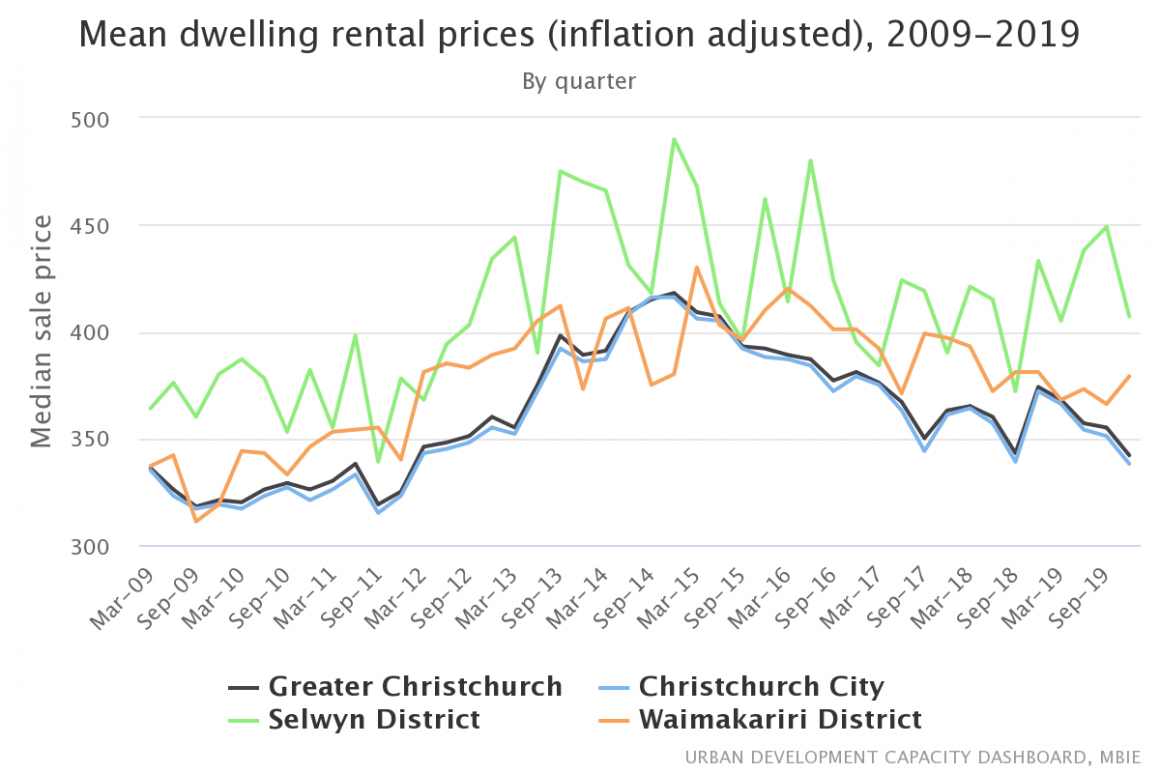

Immediately post-earthquake, housing affordability was a major issue for both renters and home-owners due to the significant undersupply created by the earthquakes. Data has shown that the post-earthquake rebuild has resulted in increased housing supply, and reduction of house prices and rents across Christchurch, and that house prices relative to incomes are lower in Christchurch when compared with Auckland and New Zealand overall.

