“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

– Rumi. 13th Century Mystic Poet

We are in a moment of existential peril, with interconnected climate and biodiversity crises converging on a global scale to drive most life on Earth to the brink of extinction. However, our current worldview and political paradigm renders us incapable of responding adequately due to its disconnected and divisive default settings. These massive challenges can, however, be reframed as a once in a lifetime opportunity to fundamentally change how humanity relates to nature and to each other.

The current engagement around Te Koiroa O Te Koiora, the Discussion Document for a 2020 New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy, and the associated HiveMind engagement on Scoop a great step in this direction. The engagement process gives us an unprecedented opportunity to bring our unique native biodiversity ‘back from the brink’.

Te Koiroa O Te Koiora acknowledges the intrinsic value of our unique nature, the state of crisis it is in, and that the existing 20-year-old biodiversity strategy is no longer fit for purpose under such conditions. Its’ proposals reflect an integrated, wellbeing-based, “all of Government” approach that respectfully and substantively incorporates ao Māori (the Māori worldview).

It also potentially opens the way for bold new thinking and innovative solutions from within and outside Government about how to solve the biodiversity crisis. There are still very real systemic and ideological barriers preventing us from adopting and scaling such solutions. However, to overcome these blocks, we can, and I’d argue, WE must ensure the final strategy is truly co-created from the ground up to reflect a diverse range of perspectives and substantially benefit our communities.

As Farah Hancock pointed out in this excellent summary of the need for a stronger strategy, “hope is not a biodiversity strategy.” True indeed, however, the first step to building a new world is to imagine the future we hope for.

In doing so, we could emulate the great Oceanic voyagers (Māori and Pākehā) that settled Aotearoa and chart a course for a brave new world for biodiversity. This process could provide much-needed hope, inspiration and leadership for a global recovery and a “New Deal for Nature” ahead of the critical 2020 international biodiversity convention.

Biodiversity on the Brink – Counting the losses

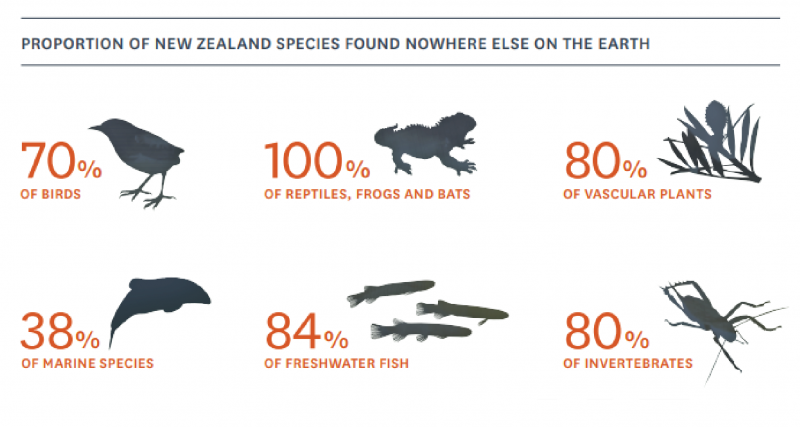

“NZ is home to species found nowhere else but biodiversity losses match global crisis” – Robert McLachlan and Steven Alexander Trewick

Short for ‘biological diversity’, biodiversity describes the variety of life on earth. As Te Koiroa O Te Koiora defines it, it is “the variety of all biological life – plants, animals, fungi and microorganisms – the genes they contain and the ecosystems on land or in water where they live.” In other words, biodiversity in Aotearoa is not just about kākā and kōwhai, or rats and radiata – it is about the interconnections between various species and systems.

This national engagement opportunity comes at a critical time for the biodiversity of Aotearoa and the planet. There is now a scientific consensus that the rapidly heating climate and habitat destruction in the Anthropocene (current geological era), have triggered “The Sixth Mass Extinction.” This is an extinction event on a scale not seen since the one that killed the dinosaurs and allowed our native biodiversity to thrive in the vacated niche.

The landmark 2018 Living Planet Report indicated that more than half of the planet’s wildlife has vanished in the last forty years. The canary in the coalmine – the global insect population – has declined by up to 90 percent in what is being termed an Insect Apocalypse that will have massive flow on effects.

