Header Image: Tuatara. Photo: Cameron Houston, DOC.

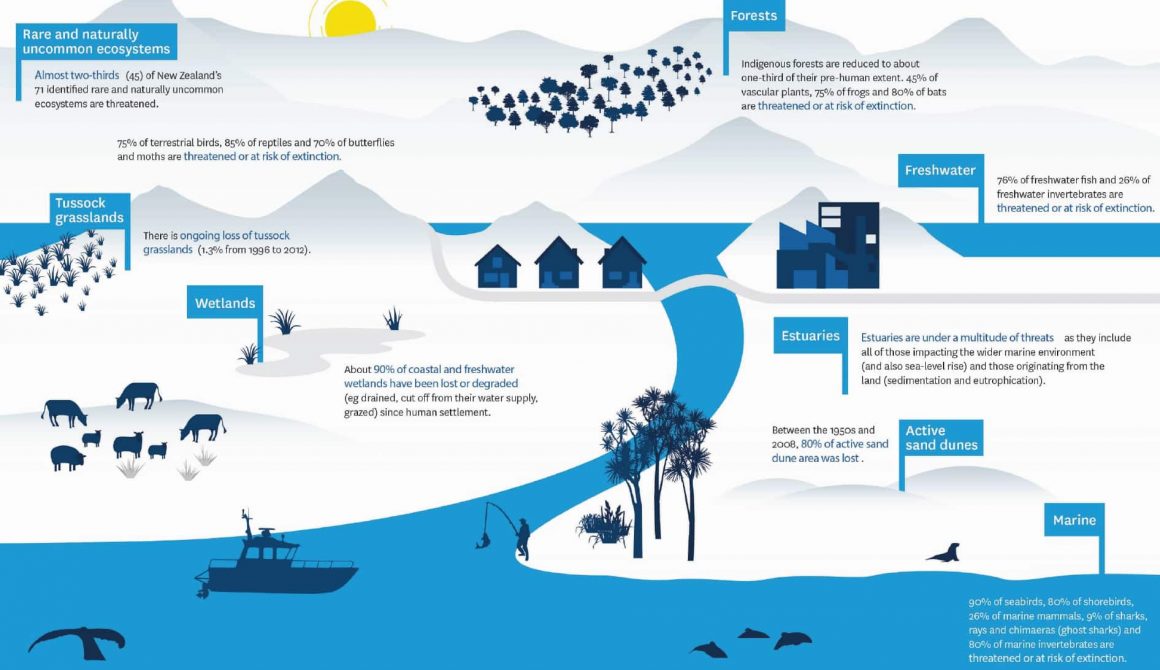

Four thousand and sixteen species. That is the staggering number of Aoteaora’s species currently threatened or at risk of extinction. It’s also the number that gives us the unenviable distinction of being the country with the highest proportion of threatened indigenous species in the world.

As a nation whose identity is strongly linked to our national heritage, it’s surprising that we’ve let things get so bad for our biodiversity ¬– a collective term for the variety of life that calls NZ home.

Back in 2000, the Department of Conservation (DOC) released a 20-year plan to help our nature thrive. Despite the promise of this inaugural National Biodiversity Strategy, which aimed to “turn the tide” on biodiversity decline, our native species have continued the sad slide towards extinction. Ecosystems from coastal estuaries to tussock grasslands continue to disappear beneath our collective human footprint.

“The scale of biodiversity decline in New Zealand is such that unless we really up the game, in terms of magnitude and extent, we will just continue this slide,” says Professor Bruce Clarkson, an expert in ecological restoration and Deputy Vice-Chancellor Research at the University of Waikato.

But in spite of the dire outlook for our biodiversity, there’s a spark of hope glimmering in the eyes of conservationists. Across the country, we’re seeing a shift. Over the last decade, community groups have cropped up like weeds, with concerned citizens keen to tackle the challenge of ecological restoration on their patch.

