In this time of impending economic and ecological crises, we urgently need to aim for a sustainable or ‘steady state’ economy. In order to get there, we will need to adopt a ‘systems-thinking’ outlook taking into account the interconnections of our complex world. We will also need to consider the issue of de-growth, and re-prioritise kindness and the commons. We have a choice as to whether we act now to make this transition voluntarily and with fairness, or have it forced upon us by times of economic, resource and ecological collapse.

In short, we’ve got some systems thinking to do.

On Systems-Thinking

In the big picture, all things are interrelated. A virus hitches a ride on a droplet and a few weeks later the skies are empty of aircraft, you can stroll down the middle of the highway and there’s been a run on bog-roll. Anticipating these interrelationships merely requires perspective, but in our modern society, few folk have the time to indulge in such long-view observations. We have become increasingly specialised and lost the big picture perspective in inverse proportion.

We call people ‘experts’ when they’ve reached the pointy end of any discipline. However, there is often very little engagement between separate expert ‘siloes’. As we listen to them we must remember that outside of their expertise, they are no more likely to be correct than anyone else. They, in turn rely on ‘experts’ in other disciplines, even though they may hold knowledge that renders that ‘other discipline’ pontificator, wrong. This specialisation of knowledge can get whole societies into serious trouble.

Luckily there are people who travel in the opposite direction; towards an ever-bigger picture. They are Systems thinkers, or as Buckminster Fuller once put it; Generalists. Now seems like an opportune time to bring systems-thinking to the fore; to support more Generalism; and ultimately, to question what we are doing, whether we are doing well or badly, and whether we can continue on our present course.

Systems are everywhere. Your car is one such and it is made up of myriad smaller systems; oil-pumping, fuel-delivery, water-cooling, braking. If any of the smaller systems fail, the big one ceases to function as it did, despite all the other onboard systems still being intact.

