As the incumbent, Labour have a clear advantage when it comes to policy, building on a previous term in government. With some major structural changes so far, as well as some well-publicised perceived failures, will Labour be able to prove to voters that they deserve another term to see these reforms through?

Last election, Labour made a clean sweep of the Māori electorates and made a clear commitment to Māori constituents. With a high number of credible Māori MPs at the helm, it would be expected that Māori interests would be at the forefront of policy development.

This election, Labour have both a general housing policy and a Māori manifesto.

The housing policy sets out a five point plan to boost housing supply during the economic uncertainty of COVID-19 –

- Support construction through the Residential Development Response Fund, which can be accessed by builders and developers

- Deliver 18,000 additional public and transitional houses by 2024

- Support first home buyers with First Home Grants and Loans, progressive home ownership and KiwiBuild

- Work with the construction industry to improve productivity through the Construction Sector Accord

- Remove planning barriers to residential construction, including by replacing the RMA

As well as build on existing government policy to –

- Fund 8000 new public and transitional homes

- Building Act reform, reducing the need for consents for low-risk building work

- Funding improvements to around 9,000 additional low-income households through the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme

- Continue to roll out a Progressive Home Ownership scheme

- Implement the Homelessness Action Plan to prevent people becoming homeless and reduce reliance on motels for emergency accommodation

- Continue to partner with iwi and Māori housing providers to get more whānau into healthy and secure homes

Labour has also pledged, if re-elected, to regulate property managers.

They will also:

- Expand the Healthy Homes Initiative for housing basics like heaters, curtains, bedding and floor covering

- Strengthen healthy home compliance and enforcement efforts by Tenancy Services

- Introduce a national register to actively track and treat rheumatic patients

Labour’s Māori manifesto also has the following housing-specific policy point –

- Strengthen Māori housing outcomes through collaborative partnerships, home-ownership models, and papakāinga provision