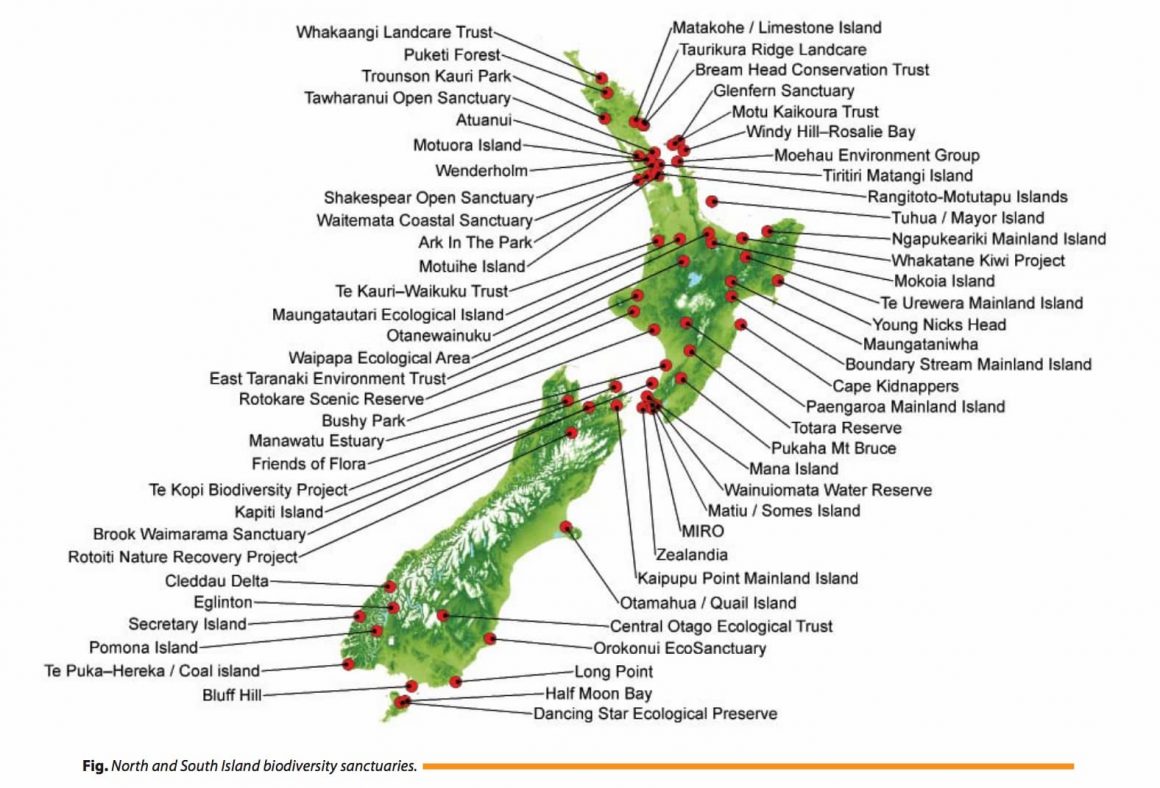

There are backyard trapping networks doing their bit for Predator Free 2050, farmers planting native trees along their waterways, and iwi protecting whenua rāhui. There are 62 biodiversity sanctuaries across 56,000 hectares, with around two-thirds of them community-led. There are citizen scientists counting birds in their backyards and landowners conserving habitat in 3,500 Queen Elizabeth II National Trust covenants.

It’s increasingly clear that a government agency alone cannot combat the biodiversity crisis successfully. These grass-roots initiatives are a growing resource in the conservation toolbox.

Issue 20 / June 2012 – Community Conservation

Wild wellbeing

There’s good reason to latch on to the community approach -– not just for the on-the-ground work volunteers undertake, but also for the benefits it bestows on individuals.

Connecting to nature makes us happier and healthier, according to a growing mountain of evidence. There are even indications that nature can make us more generous, cooperative and kind.

Experience in nature makes us more connected to place, which in turn makes us want to care for and protect it. And to tackle the biodiversity crisis, we’re going to need people who care.

But not everyone has a chance to regularly visit the national parks that make up our outstanding conservation estate. And how do you care about something that you can’t see and experience?