On Feedback loops

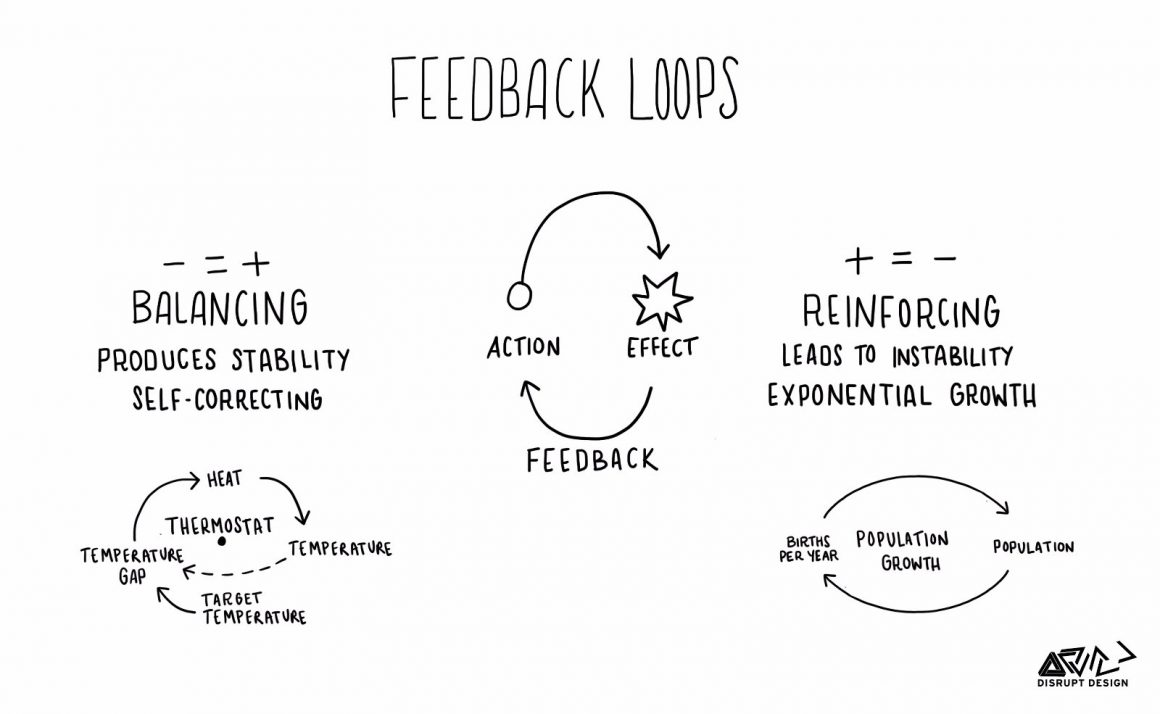

In between systems, there are feed-back loops; your engine starts off cold, so the thermostat closes off the flow of water through it. As the engine warms, the thermostat opens. Hotter still, the radiator-cooling fan kicks in. All designed to keep the cooling system in balance.

Feed-back loops can be disruptive; a nail lying on the verge flicks between your treads, penetrates the tyre and you’re on the side of the road, wheel-brace in hand, contemplating an unscheduled visit to the tyre shop.

Feed-back loops can cease suddenly; a vehicle’s many systems can be toiling away nobly, then a head-on smash results in permanent (and totally unexpected) cessation.

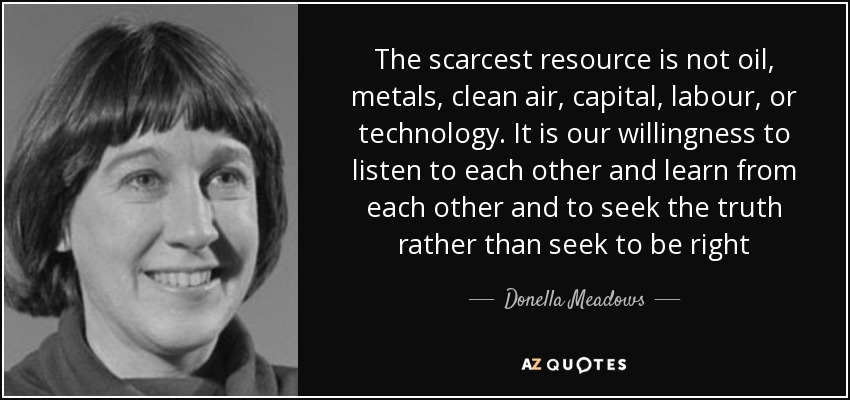

Feed-back loops can also reverse, as my favourite Systems-thinker, the late Donella (Dana) Meadows, explains perfectly here. Meadows uses the example of fish-stocks collapsing once overfished beyond their ability to procreate and replenish naturally.

Limits To Growth

Systems-thinking identifies the drivers and the driven. The knock-ons and the knock-backs. The underpinnings, the impediments and the trends. Stand back far enough and we can capture economic activity, population counts, resource stocks, rates of depletion and amounts of pollution, all intermeshed.

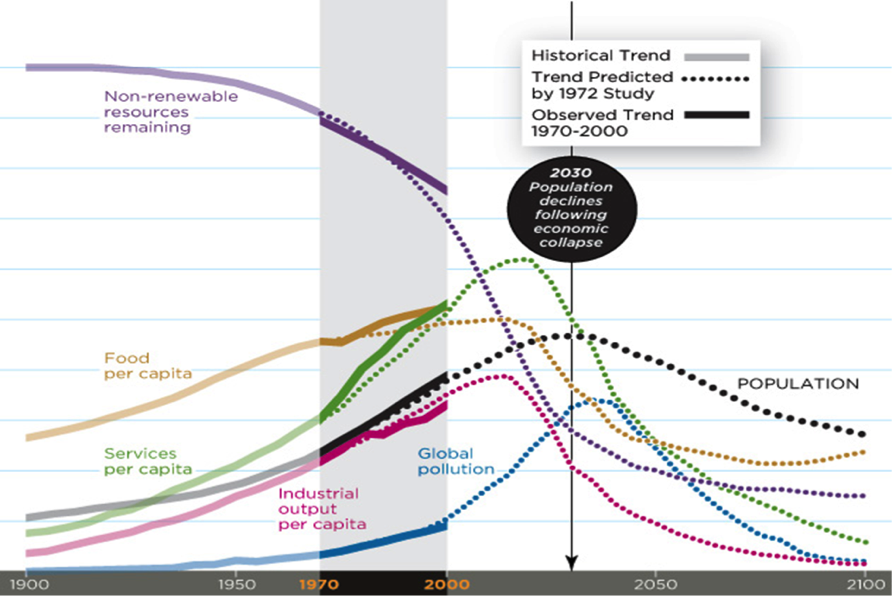

Meadows was one of the key players in the most ground-breaking Systems publication of all time; the 1972 book ‘Limits to Growth’. With hindsight, we can see what it warned of, why certain interest groups belittled its message, and crucially, where we are now on the global trajectory.