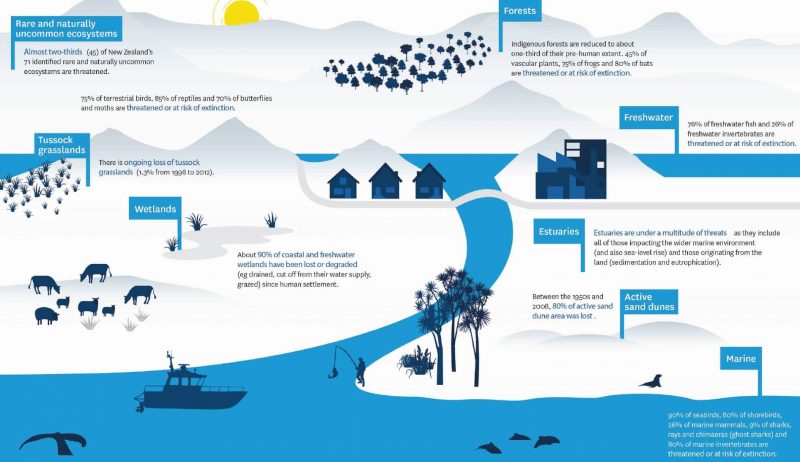

Sadly, New Zealand biodiversity losses match this global decline. The Environment Aotearoa 2019 report, showed a worsening trend for native species, with just under 4000 threatened with, or at risk of extinction, and an acceleration in the loss of native plants. We have the largest number of threatened species of any nation. Even more concerning, both reports exposed data gaps due to lack of science funding, which hampers understanding of biodiversity and how these crises will impact it.

Converging Crises

‘If the land is sick, you are sick’ – Aboriginal ProverbBiodiversity touches human lives in many ways – but more critically – we impact it, and mostly, not in a good way. Basically, everywhere modern industrial civilisation spreads, the diversity of non-human life and ecosystems is rapidly disappearing or diminishing.

We are experiencing a perfect storm of converging crises of biodiversity loss, and Global Heating, forming a self-reinforcing feedback loop. This global systemic failure of our current systems on multiple levels – ecological, social, political and market – is essentially driving us towards extinction.

The United Nations stated in May, that preserving biodiversity is vital to reverse climate change. A special UN Climate Change report released on Friday by the IPCC, also states that “land use” (largely agriculture, forestry and land clearing) contributes 22% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Such destructive land use patterns are in large part responsible for accelerating biodiversity loss.

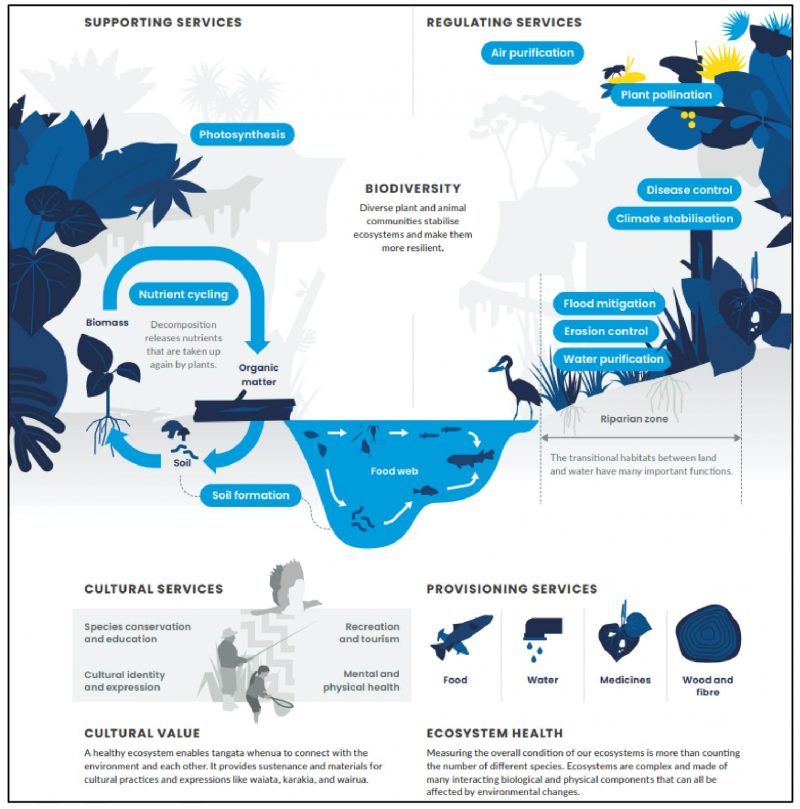

This is because biodiversity is the superpower that allows nature to effectively do the jobs that make the earth a habitable planet for all life. Networks of intact ecosystems working synergistically as a whole, perform many crucial tasks we rely on, far better and more efficiently than any human built technology or planted environment ever could. Without biodiversity, humanity will quite simply be lost.

