Jeremy Rose analyses the social welfare policies of Ardern’s Labour-led Government and other prospective parties.

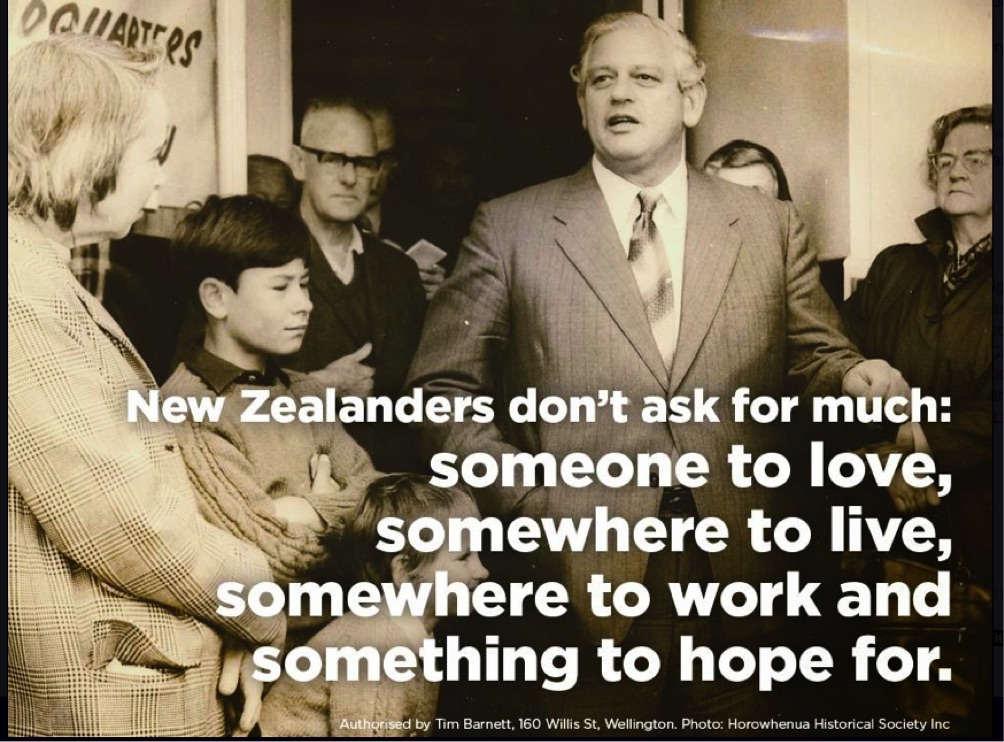

Jacinda Ardern launched Labour’s 2017 campaign by quoting former Labour prime minister Norman Kirk as saying: “People don’t want much, just someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work, and something to hope for.”

Inspiring words that will have given hope to the country’s poorest – those struggling to survive on benefits – that things would change for the better if the Labour Party won the election.

So how do the records of third and sixth Labour governments compare when it comes to benefits?

When the Kirk government came to power in 1972 the unemployment benefit was $17.10 a week or in today’s terms, adjusted for wage inflation, $344. Three years later the benefit had increased to $30.75 a week or the equivalent of $402 today.

By comparison when the current government came to power three years ago the unemployment benefit was just $237.37 and it remained at that level until earlier this year when it was bumped up by $25 (or $1.91 in 1975 dollars)

A Living Allowance

The third Labour government’s benefit increases were informed by a 1969 Royal Commission into the social security system established by its National predecessor. The commission, chaired by Justice Thaddeus McCarthy, said, among other things:

- The community is responsible for giving dependent people a standard of living consistent with human dignity and approaching that enjoyed by the majority, irrespective of the cause of dependency…

- Need, and the degree of need should be the primary test and criterion of the help given by the community irrespective of what contributions are made.

- Coverage should be comprehensive irrespective of cause wherever need exists.

And that cross-party consensus, setting benefits at a level enabling recipients to participate in society and live with dignity held until Jim Bolger and Ruth Richardson’s ‘mother of all budgets’ in 1991 which slashed the unemployment and sickness benefits while leaving super untouched.

The Undeserving Poor

Economist Brian Easton, in his recently published economic history of New Zealand, Not in Narrow Seas, says the shift saw the government: “targeting absolute rather than relative poverty and categorising those in need as either ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’.”