Take the time to ingest that graph. Follow every line. Note where we are, and how much we’ve done about it with fifty years of this knowledge. The resistance, of course, came from those with something to lose and from those peddling a narrative that would be rendered false by any acknowledgement of limits to eternal economic growth.

A False Narrative

That graph raises some questions, the biggest being: Why aren’t we discussing this, front-and-centre of our social narrative?

The reason is that we have largely consigned discussion and decision-making on these matters to the fictional creation we term ‘The Economy’ and its resident experts – ‘The Economists’. The assumptions of both have, until recently, gone largely unchallenged by most politicians and commentators. As a result, we have failed to challenge the assumed ‘givens’ of ‘Growth’ (often conflated with the crude measure of GDP). These ‘givens’ include poverty, jobs, income, wealth, savings, investments, consumers and a host of other. All are discussed without thought as to how they might fit into the inconvenient reality of the limits to growth seen in the above graph.

Then we have a whole lot of real counts – resource-stocks, depletion-rates, degradation and pollution – which we group under the heading of ‘The Environment’; somehow of secondary importance. The narrative – that economics trumps ecology – is false. Our weighting is incorrect and beginning to show up at global scale in the likes of Climate Change. However, the denial of human Climate impacts, often comes from the same quarters as those ridiculing the Limits to Growth problem.

Towards a true narrative

One group who straddle the two Systems are Ecological Economists , a further subset of whom examine the Energy system. Some Energy-only experts have back-thought their realisations and begun challenging the Economics-only experts. A select few such as Nate Hagens have tied it all together.

Our Big-Picture System; Resources and Natural Capital.

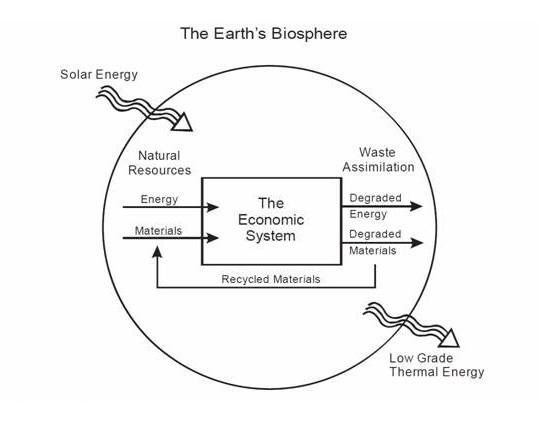

In rough terms, we extract, process, consume and excrete natural resources. Think of it as a one-way conveyor-belt. Economics is the measure of the speed of the conveyor and how much stuff is on it. The remaining stocks at the front and the pile of poo behind go unmeasured in direct terms. The exception is when they show up indirectly. For example, the smell might show up as reduced house-prices near landfills, or bushfire cleanups may emerge as an inconvenient cost.

When we started this industrialisation process 200 years ago, the resource stocks of the planet were largely intact. We have increased the volume we are extracting/excreting and the speed at which we are doing it, ever since.

Resources fall into three categories; two being extracted, and one being filled.

- Finite resources – These we can dig up, use and – in theory – recycle. Obviously, there are two limits there; the amount available and the recycling possible.

- Renewable resources – These are the depletable resources like fish-stocks and soil-nutrient. Obviously, we have to use these at less than the renewal-rate.

- Sinks – These are the capacity of the systems of the biosphere – the atmosphere, land and ocean – to absorb our outputs and render them inert.

