Technologist and climate activist Jon Leighton writes about the climate and ecological crisis, and the folly of putting our faith in activism or technological solutions to deliver us from these crises. Instead he is now focusing on re-localisation and re prioritising real, tangible skills and becoming less dependent on the monetary economy.

Listen to the audio version of this article below:

Right now the world is grappling with COVID-19, but over the past year or so I’ve spent quite a bit of time trying to make sense of the worsening ecological crisis and what it means for my life.

Some history

All the way back in 2007, I first learned about climate change and the havoc and suffering that it was predicted to bring. I quickly got swept up in the UK grassroots climate change protest scene, and had the perhaps naive view that the movement was building, the case was only getting stronger. With enough effort and intention, together we would turn the ship around.

I clung onto that belief and tried to be part of the solution, but how that looked in my own life changed over the years. I burned out on activism, and spent five years working on building Loco2 (now Rail Europe), a business founded with the explicit intention of making low-carbon rail travel the default alternative to high-carbon short-haul flights. I believed in the potential for technology to change our course, and that we’d get there, sooner or later. We had to because the alternative was unthinkable.

As the years have ticked by, it has become harder and harder to hold on to that belief. All the evidence suggests that the ship is not turning. Year on year, the warnings are getting more desperate and more shrill, as though waving our arms in the air ever more frantically will do the trick.

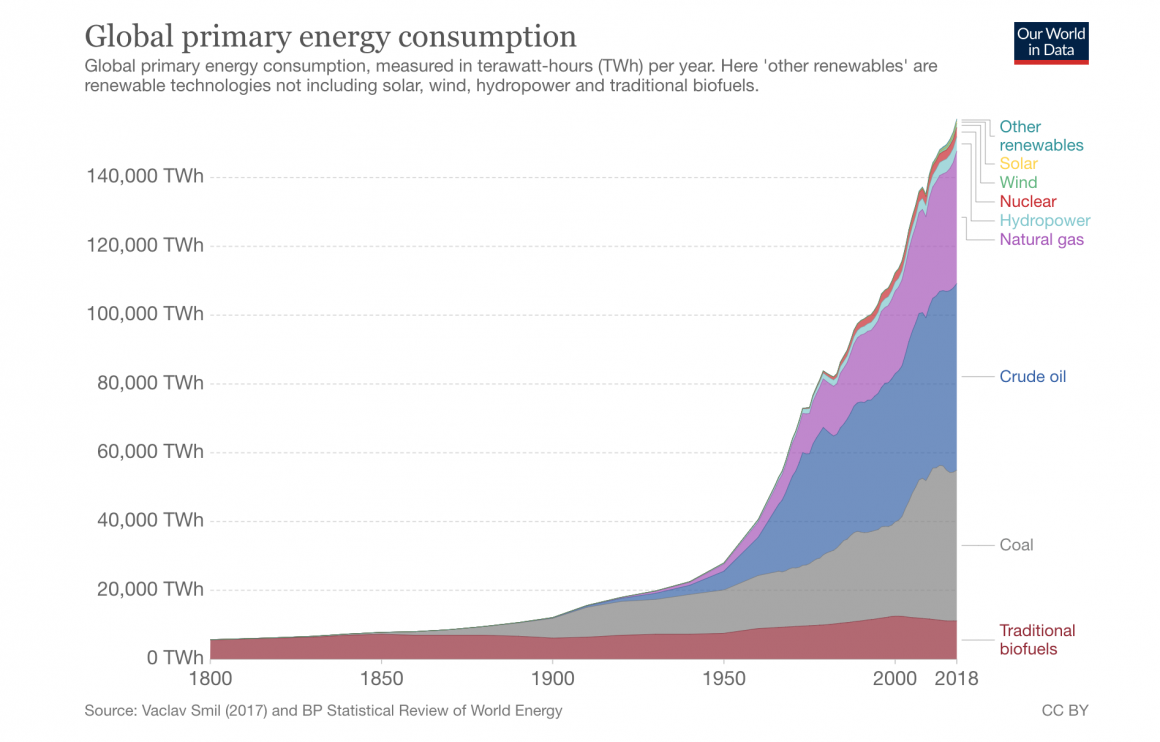

Right now though, we’re in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is thought to be causing the biggest ever drop in global carbon emissions due to the large-scale shut down of economies across the world. So it’s staggering to realise that despite this drop, we’re still on track to emit more than we did just a decade ago. While the analysis is still quite uncertain, it suggests that COVID-19 has made barely a dent. If we get back to “normal” after the pandemic, we’ll just continue that relentless march: up and to the right.