Whether we accept it or not, humans are part of this interconnected whole we call nature, as all life on earth is very closely related evolutionarily, chemically and biologically. However, the dominant worldview of modern industrial capitalist society, in placing us as separate from, and above nature in the ‘chain of being’, is resulting in our destructive actions towards each other and nature.

Continued disruption of nature’s networks by such disconnected thinking, will cause ongoing catastrophic impacts on our food systems, climate resilience, and ultimately the continued physical and spiritual thriving of humans. A report from the Nature For All Network is one of many highlighting the beneficial effects “connecting to nature” has on our wellbeing, communities, economies, and physical and mental health.

Despite this undeniable preponderance of evidence, it seems few people are even aware of what biodiversity is, let alone, why they should care about it. Almost 50% of Australians surveyed recently, for example, demonstrated no understanding of the accepted definition.

The level of awareness is likely slightly higher in NZ, given greater Government action, education and investment in conserving our unique native biodiversity over successive decades, but it is clear from our actions that we are not aware as we should be of how significantly biodiversity loss impacts our future.

There is a field…

“The visions we offer our children shape the future. It matters what those visions are. Often they become self-fulfilling prophecies. Dreams are maps.”

― Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

So is there hope for life on this green speck upon a pale blue dot we call Aotearoa?

As Sagan wrote, “Imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were. But without it we go nowhere.” We cannot go back time, however this is rare chance to dream a new vision and chart a course to a ‘world that never was’ for biodiversity in Aotearoa.

So please bear with me and take part in this thought experiment to imagine and re-imagine the future of biodiversity in New Zealand.

It’s 2070, somewhere in rural NZ… there is a field…

… it is a scorched earth of lifeless soil, weeds and abandoned corporate monoculture farms destroyed by competitive, intensive agriculture. The field, siloes and surrounding community are empty of all but rats, with rural industry and livelihoods gone. It is surrounded by eroded hills of silent and dying pine plantations ravaged by climate-induced wildfires and infections.

Farms and forests have leached sediment and nitrates into local rivers for decades rendering them anaerobic, toxic and devoid of native mudfish (whitebait), eels and kōura (crayfish), only a few adaptable introduced species remain. Rivers flow to acidic and polluted wetlands and coastal seas with destroyed reefs and beds leaving no habitat for fish or marine mammals. GMO food is grown in corporate vats and vertical farms in cities surrounded by barren urban sprawl covering once-fertile soils.

There is a last-ditch mass conservation effort and geoengineering climate action and exotic landscape remediation once the tech and political will and finance finally aligns. A few remaining hardy intact indigenous habitats and species cling on in Zoos and fenced conservation zones far removed from people. Throw in a migration problem due to ravenous penguins fleeing a vanished Antarctica and empty seas (or worse Australians escaping a desertified wasteland and Mad Max-style demolition derby) and we have a dystopian “don’t know what you’ve got till its gone” future.

Now re-imagine. It’s 2070, somewhere in rural NZ… there is a field…

… The dawn chorus is deafening as the field is thriving with all of the native birds, reptiles, and insects still alive in 2019. It has living soils full of microbiota, fungi, and invertebrates. It is interwoven with agroforestry of fruit and nut trees, and vines. Livestock forage amongst trees eating weeds and fertilising.

The field is interwoven with strands of cooperatively managed, sustainably harvested native forests, and ‘close to nature’ plantation forests for use in local industry. Hemp fields and flax swamps replace plastic and cotton imports and provide paper, building materials and local industry in food, fibre and medicine.

Humans work, play, and study in the field, and bees from local hives busily pollinate and provide native flora honey. Community gardens, allotments and rongoā (health) gardens cluster around affordable eco-communities providing medicine and low-cost, healthy food.

A pristine, thriving and expanded, National Park flourishes in the distance providing recreation and tourism opportunities. Drinkable rivers flow from still snowy peaks through restored wetlands to clean seas full of diverse marine life providing sustainably caught kaimoana. Māori and Pākeha act as collective Kaitiaki (stewards) and collectively preserve Tikanga Māori (customary ways), history and environmental practices and open-minded scientific inquiry.