Renewables can be used to substitute for finite resources, but only at a rate no faster than they renew. Thus, in theory we can use solar energy (and the solar derivatives wind and hydro) to displace the finite stock of fossilised sunlight we currently use. Further complications arise, though, when other finite resources are required, in ever-increasing amounts, to create that solar-energy infrastructure. A classic example is the lithium and rare earth metals needed to produce solar panels and storage batteries.

Energy, diminishing returns and ‘EROEI‘

Economists tell us that energy represents a few percent of ‘the Economy’. They are wrong. Without energy nothing – absolutely nothing – happens. Including life, incidentally. So energy it is the 100% underwrite; the linch-pin of all linch-pins. Which makes it quite important when we’re Systems-thinking.

At the beginning of this 200-year aberration, we thought of energy as human, animal, and a small amount of wind and water. Productivity was therefore thought of as output per person (or horse). Nowadays, labour accounts for less than 1% of the work-done globally, most of the 99% is done by fossil-fuel energy.

There are thermodynamic limits to how well we can use fossil energy. As we approach these limits – despite new efficiencies such as computer-control, fuel-injection, metallurgy and design – their increase in ‘productivity’ will naturally be tailing off. This inexorable tailing-off of ‘productivity’ seems to be a puzzle to economists; that’s what happens when you concentrate on 1% of the big picture…

But it gets worse. As we hoed into the one-off stock of fossilised sunlight – coal, oil and gas – we went for the best, first. The lightest, sweetest, closest to the surface, closest to home, most pressurized oil. The blackest coal, the gas closest to shore, to a terminal or pipeline. The source with the least environmental safeguards and/or the most repressed workforce, and so on. This means that all ‘next’ options are ‘worse’. We have burnt the best – it’s gone. We are now down to fracking, tar-sands, and deep-offshore sources of oil. We’ve even contemplated lignite!

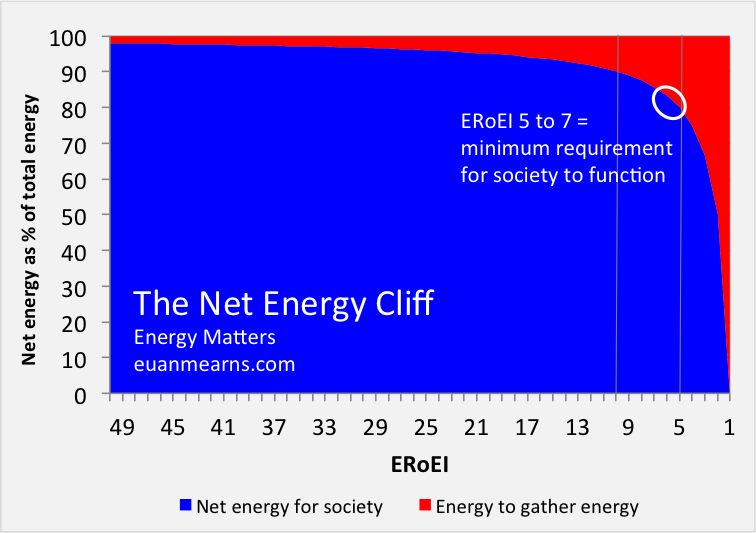

The problem is one of a reducing energy return on our energy investment (a reducing EROEI). All life has to be in positive-EROEI territory, the classic example being a wolf chasing a rabbit; if the rabbit is scrawny and expends energy in the life-or-death chase, the eating of it may not return the energy the wolf expended doing the chasing. There may be a thousand rabbits of similar plumpness a similar distance away, but if the wolf doesn’t up his EROEI game, he’ll die.

We have gone for the best EROEI energy options at every move. Until we used the best and started down through the remaining options. Oil, at it’s best, had an EROEI of 100:1; for every barrel of oil it took to extract oil, we got 100 barrels out of the ground. Globally, that is now well under 20:1 and dropping like a stone.

We will likely compensate at first by skimping on infrastructure maintenance, then by increasingly desperate triage. If that sounds totally at odds with politicians urging ever-more roads-to-nowhere, well, it is.

The same reduction in resource quality noted for fossil energy is true of all other resources. Copper now requires the removal of 400 tons of overburden, where it once required 10. Not only that, but the diggers are running on 20:1 EROEI energy, and dropping.