Even a 10% fall in global fossil-fuel emissions would see […] a higher total than in any year before 2010. Any emissions cuts in 2020 alone will, therefore, have little impact, unless they are followed by longer-lasting changes.

Carbon Brief

Faith in technology

There have been huge advances in “clean technology” over the past decade. Renewable energy has become massively cheaper and more abundant. Electric vehicles are gaining momentum. The demand for coal is stagnating.

Yet globally, carbon emissions have shown no sign of doing anything but rise. Each year, we are continuing to burn more than the previous year, despite the growth in renewables. The renewables aren’t replacing fossil fuels, they’re augmenting them to continue feeding our society’s insatiable appetite for energy. (Some richer countries have achieved modest emissions reductions but mostly by outsourcing manufacturing to countries like China.)

The political structures that we have right now are obviously incapable of creating the changes that are needed, so the idea that technology can be the solution is rather alluring. If we can’t change politics, then at least we can put our faith into creating technology so amazing that everything else will just fall into place.

But that mindset relies on believing that the problem is that we don’t have enough technology, or that the technology needs to be better. I don’t believe that’s true. The best solar panels and the most efficient cars won’t help at all if the underlying conditions that got us into this mess remain the same. Unless we find ways to live that don’t require ever more energy and resources, the clean tech will never be enough.

Acceptance

2019 was the year I finally allowed myself to think: maybe it won’t be OK? What then? It has been liberating to let go of the exhausting belief that we have to stop this, in spite of the fact that I have almost zero power to change anything.

Of course, the outcome is not binary. 2°C warming and 6°C warming are both terrible, but one is definitely more terrible. Impacts are already being felt across the world, especially by the poor, but it’s still important to try to avoid worse impacts in the future.

The shadow of hope is fear: maintaining hope for something despite contradictory evidence can be a mask for actually not wanting to face the fear of something else.

Accepting that some huge and devastating impacts are likely within my lifetime allows me to start asking how I should relate to that. Can I be OK with leaner times ahead? Can I find purpose and meaning in the context of escalating suffering? What is most important to hold on to, and what can I let go of? What skills will be needed in the future, and how can I gain them now?

So much of what we’re told should give us hope looks more like toxic hope – waiting for an abuser to change their behaviours when they’ve given us every reason to believe they never will. The longer we cling on to toxic hope and unfounded positivity, the further away we are from ending the oppressive and abusive relationships that underpin this ecological and social crisis.

I’d rather be called a climate pessimist than cling to toxic hope by Philip Marrii Winzer

