On a July day in 2016, at Zealandia in Wellington, then-Prime Minister John Key served an eviction order on the country’s millions of stoats, rats and possums. Over the screech of kākā, he announced Predator Free 2050 (PF2050), an ultimatum that scribed a line in the sand — the end of a nation’s patience with the decimation of its biodiversity.

Almost immediately, arguments broke out over what, exactly, “biodiversity” means. PF2050 has had the collateral effect of galvanising — and at times, polarising — views on what constitutes an “authentic” Aotearoan biota. In short, it has prompted people to ponder which side they’re on.

For decades, thousands of New Zealanders — amateur and professional — have battled to keep what remains of our native wildlife off one of the world’s longest lists of extinctions. But thousands more go into the bush for very different reasons, to engage with an exotic fauna deliberately imported as a target — seven species of deer, the wild pig, goats, wallabies, and the alpine chamois and thar.

PF 2050 is unequivocal: it will only go after possums, kiore, ship and Norway rats, and the three mustelids — weasels, stoats and ferrets. But some in the hunting community have skipped straight to some imagined last page of a manifesto they plainly believe is coming for “their” deer, too. “All wild game including trout existing here now is non native and earmarked for eradication, despite them being brought in over 100 years ago.” asserts Jenese James in a florid piece entitled “Who is driving PFNZ (sic)? (1)

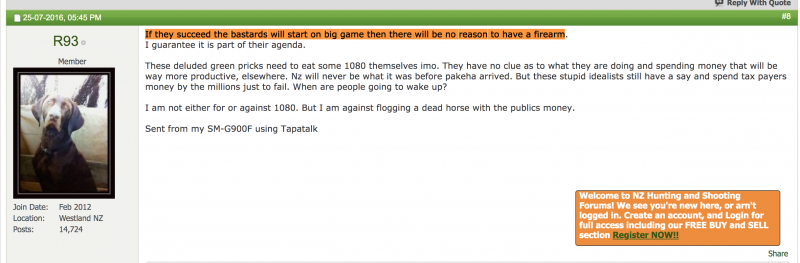

Some on the hunting forums plainly consider PF2050 to be nothing less than an attack on their way of life. “If they succeed the bastards will start on big game then there will be no reason to have a firearm. I guarantee it is part of their agenda,” asserts “R 93” on the NZ Hunting and Shooting site.

Within 24 hours of Key’s Predator-Free announcement, some in anti-1080 circles were inciting sabotage : “If you want to help the environment,” implored one on Facebook’s 1080Eyewitness page, “the best thing you can do is trap rats and possums live and reintroduce them to 1080 dead zones.”

Jamie Steer says there’s no need for dichotomy. “It’s like people prefer the perspective of there being a right and a wrong on this stuff.” A senior biodiversity advisor at Greater Wellington Regional Council, Steer has long maintained that introduced animals (he avoids pejorative terms like “pest”) are, realistically, here to stay, so we may as well learn to love them. Among views that he stresses are strictly personal, and not the council’s, he’s advocated for a fusion biota: one that stops wallowing in loss, and instead recognises the gains: tens of thousands of new immigrants. “I feel we don’t have that balance right around recognising the intrinsic values of introduced species, and the responsibilities we have to both them and native species.”

In Steer’s view, restoration ecology is just resisting change: “At the other end is the ‘accept change’ approach,” says Steer, “where you allow ecosystems to be more self-determining.” Somewhere in there lies a middle way, “where you allow some things to change, and you resist other changes.”

Are there consequences to that? “Absolutely: the most obvious is that, in some areas, species that are valued are locally extirpated.” He accepts that would demand “a measure of acceptance around loss, and that’s a very difficult conversation.”

It certainly is: “That’s just rubbish,” says Kevin Hague, chief executive of Forest & Bird. “The logical consequence of Jamie Steer’s idea is the ongoing homogenisation of global biodiversity. Hague sees a shift in values among New Zealanders, from a “colonising mission — replacing our indigenous biodiversity with a version of Europe’s” — to valuing native biodiversity over introduced. He says that shift might be a function of our search for nationhood: “Maybe some of its resurgence has also been associated with Māori renaissance, and the sense of us as an independent nation, not simply hanging onto the apron strings of mother England.”