Community level participatory democracy makes decisions on an entire landscape level and local communities benefit from economic activities. ‘Community Conservation Corps’ provide stable jobs, volunteering and educational opportunities for all. Rapid sustainable transit connects the field to urban centres every bit as flourishing with life and abundance, allowing urban dwellers to enjoy the field and trade with the local community. Let’s call that “the Nailed it” future.

The Opportunity – Reimagining Nature

The point of this exercise was not to make realistic predictions, to lay blame on individuals, groups or institutions, or to vilify exotic species as a rule. Rather it was:

- To remind you that the cognitive freedom to collectively re-imagine the world we want is a more powerful tool than we give it credit for, and our biggest asset.

- To highlight both the challenges, and the opportunity raised by the interconnections of nature and the crises we face.

- To reflect on how different worldviews (ways of thinking about our world) shape the way we collectively relate to, and impact, our biodiversity and ecosystems.

So which future are we heading for? – Disconnected-dystopian, or interconnected-utopian? Perhaps a bit of column A, a bit of column B? Our future may lie in some alternative reality altogether, as we still have an opportunity to shape it.

‘Te Koiroa O Te Koiora’ is a key step to building this ‘brave new world’ for biodiversity in Aotearoa. Both the DOC-led engagement process, and Scoop’s HiveMind public engagement on biodiversity, aim to uncover shared values and build visions around nature.

This is not fluffy language or sentimentality – it is from such mutual grounding in shared language, values and understanding that we can hope to see the perspectives of ‘the other’ and realise that deep down, they are the same as our own. Only through such wide framing is it possible to create a new worldview and inclusive policy settings that work for everyone, and for nature for well beyond 50 years.

Nature is the solution

Toitū te Marae o Tāne, Toitū te Marae o Tangaroa, Toitū te tangata / Protect and strengthen the realms of the Land and Sea, and they will protect and strengthen the People.

– Māori Proverb

Te Koiroa O Te Koiora begins the work of meeting these challenges by recognising that our unique biodiversity, and us with it, are in existential peril.

It highlights the impacts that disruption of natural interconnections has on the prosperity of our nation and the potential of nature to meet these challenges. Importantly it takes conservation beyond the borders of conservation areas and into the real world – onto private, and Māori land.

The proposals address the need for innovations that have the potential to address climate and biodiversity simultaneously such as Nature Based Solutions to climate change (eg using forests or wetlands for carbon capture), and landscape-scale interventions. Such solutions have the potential to deliver 30% of the climate solutions we need by 2030, while also helping reverse biodiversity loss.

But do the proposals go far enough? Economist Joseph Stiglitz has commented that Climate change is our third world war. He and others believe that our response needs to be on the scale of what a recent study terms “a Global New Deal for Nature” to address these interconnected crisis.

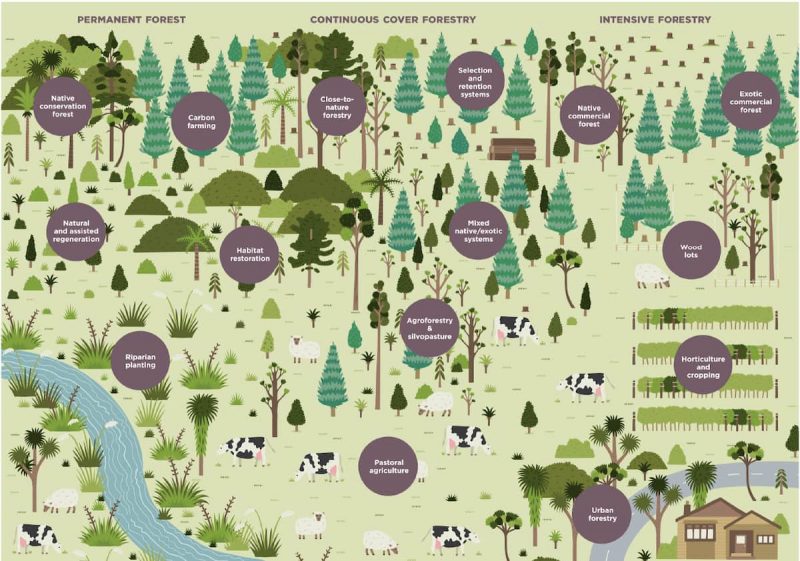

There is rapid progress globally in more biodiversity friendly land use methods we can adopt such as: Silvopasture (combined livestock and forestry), Agroforestry, Biomimicry, Regenerative Agriculture, Hemp farming, Green Urban Design, Re-wilding nature and even Blockchain Smart Contracts to incentivise conservation.