It’s a case of bringing conservation to where the people are. “If you’re going to bring people with you, you’ve got to be doing stuff which is relevant to them and their own backyard,” Clarkson explains. This realisation has propelled him and his ecological restoration work into cities and peri-urban areas.

Power to the people

“Supporting on the ground action Community conservation has grown significantly in the last few decades. Community restoration groups, backyard trappers, coastal and marine protection advocates and the sanctuary movement have changed the face of biodiversity management.”

Te Koiroa o te Koiora discussion document

Community conservation features substantially in recent thinking in the Government’s Te Koiroa o te Koiora discussion document and draft proposed National Policy Statement on Indigenous Biodiversity. These will inform a new (and hopefully improved) 2020 National Biodiversity Strategy.

After the failure of the 2000 Biodiversity Strategy, it’s obvious that a new approach is needed. However, by itself, community conservation falls short. A 2018 research paper found that evaluating community projects’ effectiveness was difficult, given their lack of clear and measurable goals.

What’s more, small projects scattered piecemeal over the country lack the scale and coordination to be truly transformative. For example, the flowering and fruiting of plants that sustain our native birds are often staggered, with progressive fruiting over the landscape providing a moveable feast. Our birds need more than just a remnant patch of kōwhai to thrive.

Perhaps, then, the solution lies in simply thinking bigger.

“For the survival of New Zealand biodiversity, we can’t treat any one environment in isolation,” says Clarkson, “They are all contributing to how biodiversity is maintained at landscape scale.”

Rewilding the regions

So how can we bring together the efforts of community groups to achieve this broad-scale goal? Many have landed on the idea of “regional conservation hubs” that put the theory of collective impact into practice.

Collective impact is a framework for comprehensive change. It’s been used successfully in the social and health sectors, from boosting educational attainment to preventing obesity in a community. In essence, collective impact involves bringing stakeholders together in a structured way, establishing a shared vision and method to measure outcomes, and continuously communicating as an agenda is implemented.

This is where regional hubs come in – they connect groups, facilitate sharing of expertise and practice strategic planning to make conservation more impactful.

One of the longest-running examples of a regional “conservation hub” is the Waikato Biodiversity Forum, which has been in action since 2002. The Forum’s members include 450 individuals and groups across agencies, community groups, research organisations, private landowners and plant nurseries. The Forum runs workshops and events, and connects groups to one another, allowing them to share knowledge, skills and experience.

“We’re very much an enabling organisation,” says Forum coordinator Sam Mcelwee, “We try to facilitate activity that’s already happening and try to add value. People can come for advice – ecological or funding – utilising the network that we have.”

The Forum has been ahead of the curve with the idea that “no one agency, sector or element of society has all the answers to biodiversity issues”. It may seem simple, but an approach that emphasises “efficiency through collaboration” is only now being actioned across New Zealand.

From the more than 15 years’ worth of work by the Waikato Biodiversity Forum, we know there is value in this approach.

“The community here is well-connected and quite cohesive,” says Mcelwee, “Connecting digitally and meeting in a real physical sense, it’s a huge thing that brings down a lot of boundaries and creates opportunities for people to start working together – and feel less isolated as well. Knowing that there is some kind of support and collective is vitally important.”

Clarkson is a supporter of the regional hub approach. In a 2005 review of the original National Biodiversity Strategy, he and co-author Dr Wren Green “strongly landed on this need for a more collaborative approach at regional scale”.

“This is about how government agencies support and enhance community activity in a very positive, enabling way by helping them with resourcing, by helping them with technical advice, and of course by helping them with funding,” he says.

Now, regional conservation collectives are becoming more ambitious in their goals, actively pursuing ecological restoration over large tracts of land. Leading the charge is Biodiversity Hawke’s Bay, an umbrella group tasked with implementing the Hawke’s Bay Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.

“I think Hawke’s Bay seems to have crossed a threshold where the government agencies are prepared to invest in the community to make this stuff happen,” says Clarkson.