Meanwhile, others are still having trouble sorting native from exotic: “Education is key when it comes to the conservation of New Zealand’s endemic marsupials,” claims the Save the Possums Foundation, with oblivious irony.

Brushtail possums are, of course, an Australian species, introduced in the 1850s to seed a fur trade. Their nocturnal nosh-ups have cost tens of millions in lost ecosystem services. They will almost certainly be the first to go — the “small mammal” earmarked for eradication in one of PF2050’s 2025 milestones. Nevertheless, the Save the Possums Foundation are mobilising to wrest the animal from John Key’s death warrant. “The team at SNZPF will not rest until all New Zealanders learn the true nature of our furry friends! Rest assured we will win! Possums will win!!!” predicts the Foundation on Facebook.

Like so many national arguments, this one rages almost heedless to the presence of Māori, and their ancient, singular stake in it. “We all trace our lineage from the atua, or the gods, who created the natural world,” says Tame Malcolm, senior leader on the Biological Heritage National Science Challenge, “and we’re an intrinsic part of that world. The birds taught us how to speak, so when you hear Māori people talking about protecting the birds, they’re recognising that the birds gave us the gift of speech and language. So we owe them one.”

Malcolm carries with him his whakapapa — a genealogy that traces the creation and order of the natural world; thousands of intertwined threads that today represent a woven universe — Te Ao Mārama, the world of light. Whakapapa map that journey of bloodlines, and when they are recounted, they speak of an inextricable bond — wairuatanga — between people and Nature. “We recognise the forest has looked after us,” says Malcolm, “that the waters have looked after us, now we have to look after them — preserve that life force.”

When that life force — that mauri — is depleted, the people are themselves somehow weakened. “If the biodiversity were to return,” says Malcolm, “hopefully, we’d see a return to practices like rongoā, harvesting from a forest in a healthy state. Among different tribes, every bird, every insect, has its own story, but we don’t know a lot of those any more. I’d like to see wildlife return to the marae, and hopefully reawaken the memories of the older people; bring some of those stories back to life.”

Like many Māori, Malcolm is a pig hunter, but wild pigs are now spreading kauri dieback throughout his beloved ngahere, and it’s no contest: “If it was up to me, I’d get rid of pigs in kauri habitat tomorrow, and it wouldn’t bother me. People will say; ‘but those pigs are my food source.’ That’s cool, but — and I know this sounds harsh — they have no right to call themselves kaitiaki, when they’re choosing pigs over kauri.

Hunters are quick to claim that they’re conservationists too, and a great many, such as Fiordland’s Wapiti Trust and the Sika Foundation, donate hundreds of hours to pest control. But the research has been clear now for years that deer, and chamois, and thar, and goats and pigs, do immense harm to the backcountry. “There is nowhere anyone can go in the South Island,” says Colin Bishop, leader of DOC’s Tiakina Ngā Manu pest control programme, “and experience unbrowsed, unmodified beech forest — except for Resolution Island.”

Bishop (who is also speaking here in a purely personal capacity) is a hunter too: “I certainly value being able to go out and get some venison, but I can live without it. It’s not that important to me. What’s more important to me is going out and seeing kākā and mohua — our native species — that’s what rocks my boat. They’re unique to New Zealand, and once they’re gone, they’re gone for good, and losing them reduces the māna of the land, and the people.”

Critics of Jamie Steer’s “fusion” vision of biodiversity point out that the world isn’t short of goats, or pigs, or red deer, but we’re down to our last three dozen fairy terns, and we’ve signed binding international agreements promising to protect them. That because, like 92 other native birds, they live nowhere else on earth, that makes them a global taonga, ours to hold in trust on behalf of the world.