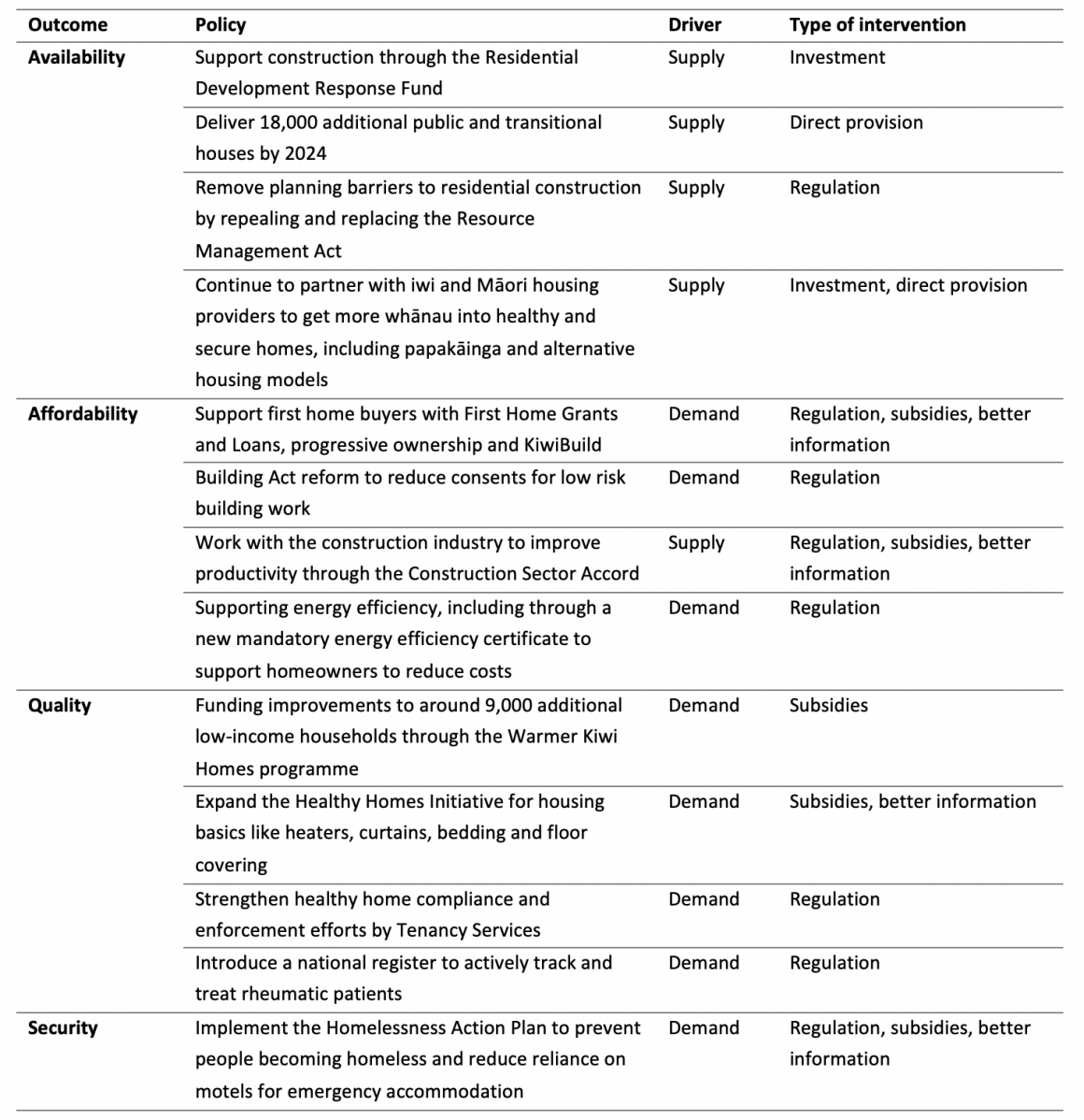

Table 1. Labour’s Housing Policies – Summary

The Labour housing policy largely builds on existing government policy – if you remove the already-implemented policies, Labour’s housing policy is fairly slim on new policy (and details). In stark contrast to the previous election, KiwiBuild and the accompanying ambitious build targets have been omitted.

We’ve selected three policies for more in-depth analysis. These are:

- Deliver 18,000 additional public and transitional houses by 2024

- Repeal and replace the Resource Management Act

- Work with the construction industry to improve productivity through the Construction Sector Accord

The first point focusses on government-led supply-side solutions – notable in relation (and in contrast) to Labour’s election 2017 flagship housing policy. The second and third points focus on regulatory changes to support supply of land for housing, and improving construction sector productivity.

Although not selected for more in-depth analysis, the housing quality and health-oriented policy interventions will continue to make a significant difference for whānau Māori living in inadequate housing.

1. Deliver 18,000 additional public and transitional houses by 2024

During the 2017 general election, Labour pledged to build 100,000 homes over ten years. In September 2019, the government initiated the KiwiBuild reset, dropping the target and realigning the fund. Recent reports indicate that the government has stopped publishing estimates of the total housing shortage in New Zealand. The lack of data makes it difficult to measure progress, or accurately estimate demand.

This election, Labour have eschewed targets in favour of broad policy statements. One of the few targets in the 2020 policy is to deliver 18,000 additional public and transitional houses by 2024, which is a far cry from the ambitious targets set during the previous election.

Will it work?