A new political consensus was born. Having condemned the cuts in opposition, the Labour-led government that came to power in 1999 failed to restore benefit levels during its nine years in government.

Benefit levels (excluding Super) were pegged to the CPI – not wage inflation. Wages grow at a faster rate than the consumer price index (the official measure of inflation) and the CPI tends to be lower still than the inflation experienced by those on low incomes.

Rising Inequality

Stats NZ has calculated that for beneficiaries the cost of living over the 11 years from September 2008 to September 2019 rose by 1.9 percent a year compared to 1.6 percent across all households.

With each passing year the country’s poorest slipped ever further behind those in work.

In 2016 the National Government increased benefits by $25 for families on welfare – the first increase in decades.

Research commissioned by the Salvation Army earlier this year found that current benefit levels were about 25 percent lower in real terms when compared to where they were in the aftermath of the mother of all budgets.

As we’ve heard, the current Labour-led coalition again increased benefits by $25, earlier this year, as well as linking future automatic increases to wage inflation rather than the CPI.

The government also introduced a “best start” payment of $60 a week for the first three years of a child’s life, increased the accommodation allowance, and doubled the winter energy payment.

During the election campaign the Labour Party has repeatedly claimed that sole parents are better off by more than $100 a week as a result of the changes.

In figures supplied to Child Poverty Action by the Ministry of Social Development the average increase was shown to be $101. But an initial analysis by CPA spokesperson economist Susan St John found that the real weekly increase for a sole parent with two children (over the age of 3) was about $48 – or $5 per person per year since 2017.

By the Salvation Army’s calculation, sole parents would need about $50 extra a week simply to get back to where they were following the Bolger government’s historic slashing of benefits in 1991.

Linking future increases to wage inflation will make a difference over time – but in the short term it will be barely perceptible with wage increases likely to be negligible in the age of COVID-19.

An increase… for some

The current right-of-centre Government in Australia temporarily doubled benefit levels in anticipation of the wave of unemployment resulting from the pandemic.

On this side of the ditch, the government introduced a temporary COVID Income Relief payment of $490 a week for those made redundant – a tacit acknowledgement that current benefit levels are woefully inadequate.

But as we’ve already heard, someone on the job seeker allowance received an increase of just $25 – increasing their payment to $250 a week. .

If there was a glimmer of hope for beneficiaries during this government’s term, it was the setting up of the Welfare Expert Advisory Group and its subsequent report.

Predictably, the group found current benefit levels failed miserably when it came to providing enough for a “minimal level of meaningful participation in their communities.”

A single person receiving the benefit and renting privately would need between $130 and $170 a week more to reach that threshold. A couple with two kids would need something like $350 more a week to participate meaningfully in their communities.

And increases of between $50 and $230 a week were required for beneficiaries to reach the much lower threshold of having “the basic necessities of life.”

It’s worth noting that it costs more than $300 a day to keep someone in prison. The conveyer belt from poverty to prison just keeps on keeping on.

“Shovel ready” Beneficiary Parents

A recent NZIER study found increasing benefits would be good for the economy. The paper, commissioned by a coalition of social service organisations, found that: “For New Zealand an increase in transfer payments such as social protection expenditure of 1 percent of GDP raises GDP by about 1.53 percent after one quarter.”

Despite findings like that one, affordability remains the most common argument for not raising benefit levels. WEAG’s recommendations come with a price tag of $5.2 billion per annum.

But as economist Geoff Bertram pointed out in a letter to the Dominion Post, money isn’t always an obstacle. “Tens of billions are to be directed at the “shovel ready” Think Big projects that corporate lobbyists always push. Beneficiary parents are “shovel ready” to give their kids a decent meal tonight. They just don’t have powerful lobbyists in their corner.”

In a paper published last year, titled, National’s Family Support Policy: A New Paradigm Shift Or More The Same?, Susan St John and Gerard Cotterell argue that the “targeted stigmatising approach” towards beneficiaries ushered in with the mother of all budgets remains entrenched under the current government.

“The 1970s consensus that the welfare state was about ‘participation and belonging’ and ‘community responsibility’,” they wrote “was replaced by values of ‘welfare only for the poor’ and self-responsibility’.’”