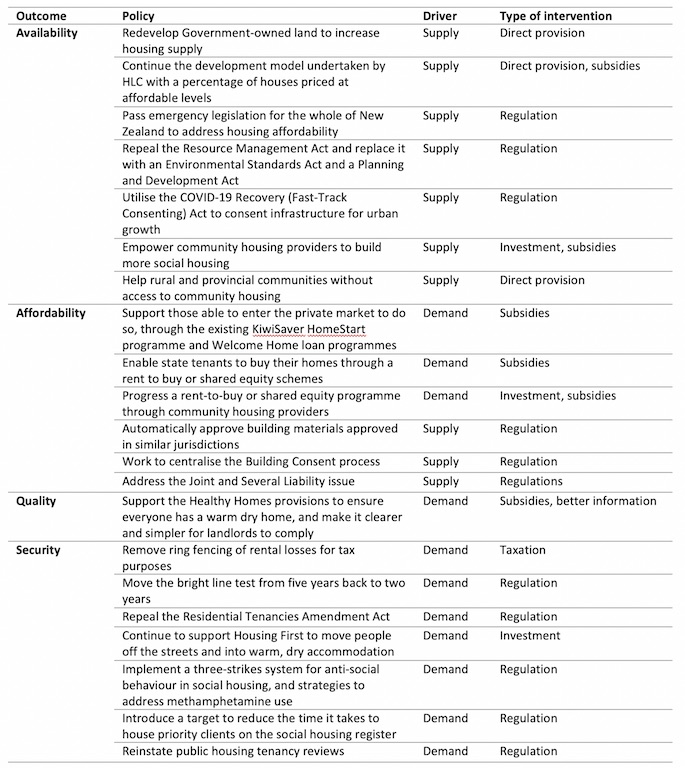

Chart 1. Median dwelling sale prices (inflation adjusted), 2009 – 2019

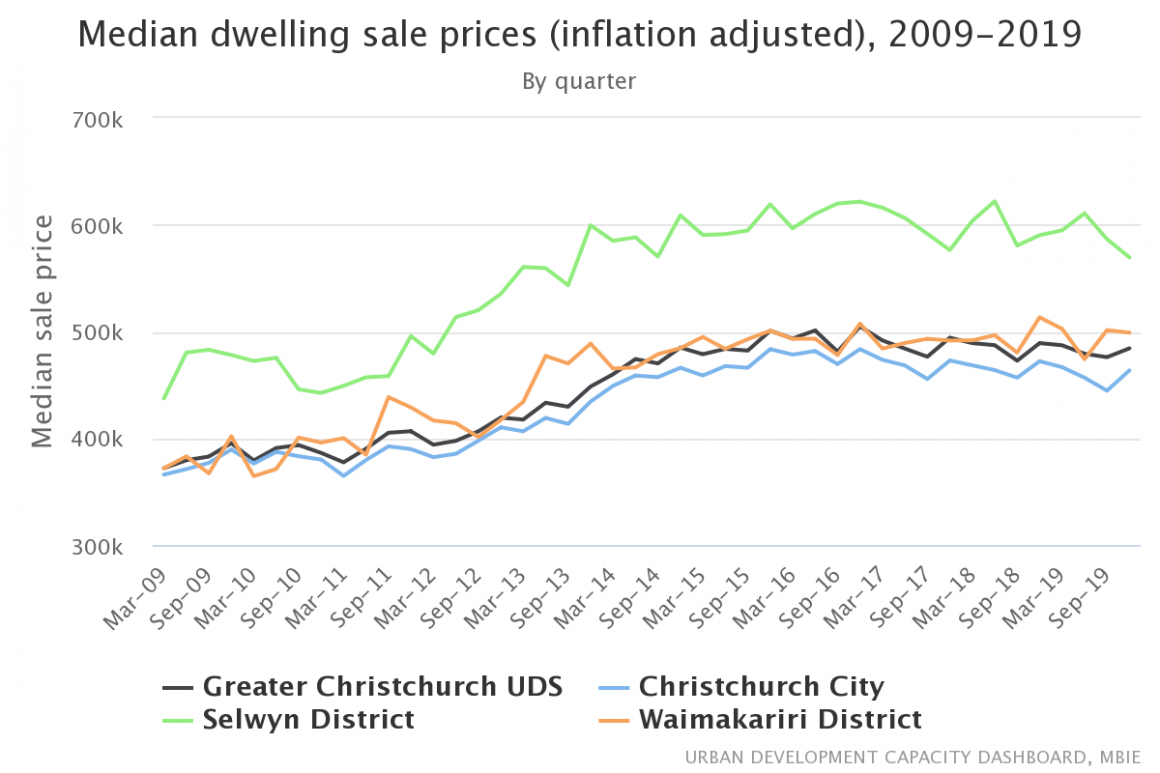

Chart 2. Mean dwelling rental prices (inflation adjusted), 2009 – 2019

Chart 3. House prices compared to incomes in New Zealand

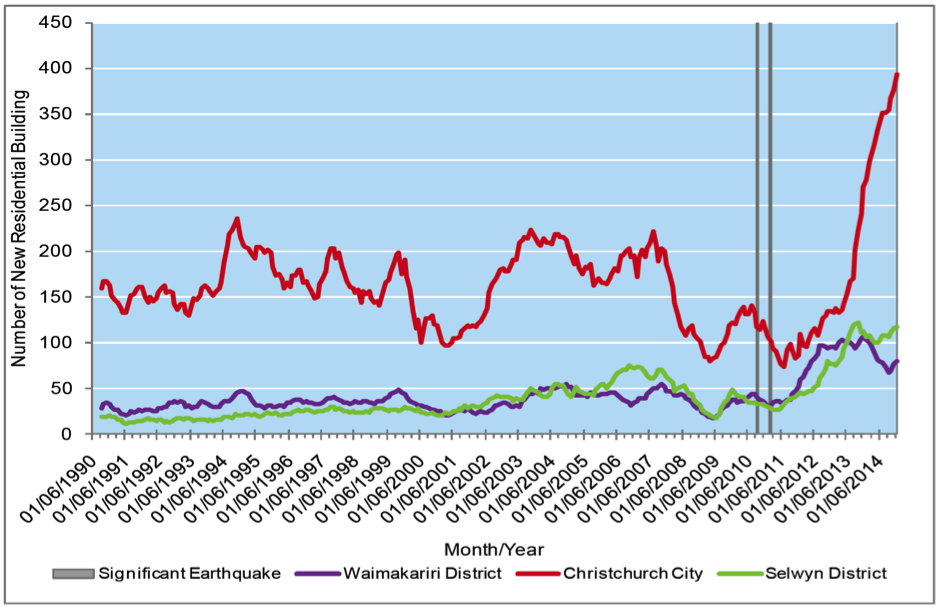

The Land Use Recovery Plan 2013 is a statutory document prepared under the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act 2011. A report monitoring progress against the 50 actions in the Land Use Recovery Plan was completed in March 2015. The report indicated that 28,500 sections were rezoned from rural to residential between 2012 and 2014, nearly three-quarters of all potential sections that could be provided for in greater Christchurch. The report also found a significant increase in new housing between 2011 and 2014, with lower residential intensification rates than targeted due to the large number of houses built in greenfield areas.

Chart 4. New housing in greater Christchurch six month running average, 1990 – 2014.

Commentators have also suggested that investment into infrastructure and access to development finance for developers – in addition to planning provisions – were key factors in the success of the Christchurch rebuild.

The policy also specifically references the Special Housing Areas legislation, which was introduced by the National-led government in 2013. The Act was not extended by the Labour-led government and expired in September 2019. Research conducted in 2018 found that Special Housing Areas did not result in more affordable housing, and instead generated an average price increase of 5%.