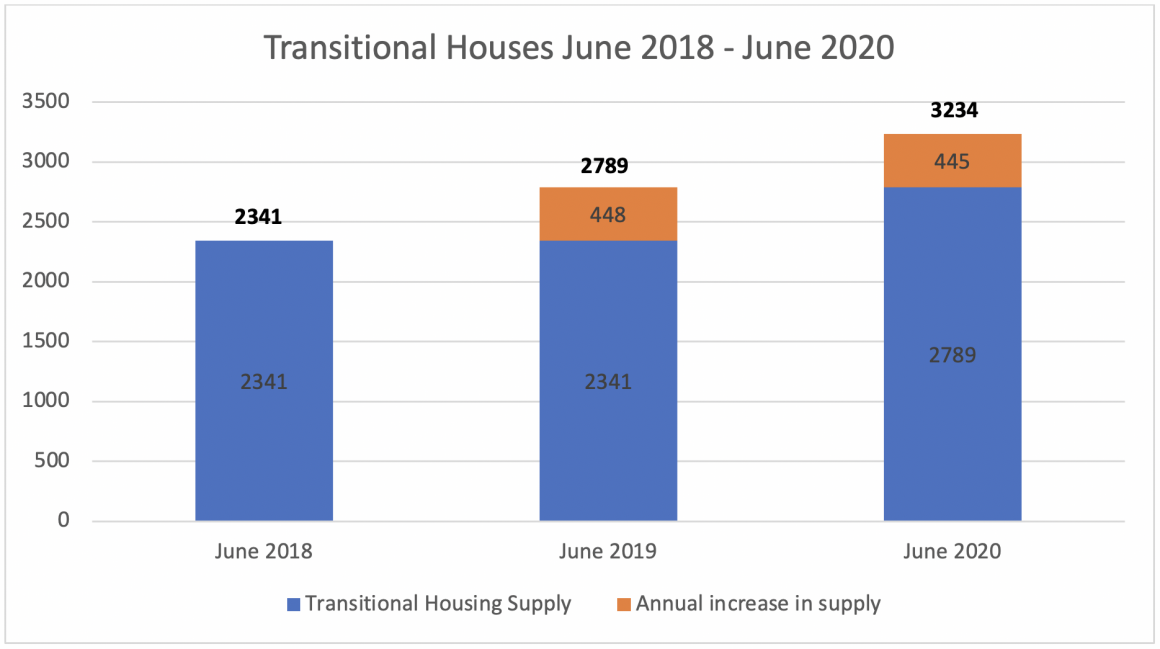

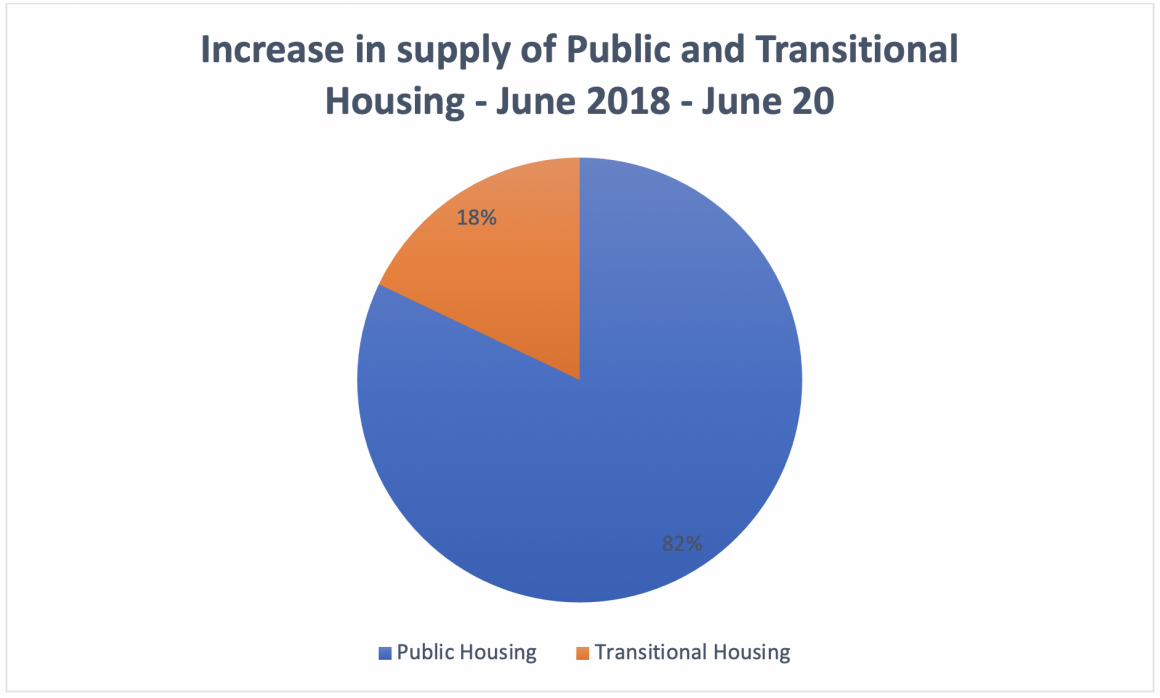

As detailed in our analysis of the Greens housing policy, the current housing waiting list is over 18,000 and growing annually at a rate of 40.7% on average. There is also a high demand for transitional housing. Labour doesn’t provide a breakdown for the 18,000 additional public and transitional houses – by providing a combined total, this policy is a bit tricky to unpack. We have made some assumptions based on current government data.

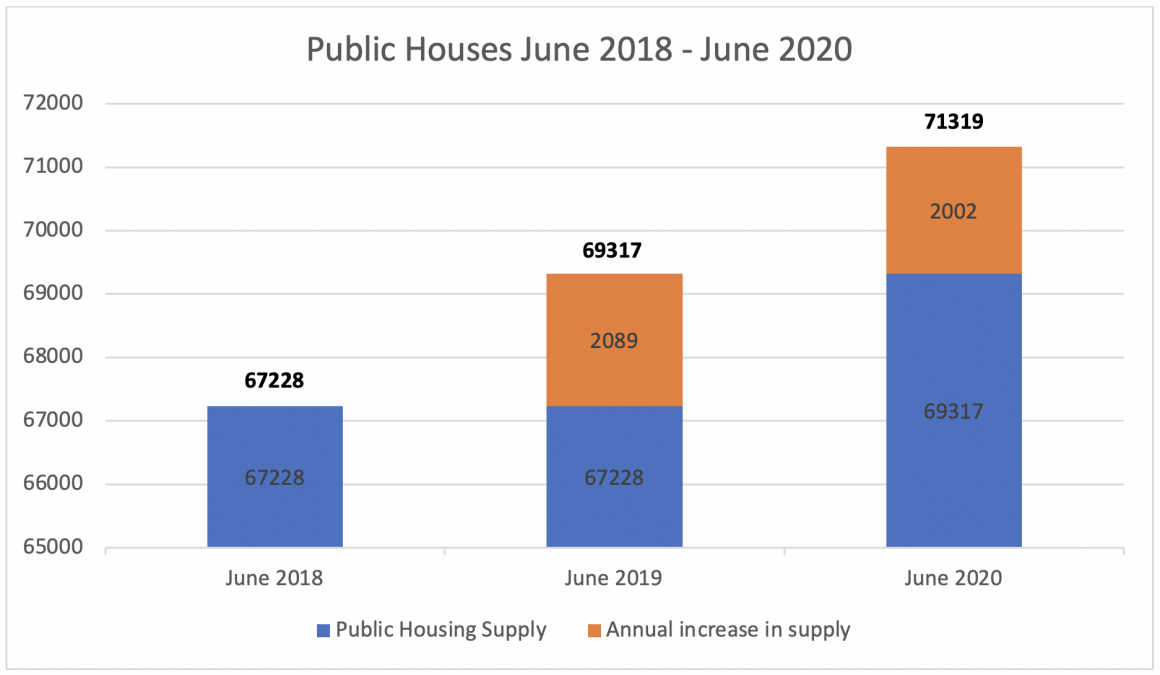

According to the Housing Quarterly report for June 2020, the overall supply of public houses (delivered by both Kāinga Ora and Community Housing Providers) has increased by 4009 between June 2018 and June 2020.

Chart 1. Public Houses June 2018 – June 2020

Chart 2. Transitional Houses June 2018 – June 2020

During the same period, the government offered an additional 893 transitional housing places.

Chart 3. Increase in supply of Public and Transitional Housing – June 2018 – June 2020

Note: based on average increase in supply from June 2018 – June 2020.

We have assumed 18% transitional housing and 82% public housing (made up of homes delivered by both Kāinga Ora and Community Housing Providers). We have assumed a four-year timeframe (June 2020 to June 2024). On this basis, the policy will deliver 3690 public houses per year over four years, and an additional 810 transitional housing places per year over four years. This represents an increase of approximately 180% for both public and transitional housing.