In summary, we don’t recycle enough and we don’t sequester carbon enough, because both demand more energy than we can spare, and the divergence is widening. In the small circles discussing these compounding issues, it has become known as the Red Queen syndrome; you find yourself running ever faster just to stay on the same spot.

Where to from here?

Logic tells us that what we have been doing, is creating our problems. It suggests, then, that we need to be doing something other than what we’ve been doing. Logic also tells us that we will end up living at a sustainable level, whether we choose to go there proactively or whether we are forced there by our own resource-depletion and habitat-destruction efforts.

To be as smooth as possible, this change has to be managed using a Systems overview. Single-topic approaches, at this stage, cannot be adequate – our approach needs to consider the big picture and have all the above factors weighted correctly. This is quite a task in the remaining time available, and considering the predictable push-back.

We could start by introducing clearer rules around use of the three Resources. How about:

- No use of finite resources unless either, a. the energy to recycle them, or b. their complete replacement by renewables are both proven and feasible.

- No use of renewables (eg soil) at beyond their capacity to renew; the cost of monitoring to be borne by the user.

- No filling of sinks (eg pumping carbon into the atmosphere) beyond agreed levels; the cost of monitoring to be borne by the user. (It may be that ‘cost’ is not effective enough and we have to revert to forced cessation).

How we fit our social construct into this new approach is up for grabs. I suggest that less people equals more resources per head; this ratio being the true measure of wealth. Economics seems to have the wrong end of the stick yet again. Would you rather have fuel in your tank and food on the table, or a collection of bank-issued digital ‘1’s and ‘0’s? Ascertaining the resources-per-head desired – globally but within New Zealand too – will suggest an optimum population. As Glenn Banks of Massey University suggests, we need to focus on increased consumption as much as population growth. Again, going there voluntarily, and at our own pace, rather than being forced by circumstance, would seem preferable.

The Steady State Economy

Ultimately, we must construct a Steady State economy based on the above principles. In other words, we have to reverse growth, abolish interest and reduce debt, and reflect limits by setting limits and enforcing them Other societies have, for good reason, taken such steps. Just how de-growth fits with big-picture Systems thinking is an interesting intellectual aside, but the hard reality is that in the coming decades, we will likely be consuming less. Far less.

So what will the Steady State societies of the future look like? Likely we will be attempting 100% recycling/reuse of materials. Likely we will be attempting 100% nutrient recycling in food terms. Likely we will be valuing biodiversity far more. Likely we will have a discussion about ‘the Commons’, and reclaiming them (from those who ‘enclosed’ or privatised, monopolised, then charged). Likely we will be more local. A lot more local. Likely we will become a more egalitarian, more community-minded and ‘trust-based’ society. Maybe we will even become more kind.

Time we got the change underway.

Further reading:

- Thinking in Systems – Donella Meadows,

- Limits to Growth (and updates) – Meadows et al,

- Overshoot – William Catton,

- Short History of Progress – Ronald Wright,

- The Long Emergency – James Kunstler,

- Doughnut Economics – Kate Raworth

Help us develop the new narrative for a Steady State Society”

Please comment on this article in the ScoopCitizen member comment section below:

Learn more or get involved by signing in to ScoopCitizen in the comments or the Survey window below

This survey is A ScoopCitizen Engagement on the 2020 Budget. You must log in to participate. Access is free to all citizens.

ScoopCitizen: An Engaged Journalism Community

A new community for pro-democracy engaged journalism

Help us make sense of our shared future narrative through in-depth public interest journalism on The Dig.

Add your voice and drive change

Our pro-democracy Civic journalism approach allows you to learn about and participate in the journalistic and civic discourse on issues that matter to our communities.

We want your input in developing our investigation of this important issue.

It is completely free to join and takes just a few seconds via email, or social media account via our tech partner NextElection.

Learn more or get involved by signing in to ScoopCitizen above.

Who are ScoopCitizens?

ScoopCitizen is a membership-based Engaged journalism service supported by the Scoop Foundation for Public Interest Journalism. Find out more here>>.

Supporters and sponsors are welcome in this endeavour to chart a course for our interconnected post-crisis world.