Will this policy work? Likely, yes, but given the findings of research into Special Housing Areas, more work is required to understand the impact on highly supply-constrained markets such as Auckland. Investment into infrastructure, and availability of low-interest finance for development will also be key to the success of this policy.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

Research conducted in 2013 showed that Māori suffered some of the worst effects on wellbeing during the 2010-12 earthquakes; further research in 2014 described the variety of Māori responses to the earthquakes.

The Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Act 2011 and later, theGreater Christchurch Regeneration Act 2016include specific statutory provisions for Ngāi Tahu as a partner in the rebuild, which was seen as a positive development. Māori who cannot claim mana whenua status were not specifically provided for in planning process, other than through community representation, however documents published by Ngāi Tahu show the involvement of mataawaka alongside Ngāi Tahu.

Outcomes include the establishment of Matapopore Trust and the integration of Ngāi Tūāhuriri histories, narratives, values and aspirations in the rebuild of the city; the establishment of a Ngāi Tahu home ownership programme; Ngāi Tahu-led housing developments (such as Ngā Hau e Whā Housing development in Aranui); and plans for the future development of Kaiapoi Māori Reserve 873 (including for housing).

Will it make a difference for Māori? If specific provisions for mana whenua partnership are included in the legislation, than yes, this policy could make a difference for Māori.