Overall, an unambitious target that will make a small difference, but will not deliver public and transitional houses to the level required to meet current demand.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

With Māori overrepresented amongst those on the housing register (approximately 50%), as well as those applying for transitional housing (26% of those living without shelter, 18% of those in temporary accommodation, and 36% of those sharing accommodation as reported by the 2018 Severe Housing Deprivation Estimate), this policy will make some difference, but not to the degree required.

2. Work with the construction industry to improve productivity through the Construction Sector Accord

Much of the COVID-19 economic response has centred on the construction industry. This has been problematic from a gender equity perspective (with women making up the majority of the 11,000 people made redundant due to COVID-19). Which raises the question – is this a housing policy or an economic policy? Answer – it’s both, but for our analysis we’ll be specifically looking at the housing aspects.

The Construction Sector Accord was established in April 2019. The Accord includes Accord Ministers (Ministers for Building and Construction, Housing and Urban Development, Economic Development, Workplace Relations and Safety, Infrastructure, Education, State Services, and Health), government agencies (Kāinga Ora, Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, NZ Transport Agency Waka Kotahi, Treasury, Worksafe, and the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment), as well as the Accord Development Group made up of sector leaders (Fletcher Construction, Fletcher Residential, MBIE, Construction Health and Safety NZ, Naylor Love, E Tū, Downer NZ, Tonkin + Taylor, Project Unite, MinterEllison, Watercare, Registered Master Builders, Fonterra, and Construction Strategy Group).

The Accord is a high-level strategic document that has been co-developed by government and industry and includes a number of shared goals and principles for working together and set out priority areas for a shared work programme. The work programme has an explicit priority work area related to housing – “more houses and better durability: boost the supply of housing and ensure all new houses are built to perform well over their lifetime”.

Will it work?

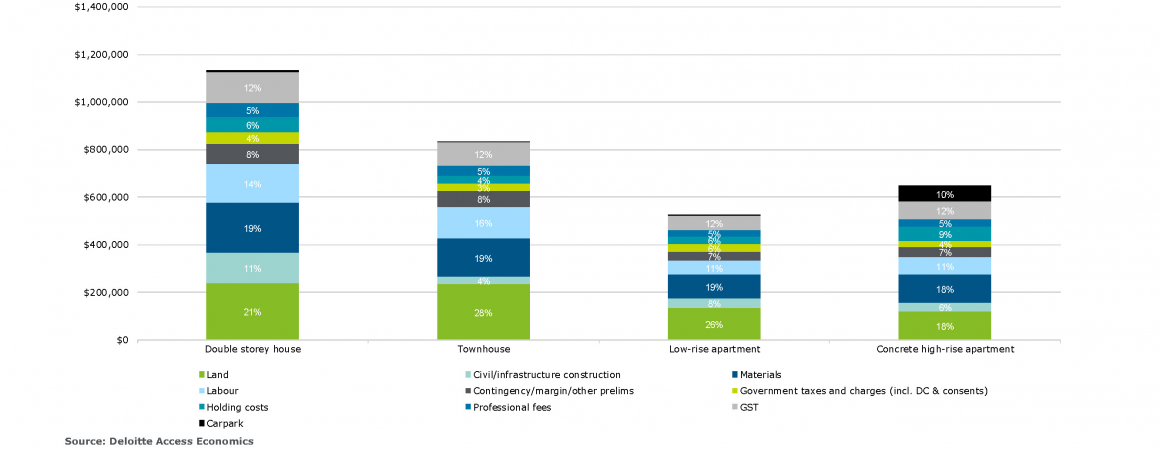

Research commissioned by Fletcher Building and published by Deloitte in late 2018 examined the cost of residential housing development, with a focus on building materials. The report found that land and associated infrastructure are by far the largest cost components of residential housing development, with building materials being the second largest component. Labour was the third biggest contributor, with GST, government fees and charges (including development contributions and consents), holding costs and professional fees making up the remainder.