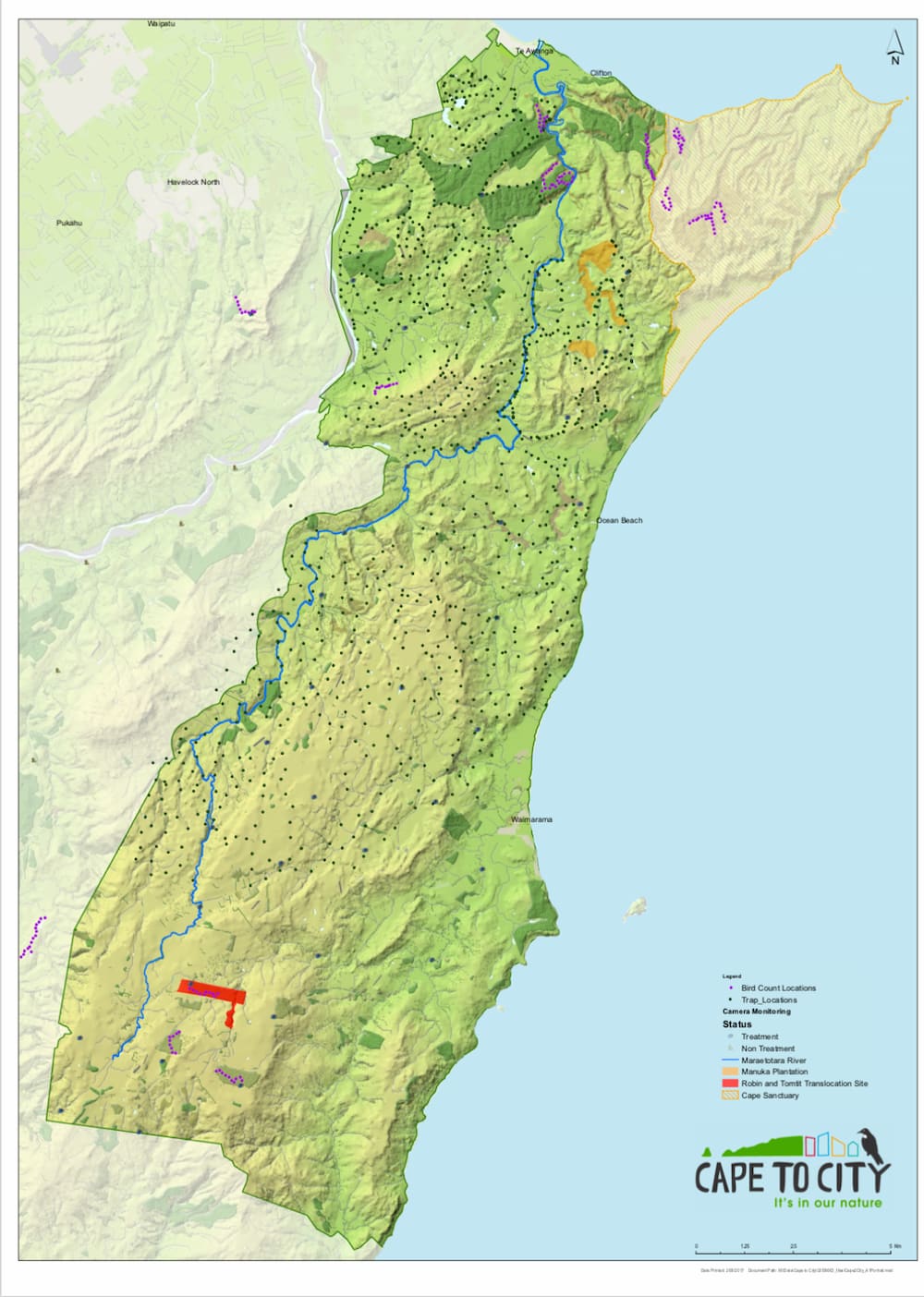

In particular, the Cape to City project is a strong example of landscape-scale conservation occurring in the region. Cape to City encompasses 26,000 hectares of land, most of which is farmland, and includes a sanctuary enclosed by a predator-proof fence. The project engages iwi, hapū and private landowners to implement pest control, habitat restoration and water quality improvement.