Earth care, people care, fair share

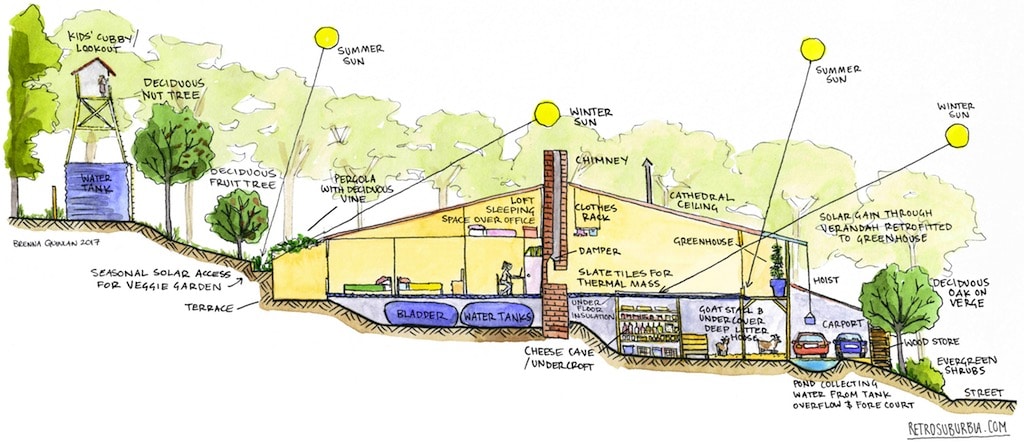

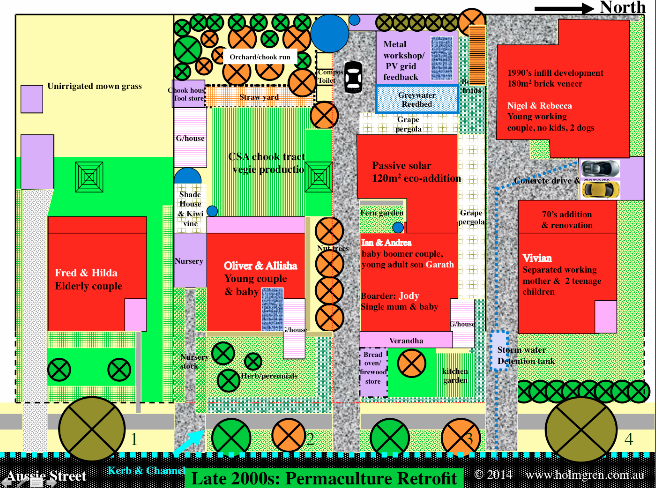

One area that has provided me a lot of inspiration is permaculture. While I’ve had a vague notion of what it is about for a number of years, it wasn’t until I read David Holmgren’s tome RetroSuburbia: A downshifter’s guide to a resilient future that I really started to take permaculture seriously. In it, he presents a vision of retro-fitting Australia’s low-density housing landscape to meet more of the occupants’ needs at home and within local communities, while consuming vastly less energy.

He’s under no delusion that enough people following this path will snowball to “solve” climate change, but is instead presenting a “prosperous way down” for those who recognise it. In doing so, they’ll be developing skills and knowledge that will be in great need during the times ahead. When future crises hit, desperate people will be looking for new ideas. Already we are seeing this, with a huge surge of interest in home food production following the mass realisation during COVID-19 that expecting the supermarket shelves to always be full doesn’t feel terribly resilient in the face of a crisis.

Permaculture is often associated with having a veggie garden, or designing houses to maximise thermal efficiency, but it’s really a mindset that can be applied to anything. I like Meg McGowan’s definition:

“Permaculture is an ethically based pattern for designing evolving systems that increase ecological health while providing for human needs.”

Another book which had a big impact on my thinking was Climate: A New Story by Charles Eisenstein. I reviewed it last year. In the book, Eisenstein makes the point that it’s not all about carbon emissions. Humans are impacting ecosystems in myriad ways, and reducing emissions alone won’t be enough to prevent ecological devastation.

To give an example: carbon accounting would say that chopping down an old-growth forest is acceptable so long as we plant another forest elsewhere to capture the same amount of carbon. But there is so much more to an old-growth forest than just the carbon it holds: the homes it provides to animals, the role it plays in preventing soil erosion and flooding, and the complex ecological relationships it fosters, developed over centuries. These things are just as essential for the continuation of life on this planet.

I’ve also been learning quite a bit about agriculture, which has a massive effect on ecosystems. Everybody has a stake in this, because we all need to eat. Over centuries, large swaths of forest have been cleared for farmland, and that continues today. The dominant industrial form of agriculture is responsible for biodiversity loss, soil erosion and pollution. Not to mention that it’s heavily reliant on fossil fuels to keep producing yields. Approaches like regenerative agriculture aim to foster living soils and increase the health of the land, rather than viewing it as an inert substrate for monoculture food production.

The way we eat represents our most profound engagement with the natural world. Daily, our eating turns nature into culture, transforming the body of the world into our bodies and minds.

The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan

Perspective

Human’s aren’t separate from nature. We are nature. Currently, we’ve got ourselves into a situation where we are completely out of balance with the ecosystems that we depend on. In the longer term, a new equilibrium is inevitable – whether that’s finding ways to live in harmony with the earth that supports us, or else consuming so much that we destroy ourselves completely, taking many other species along with us.