Chart 4. An illustrative example of the cost contributors to residential housing development in Auckland. Source: Deloitte Access Economics.

The report also examined cost differences between Australia and New Zealand, and found that when comparing like with like the cost of labour and materials was cheaper overall, but other factors, such as builder’s margins, GST, engineering design in response to seismic risk, higher transportation supply costs, and a smaller market all contributed to cost differences between Australia and New Zealand.

Will increasing construction sector productivity see a reduction in housing prices? To a degree, but unless the rapidly escalating cost of land can be reined in, construction industry productivity is unlikely to make much of a difference to house prices. Will the construction sector accord lead to regulatory and changes to industry practices that will see housing quality increase? Yes, this is a likely longer-term outcome of the accord.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

Although housing affordability is unlikely to be substantively impacted by the activities of the accord, the health aspects of the policy – like the various housing quality and health policies promoted by Labour this election – have the potential to make a difference for whānau Māori currently living in substandard housing over the longer-term.

3. Repeal and replace the Resource Management Act

Land-use regulation is a hot topic this election, with both major parties promising to repeal and replace the Resource Management Act if elected.

The use of land for housing has been a persistent area of inquiry for both National and Labour-led governments, with numerous reports indicating that land use regulation is a cost contributor to high house prices. The Productivity Commission’s 2016 report on Using Land for Housing found that insufficient supply of land is a major contributor to house price growth, particularly in Auckland, and recommended a deeper review of the planning system (amongst other recommendations).

In late 2018, the government initiated a comprehensive review of New Zealand’s resource management system. The final report, New Directions for Resource Management in New Zealand, was published in July 2020. The report recommends the RMA should be repealed and replaced with a new legislation called the Natural and Built Environments Act, which will focus on environmental protection, and the introduction of a new Strategic Planning Act, which would inform the development of regional spatial strategies.

If elected, the Labour government will implement the recommendations of the inquiry.

Will it work?