2. Bright line test reform and repeal ring-fencing of rental losses

The Bright-line test is designed to disincentivise buying and selling property for profit. Historically, the intention test (a somewhat subjective measure of whether or not you purchased property with the intent to sell it at a profit) applied.

New Zealand does not have a capital gains tax, but we do have income tax. The bright line test enables IRD to classify the net profit of sales from property sold within five years of purchase to be taxed as income.

The following exemptions apply:

- If the property is your main home

- You inherited the property

- You’re the executor or administrator of a deceased estate

The current bright line test was introduced in 2015 through the Taxation (Bright-line Test for Residential Land) Act 2015, which made amendments to the Income Tax Act 2007 and the Tax Administration Act 1994. The two year rule – which was introduced with the initial legislation – applies to properties purchased on or after 1 October 2015 through to 28 March 2018.

The rule was updated in 2018 through a Supplementary Order Paper to the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2017-18, Employment and Investment Income, and Remedial Matters) Act 2018. The new five year rule applies to all properties purchase after 28 March 2018.

National are proposing to repeal the 2018 amendments, moving the bright line test from five years back to two years.

The National party policy also states that they will remove the ability of landlords to ring fence losses.

The ring-fencing rule was introduced through the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2019–20, GST Offshore Supplier Registration, and Remedial Matters) Act 2019, an amendment to the Income Tax Act 2007. Basically, ring-fencing means that from the 2019-20 income year onwards, landlords can only claim deductions up to the amount of income they earn from rental properties for that year, and cannot use rental losses to offset other income like salary and wages.

The following exemptions apply:

- your main home (if you have more than one home, this is the home you have the greatest connection with)

- property that comes under the mixed-use asset rules

- farmland

- property used mainly as business premises

- property you’ve identified to us as land that will be taxed on sale, regardless of when it’s sold

- property owned by companies (other than close companies)

- employee accommodation

- property owned by Government enterprises

At the time the bill was being considered, the Independent Specialist Tax Advisor to the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee noted – as advised by officials and submitters – that the impact of the policy was uncertain, and that the introduction of ring-fencing has the “potential to impact on rents charged and reduce supply of residential properties”, both of which would “impact negatively on an already tight market”.

Will it work?

The policy implies that moving the bright line test from five to two years will improve the rental market. The policy states that the repeal of “unwieldy rental regulations” will “stop good landlords from fleeing the market due to cost, bringing down the cost of rents and enduring there are enough rental properties to meet demand.”

There is no evidence to suggest that the policy would have the intended effect of improving the rental market. It is instead likely that shifting back to the two-year rule will instead encourage landlords to sell property more frequently, which often results in tenants being forced to move or experiencing rent increases.

The bright-line test is the closest thing New Zealand has to a capital gains tax. If the intention is to enable property speculators to buy and sell property for profit quicker and without being taxed, then yes, this policy will work.

There is no research available (as yet) into the impact of the ring-fencing on rental prices, however Westpac’s 2018 report ‘Tax and house prices’ predicted that rents would likely increase (not quantified), house prices would decrease (by up to 6%), and home ownership rates would increase. (not quantified).

Will it make a difference for Māori?

With Māori homeownership rates much lower than non-Māori, and Māori more likely to be renters (and much less likely to be landlords), it’s unlikely that the proposed changes to the bright-line test will make a (positive) difference for Māori. The impact is yet to be quantified, but assuming a small rental increase due to the introduction of the ringfencing rules, changes to these rules may make a small difference to the 53.3% of Māori who rent.

3. Reinstate reviewable tenancies for public housing and implement a three-strikes system for anti-social behaviour in social housing

In 2013, the National-led government introduced reviewable tenancies through the introduction of Social Housing Reform (Housing Restructuring and Tenancy Matters Amendment) Act 2013. The ethos behind this policy was that social housing should be available for those in highest need, for the duration of that need. This superseded the earlier ‘state home for life’ policy introduced from around the 1950s.