That sounds pretty dour, but I find zooming out a bit to be helpful. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago, and modern humans appeared around 200,000 years ago. If the history of Earth were a 24 hour day, we popped up in the last 4 seconds. Everything is impermanent – one day you, I, everything and everyone we’ve ever known will cease to exist in their current forms. On that level, it really doesn’t matter whether we “solve” climate change or not.

I am not making the argument that it’s OK to do whatever you want, even if it causes great suffering for other beings. Personally, I feel there is a lot of purpose in trying to live in a way that has a positive impact on others, both human and non-human. What I am saying is that I think it’s helpful to let go of any attachment to a particular outcome. I can try to live in a way that feels in balance, and this can be meaningful regardless of whether or not the worst predictions of the future actually come to pass.

So where does this leave me personally?

I’ve expressed quite a bit of scepticism about technology in this article. This raises some fairly existential questions for me as somebody who makes a living from writing software.

Where I’ve ended up at the moment is that while I am not a techno-optimist, I do still think there’s a role for a bit of appropriate technology in our lives. But I’m being more inquisitive about the role it plays and its wider implications. There are plenty of people working on projects to “fight” climate change or “fix” poverty, and I am viewing these things in a more sceptical light. Climate change and poverty are symptoms of a deeper problem.

I feel that it’s insufficient to say, “I’m a software developer, so I don’t need to know anything about the land I depend on for food and shelter”. I do believe that we won’t fundamentally change anything without re-establishing our connection to land and the non-human world.

For various reasons, I’ve lived in lots of different places during my adult life. I now have a strong desire to be somewhere. To really get to know the land I live on and the communities (both human and non-human) that I live within. I want my food to come from my garden, or from people whose names I know, or to be foraged from the local area. I’ll probably keep writing software for now, but I’d like it to become just one of the ways I meet my needs, rather than the only way. And I’m prioritising learning real, tangible skills: how to grow food, make things, repair things, and generally be less dependent on the monetary economy.

Resources

If you want to dig deeper, in addition to the books and articles mentioned above, here are some other resources that have shaped my thinking around this topic:

- The End Of The World As We Know It was written by Tim Hollo in the context of the worst bushfires Australia has ever seen, only 4 months ago.

I would argue that, at this point, continuing to work for climate action by demanding that governments and corporations act within the current system is both destined to fail and underplays our hand. While, of course, the urgency is such that we must keep constant pressure on all actors, our strategic goals should reach far beyond such pressure and into cultivating the new democratic systems, norms and institutions we need in order to survive and thrive.

[…]

It’s time we acknowledged that this hasn’t worked, and won’t work. The governments themselves aren’t the real problem. If we replace the people in the seats, little will change. The problem lies in a system designed as anti-ecological.

- Facing Extinction is Catherine Ingram’s long, sombre reflection on, well, facing extinction.

- Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy is an influential paper by Jem Bendall essentially arguing that near-term collapse of society is probably already inevitable, and so the time has come to discuss how we adapt to that reality. I find it helpful to consider this perspective, but it should be noted that it’s unsurprisingly quite controversial.

- A bit of an antidote to the above, The Long Road Down: Decline and the Deindustrial Future looks at previous instances of civilisational collapse and calls out that there is a large possibility space in between techno-utopia and total apocalypse, and that the road to where we’re going probably extends over several lifetimes.

Both the progressivist myth and the separativist myth have powerful emotional appeal; that’s why they’re popular. The myth of perpetual progress comforts those people who have made their peace with society as it is, and who want to believe that their lives are part of a process which leads eventually to better things. The myth of imminent apocalypse comforts those people who cannot accept society as it is, and want to believe in a catastrophe that topples the proud towers of a civilization they loathe. Still, the fact that a belief is emotionally powerful and comforting doesn’t make it true.

- The Big Picture is another insightful, zoomed-out look at where it’s all going.

- Creatures of Place is a beautiful short film looking at the life of a family living according to permaculture principles.

- Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save The World by Tyson Yunkaporta brings an aboriginal perspective to lots of topics, including the ecological crisis.