In a similar vein, enhanced connectedness was one driving force behind the creation of the

Predator Free New Zealand Trust in 2013. In many ways, it’s comparable to the Waikato Biodiversity Forum or Biodiversity Hawke’s Bay – just with a focus on a single issue (pest control) across of all New Zealand (instead of just one geographical region).

“There were all these community groups working somewhat siloed,” explains Jessi Morgan from the Predator Free New Zealand Trust, “So they weren’t sharing learnings or information and access to best practice was really hard. We’ve just tried to remove those barriers as much as we can for community groups and make it really easy.”

Collaborations at the heart

Naku te rourou nau te rourou ka ora ai te iwi

Traditional Māori Whakatauki (Proverb)

With your basket and my basket the people will live

Collaborations are at the heart of collective impact theory and regional conservation hubs. They’re also central to DOC’s new partnerships approach, as realised in the Kotahitanga mō te Taiao Alliance. Kotahitanga is focused on the top of the South Island and covers Marlborough, Nelson, Tasman, Buller, the West Coast and Kaikōura.

The Collaborative Approach

The approach has four parts, as Martin Rodd, DOC Partnerships Manager described in an interview. It begins with building an alliance between iwi, local government and DOC. This combines iwi’s connection to place and traditional knowledge with local government’s tools and frameworks, and DOC’s scientific and technical expertise. “When you combine those three together, that’s a pretty powerful combination to have around the table,” says Rodd.

This sentiment is echoed by Richard Witehira, from Rāwhiti 3B2 Ahu Whenua Trust: “Kaitiaki must lead the biodiversity strategy where applicable in collaboration with government departments, NGOs and community groups,” he said at the Wellington launch of the Te Koiroa o te Koiora discussion document, “That’s the way of the future. Collaboration is cost-effective and it’s inclusive, not exclusive.”

Of course, there are challenges in bringing together groups with diverse (and sometimes competing) views and interests. “We can take some time to get to consensus,” says Rodd of his experience chairing Kotahitanga, “But my observation has been that we’ve always been better off by working it through … We’d be faster alone, but we’ll go further together.”

Other steps in DOC’s partnerships model, according to Rodd, include building capacity and capability in communities to carry out conservation activities, and identifying the right places in which to work for maximum effectiveness across the landscape.

These steps are collaborative, not dictated by agencies alone. It is important that the interests of the community are represented, says Morgan, “They need to be community-led hubs, not agency-led … flexible as opposed to set from the top-down.”

Finally, in DOC’s four-component modus operandi, there’s the question of funding.

Show us the money

Funding has always been a pressure point for conservation. Ecological restoration is an endeavour that relies heavily on the goodwill, time and effort of volunteers. Although the Te Koiroa o te Koiora discussion document identifies “an increase in philanthropic funding and increased awareness and contribution from business and industry”, those on the ground still say that securing money is the toughest task for community groups.

“I think it’s really hard out there … volunteers spending all their time applying for funding for $2,000 that they’ve got to write all these reports about is just inefficient,” says Morgan.

Mcelwee also laments the “complexity of applying for funding”, saying that, “The amount of time and energy it takes to apply for those funds is a big barrier.”

“If the expectation is that communities are going to do the majority of the work to enhance biodiversity, then there has to be appropriate funding. The funds at the moment are being oversubscribed. The demand is growing and the amount of funding needs to reflect that.”

Part of the solution may lie with the regional hub or partnerships model, Kotahitanga-style. Kotahitanga has experimented with approaching funders such as the Rātā Foundation with a proposal, rather than applying for a fixed grant.

“We ask, ‘Would you be prepared to proactively invest in the capability and capacity of this hub?’” explains Rodd. This gives the hub the financial resources it needs to implement its action plan without having to continuously apply for small grants. The centralised hub model also breaks down many of the administrative barriers and time sinks that typically burden community groups.