That inability of beneficiaries to participate in society was painfully brought home to me while researching this article. I’d hoped to include a Zoom panel discussion with two or three beneficiaries talking about what’s on offer from the political parties this year.

A mother of three in Auckland was keen at first but had two concerns: the first a practical one – she has limited access to the internet and with cerebral palsy getting out to the library can be difficult. The second was even more worrying, she feared that speaking out publicly could make her life difficult with her case manager.

She told me her cerebral palsy entitled her to an extra $9 a fortnight but that was more than eaten up by the $20 taken from her each fortnight to pay back hardship loans.

The hardest thing about trying to survive on the benefit: “My kids desperately wanted to play soccer but I couldn’t afford the boots or the fees. Because of my condition I can’t take them outside much.”

Another sole parent, who also feared that speaking on the record could make her life difficult with WINZ, told me there needed to be a paradigm shift in how beneficiaries are viewed.

She had spent years volunteering at her daughter’s school – unpaid work but work nevertheless. “Why not pay sole parents for the voluntary work they do?,” she asked. “Or at least recognise the work by giving us enough to survive with some dignity.”

Of the parties likely to be in parliament, on current polling, following the election only the Greens are challenging the “targeted stigmatising approach” introduced back in 1991 with the mother of all budgets.

The Maori Party, TOP and Social Credit all have policies significantly more generous to those on benefits.

We will be working on expanding this conversation. We hope to host an online panel discussion before the election and will keep following the issue beyond the election.

What the parties are offering:

Labour

Re-instating the Training Incentive Allowance. Sole parents will be eligible to up to $112.89 a week to study higher skills causes.

Increasing the abatement level from $90 to $160 a week. This is the first change to the level people on benefits can earn before the state begins to claw them back since 1986. It’s long overdue but in real terms still leaves beneficiaries worse off than were post the mother of all budgets when the inflation adjusted rate was $184.)

Flexiwage – An employer subsidy of up to $3500 for each unemployed worker taking up a job.

National

No change and a commitment not to cut benefits any further.

Bring back sanction to mothers who don’t name the father of their child.

$4000 to tertiary institutions that successfully re-train someone into a new job.

Greens

The Greens are one of the few parties offering a complete shake-up of the benefit system.

A guaranteed minimum income of $325 a week to anyone not in work (including students.)

Sole parents will receive a minimum of $435 a week.

A universal payment of $100 per child under three.

NZ First

Carry out a review of the practicality of bringing back a universal child benefit for children under 16.

ACT

ACT leader David Seymour has promised to reverse Labour’s benefit increase of $25 a week.

End the Winter Energy Allowance payment policy

Control what benefits can be spent on with what sounds a lot like electronic “food stamps”.

Maori Party

Double all working-age benefits.

Increase the abatement level for those earning income while on benefits

TOP

Universal Basic Income of $250 a week. (And a flat tax of 30 percent.)

TOP leader Geoff Simmons said in a debate with Max Rashbrooke that the trade-off between a UBI and a guaranteed income, like that being promoted by the Greens, was “good incentives vs adequacy”. You can have one but not the other. A benefit system inevitably ends up with marginal tax rates that disincentive working. He said under TOP’s proposal no-one would be worse off and most would be better off.

Social Credit

Unemployment benefit raised to $400

Sole parent allowance raised to $470

Two adult and child benefit raised to $580

Panel Discussion Video and Engagement

Watch the video featuring our knowledgeable and passionate panelists and take part in the discussion below via a ScoopCitizen survey:

Benefits Engagement Survey

1. Do you support WEAG’s call for an immediate increase in benefit levels of between 12 and 47 percent?

2. NZ First and Social Credit are both proposing a return of the universal child benefit. Does the idea have merit?

3 Do you agree that the community is responsible for giving dependent people a standard of living consistent with human dignity and approaching that enjoyed by the majority, irrespective of the cause of dependency.

4. Should the incoming government consider adopting an MMT-style job guarantee?

A Job Guarantee – is an open-ended public employment program that offers a job at a living (minimum) wage to anyone who wants to work but cannot find employment.

5. Should the incoming government investigate the viability of a guaranteed basic income as outlined by TOP?

6. What other innovative solutions could we explore to provide for those unable to support themselves financially?