However, to drive this change we cannot solely rely on market-based solutions or corporate subsidies within the existing inequal economic paradigm. We need a genuinely collaborative and people-centred approach to productively engage communities through innovations like Community Land Trusts, cooperative agriculture, and the Circular Economy advocated by Stiglitz and Kate Raworth’s “Donut Economics“.

Perhaps a more appropriate level of response to these circumstances is to declare a “Biodiversity Emergency” and forge a new deal for agriculture. We could even revive ideas such as Community Conservation Corps to provide full regional employment and meet these crises head on.

To see what can be achieved with coordination and investment, we only need look at China’s massive projects to regreen deserts globally and create sustainable local industries through community partnerships. NZ and China co-chairing the Nature Based Solutions Coalition at the upcoming Climate summit provides real potential for cross pollination on this approach to restoring what has been lost.

A genuine community effort like this requires leadership, sufficient investment and policy settings that remove barriers to communities adopting, financing and scaling these solutions. However, it is worth it. Harnessing the passion and energy of New Zealanders through more distributed and cooperative land use and economic opportunities could create abundance and true prosperity by improving the lives of all New Zealanders in the process. The only way to achieve that is an ideological or paradigm shift.

A Brave New Worldview

“Ko au te ao, ko te ao te au – I am the world, and the world is me.”

– Māori Proverb

We are a product of our environment, however, in the Anthropocene – our environment is a product of our worldview. Most excitingly, Te Koiroa O Te Koiora builds on the pioneering progress in affirming rights of nature and indigenous self-governance in Te Urewera and the Whanganui River by integrating key elements of te ao Māori (the Māori worldview).

Ao Māori sees Nature as imbued with Mauri (spirit) and intrinsic value and recognises the need for Mātauranga Māori, (traditional knowledge) and Kaitiakitanga (stewardship) arising from this inseperable interweaving of natural systems and humanity. The emphasis this ao Māori worldview places on the holistic wellbeing of current and future generations, also aligns well with the Government’s Wellbeing Budget approach.

This interwoven worldview aligns with cutting edge science in quantum relativity, systems thinking and with land use policy recommendations from sources such as a 2002 Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Report: and David Hall’s excellent 2018 paper The Interwoven World for AUT’s The Policy Observatory.

We urgently require a new co-created vision, worldview and narrative around our relations to nature and each other. This new narrative must move “beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing” and the idea of “the other” to find the common ground that unites us as all connected living beings.

It must recognise our intrinsic connections to nature and reliance on it for our future thriving. This is why it is so important that a wide range of us participate in this engagement process and educate ourselves about why biodiversity matters.

To find that common ground we could do worse than to heed the words of Rumi, in the remainder of the verse we began with:

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,there is a field.

I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass

the world is too full to talk about.

Rumi

Learn More:

For a good overall summary of the key points of the Te Koiroa O Te Koiora discussion document, see Scoop’s Explainer on the NZBS here and Co-editor Ian Llewellyn’s discussion of the National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity (NPSIB) here. Also check out Scoop’s Biodiversity Full Coverage page here.

We will be publishing a series of in-depth journalism by some of NZ’s top environmental journalists right here on Scoop over the coming weeks. Please subscribe for updates and a chance to engage in the journalism process here.

Learn More:

For a good overall summary of the key points of the Te Koiroa O Te Koiora discussion document, see Scoop’s Explainer on the NZBS here and Co-editor Ian Llewellyn’s discussion of the National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity (NPSIB) here. Also check out Scoop’s Biodiversity Full Coverage page here.

We will be publishing a series of in-depth journalism by some of NZ’s top environmental journalists right here on Scoop over the coming weeks. Please subscribe for updates and a chance to engage in the journalism process here.

You can also learn more about the NZBS Discussion document and the DOC-led public engagement process, including events around New Zealand here.

In part two I will discuss how our dominant inherited worldview influences our thinking and systems. I will explore how the exciting alignments between cutting edge science, new ideas about collaborative economics and indigenous worldviews can help overcome this paradigm.