“What it avoids is duplication,” explains Rodd, “Imagine every single group having to think about: the funding application, the monitoring, having a legal structure in order to set up to receive the funding… All these challenges! Whereas if you just have a really well set up hub, then they can make it so much easier for those groups to get on and do what they love doing.”

Compared to other charitable causes, environmental and conservation organisations rely more on donations and bequests, and have one of the highest volunteer to paid staff ratios.

Back in 2007, a survey of 201 New Zealand community conservation groups reported a total of 6,232 volunteers contributing 174,812 hours of labour in a single year. At the time, this contribution corresponded to NZ$15.8 million. Today, these figures are likely to be significantly higher. In 2017, there were more than 730 environmental and conservation charities in New Zealand.

Can we really expect to solve the biodiversity crisis if we think of it as something we do for free on the weekends?

Connecting biodiversity to the economy

While “community ownership of biodiversity action” is a great concept, we can’t reasonably expect communities to do it all. Likewise, we can’t let agencies off the hook for the tricky stuff like captive breeding of threatened species or back-country trapping across rugged and remote terrain.

But beyond DOC and weekend tree planting, we need a more substantial shift – one that connects biodiversity outcomes to economic opportunity, instead of placing them at odds.

“The bottom line is: unless biodiversity and restoration are connected to the economic scenario, and in particular to providing work opportunities for people, then I don’t think we’ll get far enough in the solution,” says Clarkson.

While the Te Koiroa o te Koiora discussion document acknowledges the ongoing tension between economic prosperity and biodiversity protection, it isn’t clear how the two can be connected in practice. How can we make biodiversity work for communities?

Tourism offers one option, as Witehira mentions in his address at the Te Koiroa o te Koiora launch, saying, “There is huge economic potential for the QEII Trust developing an indigenous-based ecotourism product to capitalise on increasing biodiversity values.”

In his local community, he says that four jobs became available thanks to biodiversity work, “four more than ever before in a small community shackled by welfare dependency and high unemployment rate”.

This is good news, but how can the conservation movement support communities long-term? Ensuring that these economic opportunities are sustainable is an overlooked part of the equation.

Part of the issue lies with our value frameworks, which fail to account for the contribution of ecosystem services to the economy (and to human health). “Treating biodiversity as a key infrastructure, just like roading, I think that that’s where the future is,” says Mcelwee, “It’s all about value.”

But reorienting an entire system is no easy feat.

The future of biodiversity in New Zealand

We’re at a turning point. According to experts, all the ingredients are there. The stage is set, we know the lines: community conservation, collaboration and landscape-scale restoration. They have huge potential to bring life back to our native ecosystems. Can we pull it off?

Rodd is optimistic: “If we keep going down this road of working together, being clear on outcome, and we enable people to join up and align to those outcomes, it’s going to go off!” he says.

Clarkson, too, is hopeful that this time, we’ll get the National Biodiversity Strategy right.

“If we can do the sorts of things that are being articulated in the new strategy and in the draft National Policy Statement, we’ll have a good shot at it,” he says.

“It does mean that everybody has to take some responsibility here – landowners, city-dwellers, government agencies – all of us are responsible for achieving this goal.”

Looks like it’s up to us what future we choose to build. Whether it’s a future that’s good for people and communities and for our 4,016 threatened species, only we can decide and take action.

—

Ways to engage

The Dig does not have a comments section, however, Members can Discuss this article in the Scoop Citizen Community Forum (Open to Scoop Citizen Members only)

We will be publishing more journalism by some of NZ’s top environmental journalists right here over the coming weeks. Please subscribe to Scoop Citizen for updates and a chance to engage in the journalism process here.

Click here to join Scoop Citizen >>>

Learn More:

For a good overall summary of the key points of the Te Koiroa O Te Koiora discussion document, see Scoop’s Explainer on the NZBS here and Co-editor Ian Llewellyn’s discussion of the National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity (NPSIB) here. Also check out Scoop’s Biodiversity Full Coverage page.