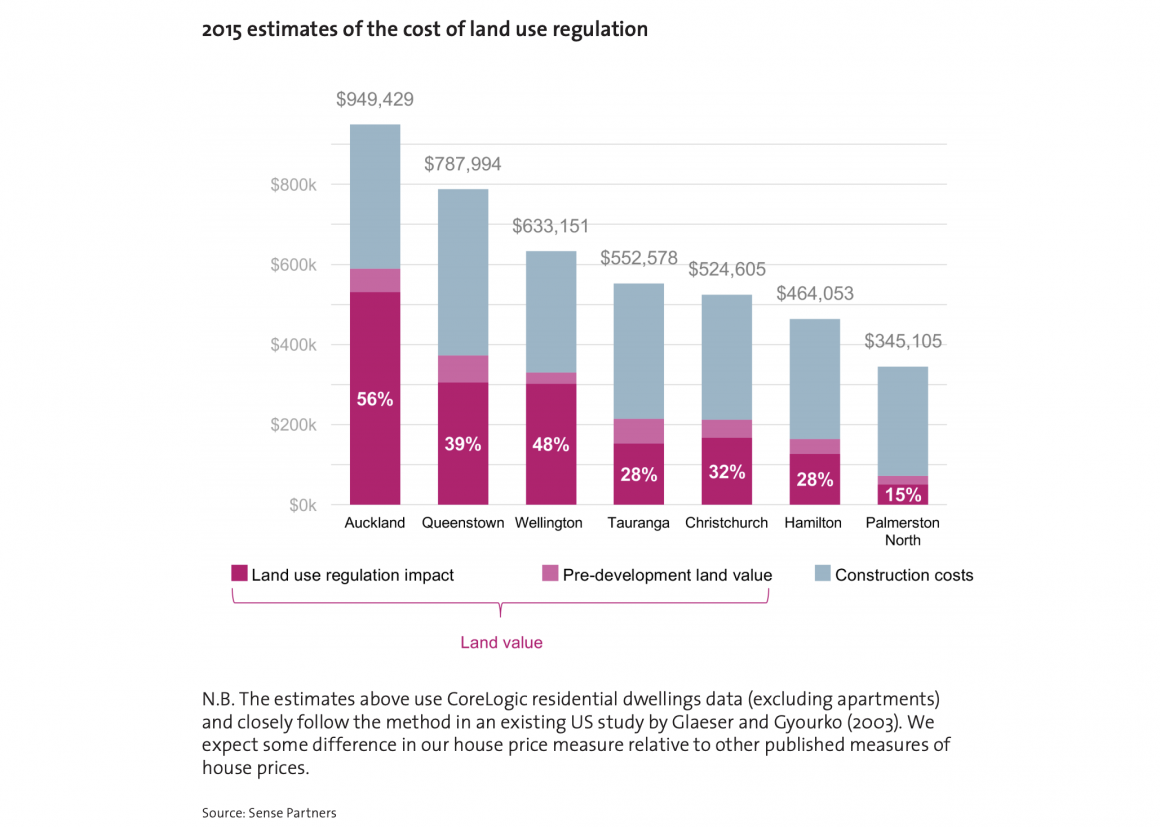

Research by Sense Partners, detailed in their July 2017 report Quantifying the impact of land use regulation: Evidence from New Zealand, found that land-use regulation has pushed up property prices across New Zealand’s cities, with 2015 estimates showing that land use regulation could cost up to 56% of an Auckland home.

Chart 5. Land use regulation could cost 56 percent of an Auckland home. Source: Sense Partners.

The report found that although the extent to which land use and building regulation contributes to the cost of housing is difficult to measure, Sense Partners’ analysis suggests that there are potentially large impacts which make housing supply relatively unresponsive to increases in demand i.e. land use regulation is playing a large role in driving up prices. Significantly, the report found only a mixed and modest relationship between density and prices i.e. increased density is not the silver bullet to decrease the cost of land.

Economist Shamubeel Equab (of Sense Partners) has publicly stated that overhaul of the Resource Management Act will not be the “silver bullet” for housing affordability, but combined with improvements to the provision of infrastructure-ready house sites, will reduce house prices over time.

Will it make a difference for Māori?

The Resource Management Act 1991 was a landmark piece of legislation in the explicit reference to and recognition of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In addition, the current Resource Management Act and Cultural Impact Assessment and monitoring process are well understood by hapū and iwi Māori. Māori resource management experts have responded positively to the proposed reforms – but with some caution.

The report of the government’s resource management review provides a number of recommendations relating to Te Tiriti o Waitangi me te ao Māori. The recommendations are promising, including strengthening the current Treaty clause from ‘take into account’ to ‘give effect to’, removing legislative barriers to the use of transfer of power provisions and joint management agreements, providing provision for representation of mana whenua on regional spatial planning and joint planning committees, and resourcing for Māori undertaking resource management duties.

Some recommendations should be approached with caution and will require further consultation with hapū and iwi Māori as the draft legislation is developed, including the consistent reference to the ‘principles’ of Te Tiriti (rather than the articles), the proposal to establish a National Māori Advisory Board, and the replacement of ‘iwi authority’ and ‘tangata whenua’ with ‘mana whenua’ (which may not adequately address existing tensions between iwi and hapū level authorities, which can be exacerbated by local councils).

With regards to housing, it’s difficult to say with accuracy where – and to whom – the benefits of the reforms will accrue. Likely, the greatest impacts will be felt in supply-constrained areas (in particular, Auckland), although the Auckland market tends to distort housing markets in surrounding cities, and the increased availability of land and reduced consenting timeframes will likely benefit developers and (optimistically) first-home buyers. However, due to the continued availability of cheap credit (due to low interest rates), likely continued capital gains (due to the slow reduction in house prices), and the continued role of housing as the primary asset/investment vehicle, without specific efforts to de-commodify land and housing, it’s unlikely property investors will be deterred from purchasing multiple properties.

With Māori overrepresented across those experiencing housing insecurity, and with Māori having lower incomes and lower home ownership rates overall, it’s unlikely that the (predicted) slow overall reduction to house prices will make much of a difference for Māori.