The Ministry of Social Development introduced tenancy reviews from 1 July 2014. Tenancy reviews were initially targeted at state housing tenants paying market or near-market rents, but the policy applied to all new and existing state housing tenants, and tenants of Community Housing Providers receiving the income-related rent subsidy. The reviewable tenancies process was designed to assess existing tenancies against criteria relating to affordability, accessibility and sustainability, and to shift households deemed ineligible for social housing into private housing, with reviews to occur at least every 3 years.

At that time, the following tenants were exempt from periodic tenancy reviews:

- People 75 and older

- People whose house is modified for their needs such as wheelchair access

- Households working with a Children’s Team in the Ministry for Children Oranga Tamariki,

- Those with an agreed lifetime tenure with Housing New Zealand.

In March 2018, the Labour-led government paused periodic tenancy reviews of public housing tenants, whilst further exemption criteria were considered. New exemption criteria were introduced in September 2018. These include:

- Families with dependent children 18 years and older

- Households where the tenant or their partner is aged 65 or older

- Households where the tenant or their partner has a permanent or severe disability or a health condition

- Tenants that are providing full-time care at home for a person other than their spouse or partner who would otherwise need hospital-level or residential care

- Those with agreed lifetime tenure with Housing New Zealand (now Kāinga Ora)

At the time the change was implemented, the exemptions resulted in 81% of all public housing tenants being exempt from review, an increase from 14% under the previous policy.

The National policy proposes to reinstate public housing tenancy reviews, as per the 2014 policy.

The ‘three-strikes’ policy is popular in Australia to manage minor and moderate antisocial behaviour amongst public housing tenants. Under this system, the social landlord can issue tenants with three strikes – or warnings – for behaviour that breaches their tenancy agreement. A third strike means the tenancy will end and the tenant will have to leave public housing. Definitions of antisocial behaviour and policies for enforcement vary by state.

Will it work?

In the 2010 report Home and Housed: A Vision for Social Housing New Zealand, the Housing Shareholders Advisory Group recommended that “no existing tenant should have his or her lease simply terminated”, and advised HNZC (now Kāinga Ora) to “offer, not push”. The Productivity Commission’s 2012 report on Housing Affordability cautioned against the introduction of reviewable tenancies, stating that “excessive reliance on the private rental market to accommodate former HNZC tenants may undermine the improvements in wellbeing that has been achieved for these tenants through state housing.”

There is no evidence that reviewable tenancies create better outcomes for tenants. With housing in the private rental market becoming increasingly unaffordable and supply-constrained in markets such as Auckland (along with housing quality and health issues), this policy poses a real risk to social housing tenants, many of whom will have complex needs. Additionally, the impact of return-migration is yet to be quantified, with early reports indicating a spike in private rental market demand.

Research from Australia has identified systemic issues with the three-strikes policy, which has had a disproportionate impact on tenants with complex needs. Women affected by domestic violence, children, Indigenous people, and people (or family members of) who have alcohol and drug addictions area all vulnerable to discrimination under the three-strikes policy. Further research has concluded that laws and policies regarding tenancy termination are in conflict with the objective of sustaining tenancies for vulnerable people, and that appropriate social support should be provided without the threat of tenancy termination.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

With Māori making up 37% of all Kāinga Ora tenants, removing the 2018 exemptions for reviewable tenancies will disproportionately affect Māori. The undersupply of affordable rental housing in the market as well as the disproportionately low incomes of Māori households are additional factors that will see this policy negatively impact whānau Māori. Additionally, Māori have lower life expectancy than non-Māori (in 2013 this was 77.1 years for Māori women, 73 years for Māori men vs 80.3 years for non-Māori men and 83.9 years for non-Māori women, although the gap has reduced over time), and will be disproportionately affected by the proposed changes in review exemptions from 65 to 75 years.

Research from Australia has shown that the effect of the three strikes policy is indirect racial discrimination, and that Indigenous people are disproportionately affected. Although a neat equivalency between Indigenous people in Australia and Māori cannot be drawn, it seems likely that the introduction of the three-strikes policy would disproportionately affect Māori.

This is the fifth article in Te Matapihi’s Māori housing election year series. The series concludes with a ‘scorecard’ comparison of what works, what doesn’t, and what’s likely to make a difference for Māori.