“I wouldn’t worry about contravening the UN Convention on Biological Diversity,” says Steer, “pretty much every country that signed it — including New Zealand — has utterly and completely failed to meet any of its targets. Loss is going to happen whether we like it or not.”

In August, DOC released Te Koiroa o te Koiora, a discussion document asking for peoples’ views on what the next Biodiversity Strategy should prescribe. On its cover, a tagline: “Our shared vision for living with nature.” How, though, given the tangle of dissenting views, do we agree on the weave of our wildlife into the future?

“We need a reasoned, sensible debate,” says Don Hammond, of the Game Animal Council, “that strives for a compromise: about how we manage game animals so that they don’t impose adverse effects, rather than talk of eradication, because that will only polarise people, and it’ll never be resolved.” Hammond says introduced game animals “are part of our landscape: they’re part of what makes New Zealand what it is. We run a real risk when we start talking about dismantling that element of our culture.”

But here’s a thing: by best estimate, there are 65,000 “big game” hunters in New Zealand.(2) Almost 350,000 people do pilates.(3) A million people swim. The natural environment — the ancestral seat of Māoritanga and collective heritage of 4.8 million other New Zealanders — pays a heavy price for the blood sport of a small minority. That raises a fundamental question of democracy that any discussion on the future of biodiversity — if it’s being diligent — needs to address.

“The meaning of backcountry — what it should be — is highly contested,” says Kevin Hague, “and I think that nowadays, given that deer may well be having a still-more profound effect on forest ecosystems than invasive predators, the predominant view would be that it ought not to be a game estate for the few.”

“Part of our culture is the opportunity for anyone to go hunting,” says Hammond. “The fact that a whole bunch of people choose not to, shouldn’t mean that’s necessarily bad.”

“The question is not whether the status quo should continue to exist,” argues Hague. “It clearly should not, because currently, the country’s ecosystems are effectively hostage to the leisure interests of 65,000 people.” Like Hammond, he talks of compromise, which in practice is starting to look like negotiating the removal of four-footed browsers from some sites altogether. “We’ve got all these small remnant bush areas,” says Colin Bishop, “conservation areas and scientific reserves between 200 and 1000 hectares that have deer and pigs and goats in them. There’s a great opportunity to get those browsers out of there and maybe deer fence them. People should be able to experience deer-free areas.”

“I’d love it if we didn’t have pigs and deer,” says Tame Malcolm, “that we could focus on hunting our native species, as we once did. That would be the ultimate long-term goal.”

The conspiracy theorists on the hunting forums may be right — for all the wrong reasons. If PF2050 achieves its 2025 milestone, and possums are banished from the forest for good, people might have reason to wonder why, then, we should continue to tolerate other introduced browsers. As they come to appreciate what advances in pest control technology could make possible, as they see the forests begin to heal, the crosshairs of public concern might well land on deer, and pigs, and goats.

The status quo isn’t serving us well. It needs renegotiating, and Te Koiroa o te Koiora offers a chance to begin.

—

Endnotes

- https://www.infonews.co.nz/news.cfm?l=1&t=0&id=117063

- Kerr, G.N. and Abell, W., 2014, Big game hunting in New Zealand – Per capita effort,

- Sport New Zealand, 2015. Sport and Active Recreation in the Lives of New Zealand Adults.

—

Ways to engage

The Dig does not have a comments section, however Members can Discuss this article in the Scoop Citizen Community Forum (Open to Scoop Citizen Members only)

We will be publishing more journalism by some of NZ’s top environmental journalists right here over the coming weeks. Please subscribe to Scoop Citizen for updates and a chance to engage in the journalism process here.

Click here to join Scoop Citizen >>>

Learn More:

For a good overall summary of the key points of the Te Koiroa O Te Koiora discussion document, see Scoop’s Explainer on the NZBS here and Co-editor Ian Llewellyn’s discussion of the National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity (NPSIB) here. Also check out Scoop’s Biodiversity Full Coverage page here.

You can also learn more about the DOC-led public engagement process, including events around New Zealand here.